Dmitriy T.M. sent along a Slate slideshow chock full of interesting information on cigarettes and health warnings internationally. I found this particular tidbit most compelling:

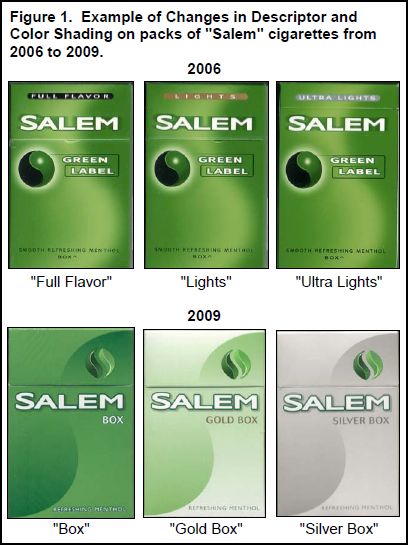

As of June 22, 2010, U.S. cigarette manufacturers are no longer allowed to use the words “light,” “low,” and “mild” to describe their product because it gives the false impression that these cigarettes are better for you than others (source). In place of the words, however, manufacturers are using light and dark colors. Between 2006 and 2009, for example, Salem cigarettes phased out their packages labeled with words (top) and moved to color based differentiation (bottom):

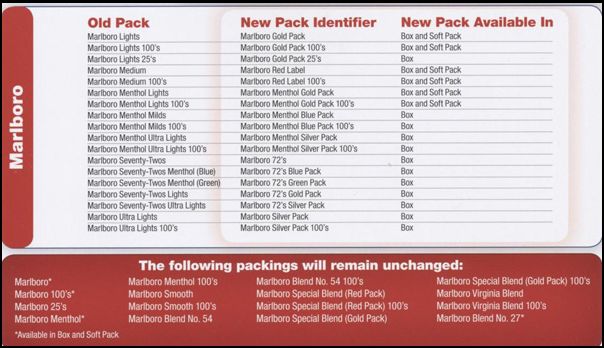

Marlboro has issued a “cheat sheet,” showing the move from descriptors to colors:

This is a very strategic move on the part of cigarette manufacturers, who know that the colors give consumers the same impression as the words. At least one study has shown as much:

Scientists at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., studied 197 smokers and 200 nonsmokers who were shown two mock cigarette packs, one light blue and one dark blue.

They were then asked, “Which one would you buy if you were trying to reduce the risks to your health?” Eighty-seven percent of those surveyed selected the lighter-shaded pack, while just 8 percent chose the darker-shaded pack.

The New York City Health Department is trying to combat this new strategy with commercials aimed at exposing it:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.