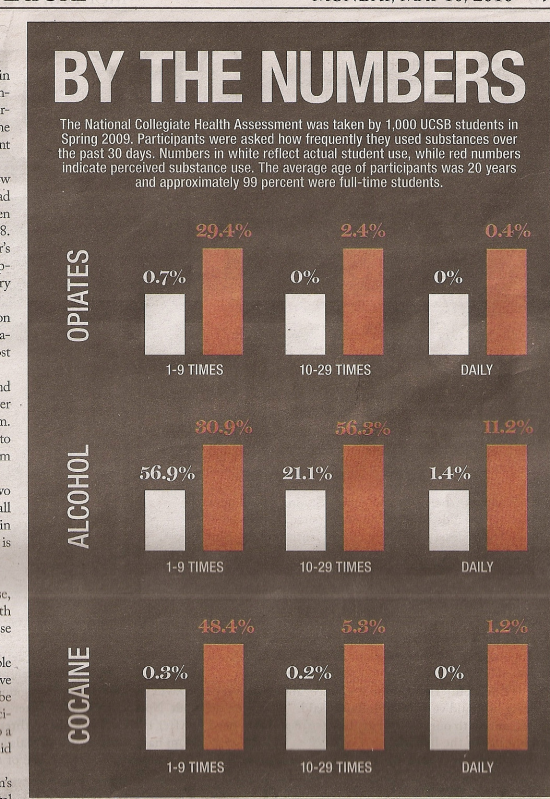

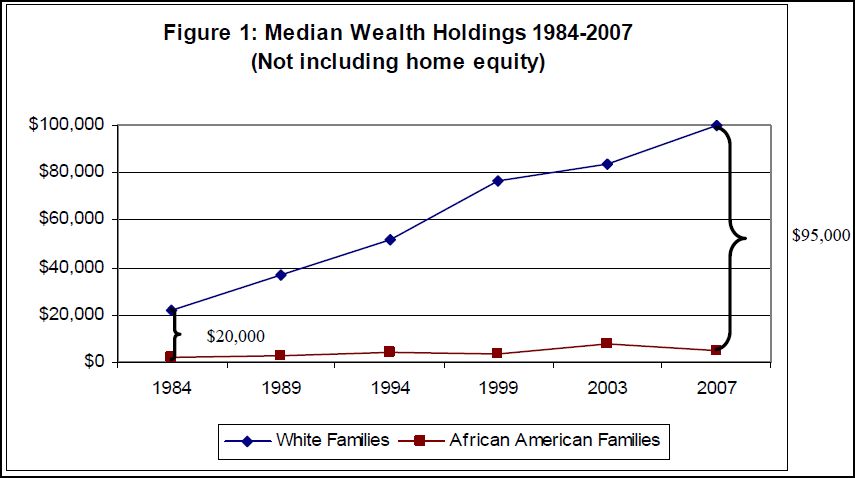

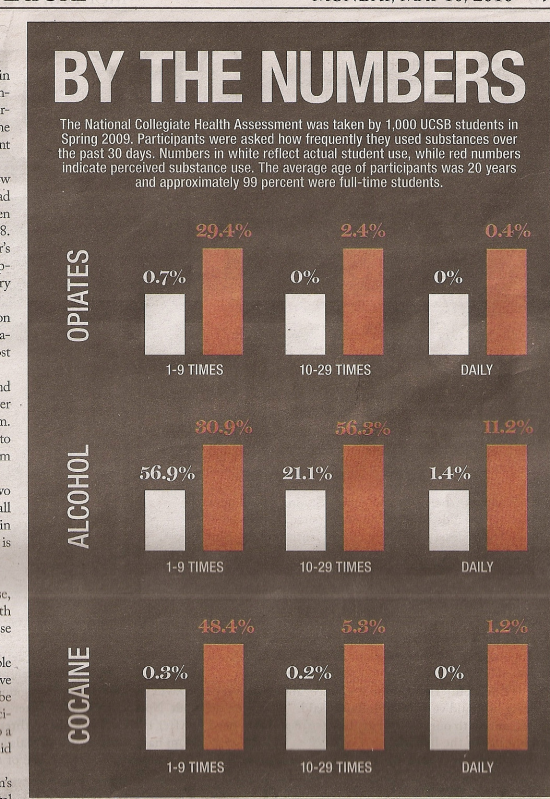

The phrase “pluralistic ignorance” refers to a situation where a large proportion of a population misunderstands reality. They may all agree, but they are, nonetheless, mistaken. This data on University of California-Santa Barbara students from the National Collegiate Health Assessment is a great illustration of this idea; it’s also a great illustration, however, of a terrible, terrible illustration.

Let’s get past the bad graphic first. The white bars (which represent the percent of people reporting that they themselves used opiates, alcohol, or cocaine) are all the same height, despite the fact, for example, that 56.9% of students reported using alcohol 1-9 times in the last month, but only 0.3% reported using cocaine. So the bars do not actually represent the percentages they are supposed to. The red bars (which represent the percent of people that respondents think are using drugs and alcohol) suffer from the same problem. In one case, the white bar should be even higher than the red bar.

But, if we can get past the poor graphic, then the information is really interesting. In all but one case, the number of people reporting drug and alcohol use is smaller than the perceptions of how many people are using these substances. For example, looking at the middle column, (almost) no one reports using opiates or cocaine 10-29 times last month, but students perceive that 2.4% and 5.3% of the population (respectively) are; similarly, 21.1% of students report drinking alcohol 10-29 times last month, but they perceive that over half the population is drinking that frequently.

This pattern is consistently true in all cases except for the percentage of people who drank alcohol 1-9 times in the last month. The majority of respondents who drink reported that they did so at that rate, but they perceive that others are drinking far more than they are. The overall impact of the illustration, then, is correct. On the whole, students perceive more drug and alcohol use than they report.

It’s possible that people are underreporting and their perceptions are more true than the self-reports. If their self-reports are more true, however, than we have a case of pluralistic ignorance. In this case, students agree that the rate of drug and alcohol use is higher than it actually is. They may, then, feel pressure to drink and do drugs more frequently to fit in, even as doing so results in just the opposite.

Eager Eyes, via Flowing Data.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.