While the news often discusses the proportion of the population that is unemployed, sociologists also talk about the working poor (people with full time jobs, but who are paid so little that they remain below the poverty line) and the underemployed (e.g., people who have part-time jobs, but wish they were full-time).

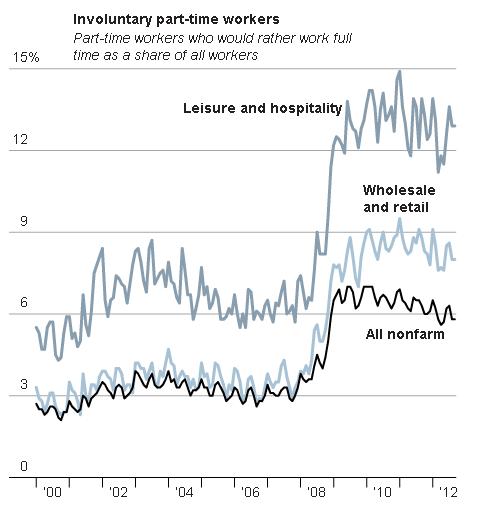

The New York Times recently put together a graphic illustrating the rise of underemployment due to the recession. Overall, the number of people who are working part-time involuntarily has risen. In the related article, reporter Steven Greenhouse quotes a retail consultant explaining: “Over the past two decades, many major retailers went from a quotient of 70 to 80 percent full-time to at least 70 percent part-time across the industry.” Underemployment has risen in some economic sectors more than others, notably leisure/hospitality and wholesale/retail:

Among other employers, Greenhouse profiles a Fresh & Easy store in San Diego. Employed there are 5 full-time managers and 17 part-time workers. Shannon Hardin, who has worked there for five years, averages 28 hours a week and earns $10.90 an hour.

Workers like Hardin often get very short shifts (designed to increase the number of employees in the store only during rush times), irregular schedules (making it difficult to arrange childcare), and last minute requests to work. Being inflexible can get an employee fired.

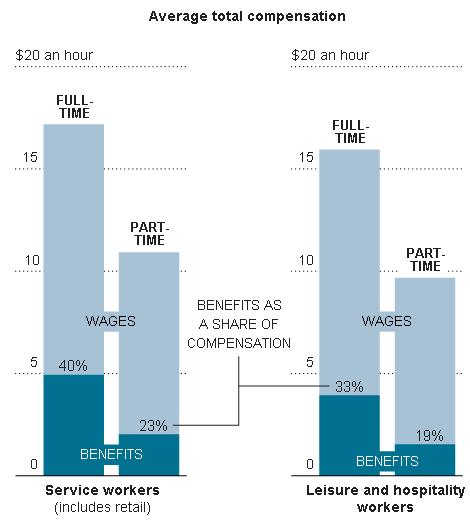

This is why employers like part-timers; from the company’s perspective, they’re cheap and flexible:

From the employee’s perspective, of course, it means a meager existence, an uncertain future, and a life led at the whims of a company’s bottom line.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.