This summer I went hiking several times in California’s Eastern Sierra. Each time I went I counted the number of male to female hikers and ended up with a 5:1 ratio. This reflects many women’s experience of the wilderness and outdoor sports such as rock climbing or mountaineering. These are male-dominated arenas.

One of the reasons for that is because these activities are advertised to women as an escape from their stressful lives, not as a sport meant to challenge their physical ability. Outdoors equipment marketed towards women, then, consistently focuses on comfort and style, in contrast to men’s marketing. Moreover, much of the gear that is produced for women assumes less of a desire to do activities that are as physically demanding as men — the gear is often less hardy and more decorative. The assumptions behind these marketing strategies reinforce stereotypical ideas of gender: that women are physically weak, that women are fascinated by fashion, that there is one specific female body type, and that women are “soft.”

Exhibit #1: Women’s backpacks

Osprey is generally acknowledged as the maker of the best backpacks for hiking and backpacking. Their top-of-the-line backpack for long multi-day backpack trips for men, the Xenith, can hold 105 L and between 60-80 lbs. The women’s pack, the Xena, on the other hand, can hold 85 L and between 50-70 lbs. This is because the women’s pack is shorter. Osprey is betting that most women have a shorter torso and thus need a shorter pack. While this might be true for some women, they could attempt to engineer another type of pack that would allow women to carry the same poundage as men. Moreover, it is unclear why these packs are labeled “men’s and women’s.” Plenty of women have longer torsos and men shorter ones. And, indeed, on backpacking forums on the internet, you constantly see stories of people buying gear of the “wrong sex” so that it actually fits.

Exhibit #2: Choose your sex!

Many hikers and backpackers buy gear online and oftentimes the structure of the websites of the major companies who sell gear reveals the companies’ assumptions about the interests of their consumers. Some, such as Arc’teryx, open their websites with gender distinctions. One must choose men’s or women’s products immediately upon going to their site. Other companies, such as REI, open their site with the opportunity to choose an activity, such as hiking, climbing, cycling, running, etc. or sex category, which is better. By so dividing their products, Arc’teryx is making it harder for those who need to buy gear from the “wrong” sex or to market unisex gear while REI is making consumers feel part of a larger community of climbers or backpackers or hikers.

Exhibit #3: Playful gear

The marketing of backpacking gear is itself highly gendered, with women’s gear being presented as comfortable and stylish. Oddly, it is not marketed with an eye towards serious wilderness excursions. Take, for example, the Yumalina pant manufactured by Mountain Hardwear. The men’s version is described as “Durable softshell seriously protects on the outside, while lightweight fleece on the inside keeps you warm on those chilly hikes” while the women’s version is described as “Serious on the outside and soft on fuzzy on the inside. Perfect for work or play during the winter.” The women’s pant is thus not seen as for someone who is serious about backpacking.

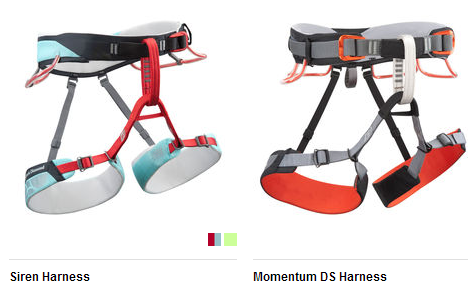

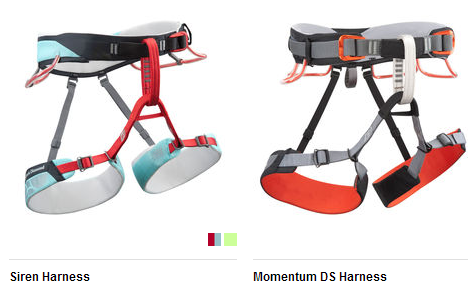

Exhibit #4: Decorative, sexy climbing

The naming and color palette of much women’s gear also reflects the idea in the backpacking industry that women needed to be treated delicately. Black Diamond, which manufactures popular rock climbing harnesses, has named their women’s harnesses “Primrose,” “Siren,” “Aura,” and “Lotus,” emphasizing the stereotypical connection between women and flowers and sexuality. Women are connected to passive agents. The harnesses themselves are typically in pastel colors as well. This is in contrast to the men’s harnesses, which are named “Chaos,” “Focus,” “Flight,” and “Momentum,” which are strikingly active words in comparison and are designed in bright, bold colors.

As Brendan Leonard points out in his post, Girly Girls and Manly Men, “No company feels like they have to do anything special to men’s gear, or ‘masculinize it’ it. Yoga is arguably maybe the most feminine (or just female-dominated) of any active pursuit, but you don’t see any companies making yoga mats with patterns on them that look like cascades of hammers or football helmets or beer mugs, to encourage men by saying, ‘It’s OK, dude. You can own one of these and still love Home Depot.’” Why do companies thus feel that women cannot be serious backpackers, hikers or climbers without feminized gear?

Cross-posted at The Huffington Post.

Adrianne Wadewitz, PhD is a Mellon Digital Scholarship Postdoctoral Fellow at Occidental College specializing in emerging media from the 18th-century to the present. Peter James is an avid outdoor photographer and wilderness traveler. You can follow them at @wadewitz and @PBJmaesPhoto.