Please welcome Guest Blogger Philip Cohen. Cohen is a sociology professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he specializes in studying the family. We are pleased to reproduce a post from his own blog, Family Inequality, about (how statistics lie and) the recent media hype about the decrease in the divorce rate.

—————————————-

Delivering some “good news for Christmas,” The National Marriage Project, under the editorship of the sociologist W. Bradford Wilcox, has released a report titled The State of Our Unions, 2009: Money and Marriage. It has a lot of useful information on marriage and families, with some editorial bending in the pro-marriage-and-family direction.

My beef here is with the chapter titled “The Great Recession’s Silver Lining?” In it, Wilcox writes:

judging by divorce trends, many couples appear to be developing a new appreciation for the economic and social support that marriage can provide in tough times. Thus, one piece of good news emerging from the last two years is that marital stability is up.

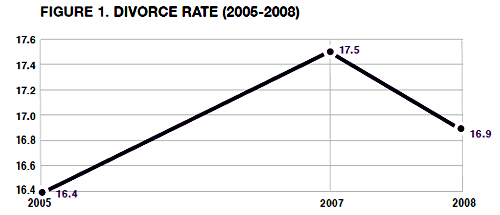

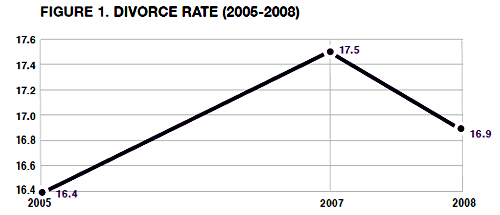

That line was quoted by Ross Douthat at the New York Times, which is a shame, because there is no evidence about anyone’s appreciation for marriage in the chapter. Instead, the evidence for this assertion is presented in a graph that shows three data points in the divorce-rate trend:

The figure shows a decline in the divorce rate from 2007 to 2008. In the press release he calls that drop “the first annual dip since 2005.” (The rate shown here is divorces in a given year per 1,000 married women in the population that year.) Couple things:

1. There is no data point for 2006, so for all we know the divorce rate actually rose higher than it was in 2007, and started falling before the recession, which officially began in December 2007.

2. Despite the dramatic turnaround apparent in this graph, it’s really not enough to go on to draw the kind of conclusion he draws.

The second point is more important, because there really is a lot of research that shows job loss increases the odds of divorce. So why should this recession be different? It’s possible it is, but there’s no evidence – in this report or elsewhere that I’ve seen – of such a change.

In fairness, Wilcox wrote a column in the Wall Street Journal that musters some anecdotal evidence for his theory. But nothing to get him this far: “For most married Americans, the Great Recession seems to be solidifying, not eroding, the marital bond.” Even if the divorce did drop a little in one year – that doesn’t say anything about “most married Americans.”

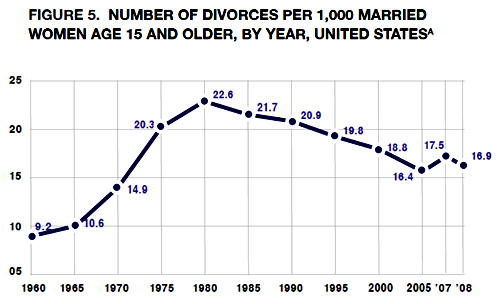

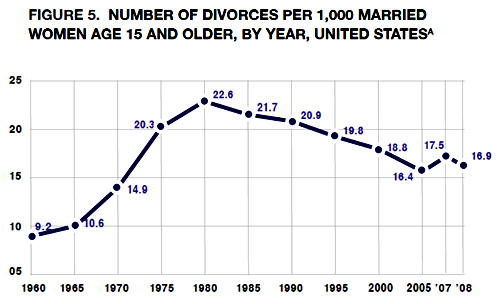

That three-point graph is especially unfortunate because it leads to interpretations like this: “The divorce rate … had previously been on an upward path, rising from 16.4 divorces per 1,000 married women in 2005 to 17.5 in 2007.” That seriously misstates the real trend in divorce rates, which have actually been falling since 1981. And there is nothing in the trend to suggest that recessions teach couples a “new appreciation for the economic and social support that marriage can provide in tough times.” In the appendix, Wilcox presents that longer trend, which makes his previous figure seem much less dramatic.

(The graph seems a little off to me – notice how 10.6 is closer to the line for 10 than 14.9 is to the line for 15 – but I’ll work from his numbers below anyway.)

I think the story of a turnaround in divorce rates has traction because, like crime, divorce is one of those things many people assume is always getting worse (I see this in student papers frequently). So any decline in divorce rates looks like an important change.

What is recession’s effect?

I previously speculated that, because this recession was costing so many men their jobs, more men were likely to be become primary caregivers, and do more housework. The downside – I speculated – was that “maybe men getting ’stuck’ with childcare doesn’t bode well for marriages.” To support that speculation, I showed a graph of divorce rates that had little upward spikes during some recent recessions. The graph was not the real evidence for the argument – which was here:

We already know that economic hard times contribute to marital instability and divorce. Studyafter study after study have found that losing a job increases the likelihood of divorce, with some evidence that husbands’ losses matter more.

Here is a new graph I made, with the “crude divorce rate” (divorces per 1,000 people in the population) in blue, superimposed over Wilcox’s calculations in red. (His takes more work, which is probably why he doesn’t have it for every year. But they track quite well, with some pulling apart some after 1980, which has to do with changes in the population composition that probably aren’t important.) I also put the recessions on there, roughly, by hand with purple bars.

Source: Divorce rates from 2010 Statistical Abstract and various prior years; business cycles from 2010 Statistical Abstract.

Two things here:

1. Over the longer run, there is no obvious relationship between recessions and the divorce rate. There are big social forces at work here (like the rise of the legal practice of no-fault divorce, the increase in women’s education and employment, the growing tendency of men and women of similar education levels to marry, later age at marriage, more cohabitation and unmarried childbearing, etc.). But on the surface – which is where the Wilcox conclusion is drawn – there is not much to go on.

2. The crude divorce rate I got from the Statistical Abstracts shows a little peak in 2006 – not 2007 – followed by two consecutive years of decline, beginning before the recession. So rather than talk about the reason for the decline in the last year – which really just fits in with the falling divorce rates since 1981 – the anomaly is 2006. I have no explanation for that, but in the long run it probably doesn’t matter much.

On the other hand, the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers has surveyed its members twice since the recession started. In the first release last fall, they said 37% expected a drop in divorce filings, compared with 19% who usually see an increase during recessions. This fall they report that 57% of their members experienced a drop in filings, with just 14% seeing an increase. There are no details or methods reported in these releases, so it’s hard to evaluate. But if it’s true – along with the previous evidence that unemployment increases divorce – then it maybe that recessions delay the timing of divorce filings while increasing the divorce rate for those affected in the long run.

On the third hand, Jay Livingston at Montclair State points out that the NY Times reports that, in New York’s recession-year court backlog, ”Cases involving charges like assault by family members were up 18 percent statewide.”

Whether delayed divorce filings contribute to family violence is a question someone might be able to answer when they put all this together. But I doubt the final word will end up as simple as, “Couples too broke to bicker,” as heartwarming as that is. There may be something to the speculation that falling home prices are stalling some divorce plans, but that is not quite the same as developing a newfound appreciation for the benefits of marriage.

I’m sticking with this: in hard times, families are a big part of how people make it through, but hard times are also hard for a lot of marriages. If it’s true that the husband’s job loss especially increases stress on a marriage – as previous research suggests – we may yet see that emerge for the current crisis. If not, maybe something has changed.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.