Scholars are busy attempting to predict the effects of climate change, including how it might harm people in some parts of the globe more than others. A recent report by The Pacific Institute, sent in by Aneesa D., does a more fine-grained analysis, showing which Californians will be the most harmed by climate change.

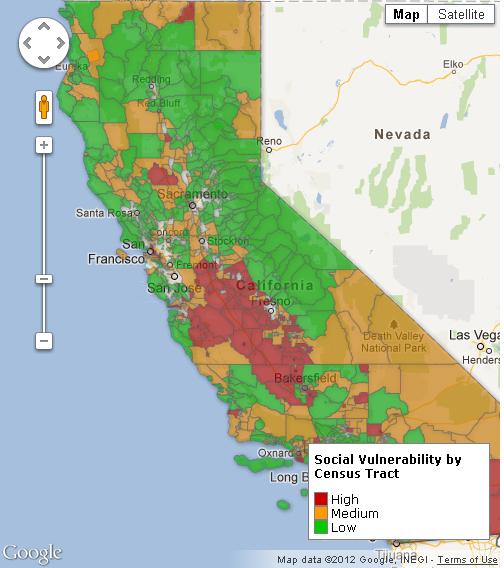

They use a variety of measures for each Census tract to make a Vulnerability Index, including natural factors (like tree cover), demographic factors (like age), and economic factors (like income). At the interactive map, you can see the details for each Census tract. Their compiled index looks like this:

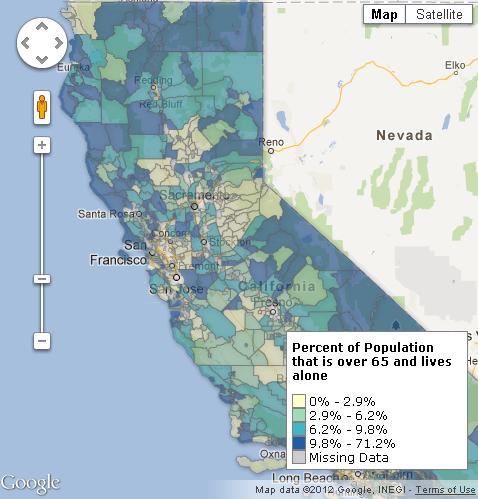

You can also see the Vulnerability Index for each measure individually. Here is the data for the percent of people over age 65 who live alone, a variable we know increases the risk of death from heat wave.

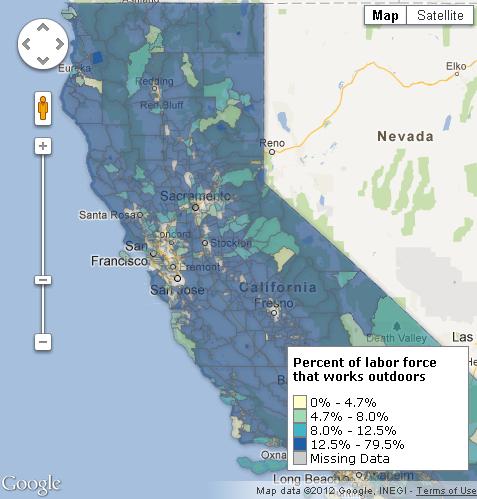

And here’s the data for the percent of workers who labor outside:

There’s lots more data at the site, but what’s interesting here is that, even in incredibly wealthy parts of the world, climate change is going to have uneven effects. When it does, the most vulnerable people in the more vulnerable parts of the state are going to migrate to the other parts. Most Californians don’t imagine that their cities will be home to refugees, but this is exactly what will happen as parts of California become increasingly difficult to live in.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.