Cross-posted at Scientopia.

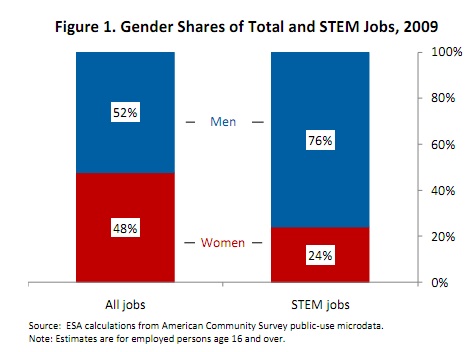

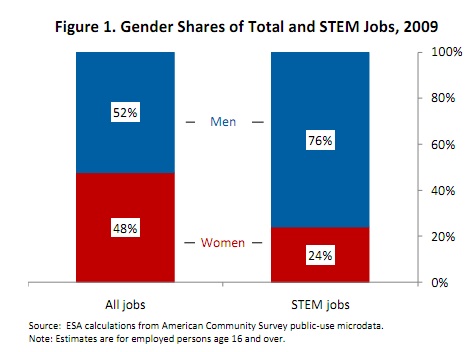

The U.S. Department of Commerce just released a report on the continuing gender gap in STEM jobs – that is, science, technology, engineering, and math. While women make up roughly half of the total paid workforce, they still held only a quarter of STEM jobs as of 2009:

In fact, we saw no change in the gender make-up of STEM fields between 2000 and 2009.

In fact, we saw no change in the gender make-up of STEM fields between 2000 and 2009.

There is significant variation in the gender composition within the STEM category, however. At the high end, women hold 40% of jobs in the physical and life sciences; the low point is engineering, where only 14% of employees are women. And the proportion of women in computer science and math jobs actually fell between 2000 and 2009, from 30% to 27% of workers.

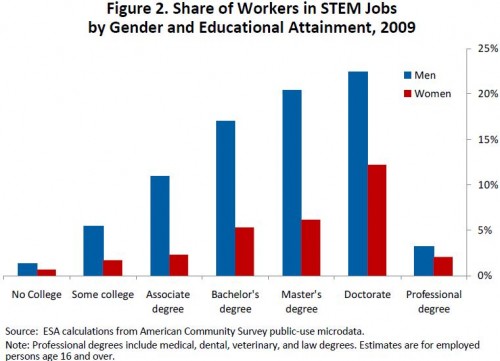

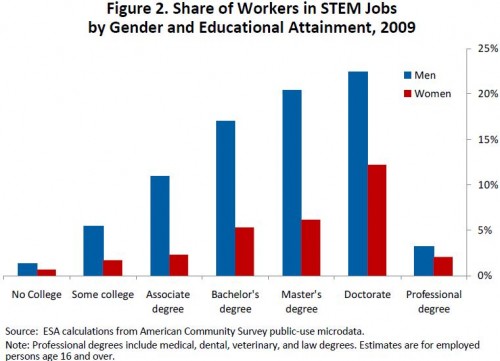

This isn’t simply because of differences in education, either. Here we see the proportion of both men and women in STEM jobs at various educational levels; while increased education correlates with a higher likelihood of having a STEM job for both groups, women are significantly less likely than men at every educational level to have a STEM job:

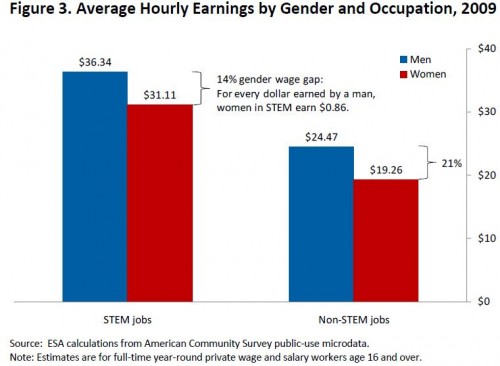

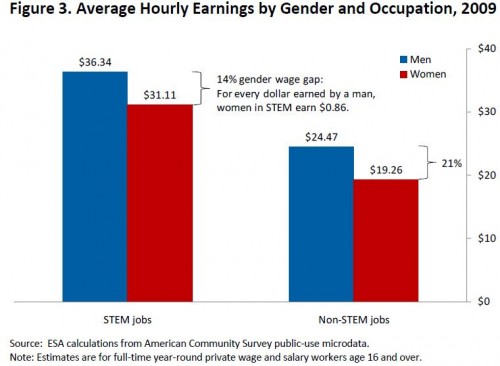

The gender disparity in STEM jobs is especially noteworthy because, on average, STEM occupations pay significantly more than other private-sector jobs, and the gender gap in pay is actually lower than in non-STEM sectors:

The gender disparity in STEM jobs is especially noteworthy because, on average, STEM occupations pay significantly more than other private-sector jobs, and the gender gap in pay is actually lower than in non-STEM sectors:

If we look only at women with bachelor’s degrees, women who earn STEM degrees and work in STEM jobs earn, on average, 29% more than other women.

So the underrepresentation of women in STEM jobs means that women are missing out on some of the best-paying occupations in the U.S.; in fact, this type of gender-segregation of jobs is one of the leading causes of gender gap in yearly and lifetime earnings.

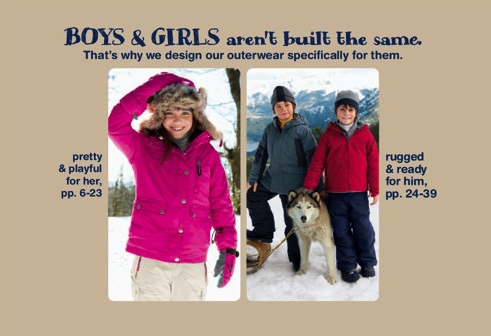

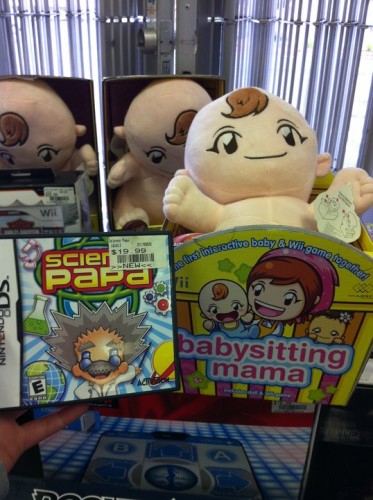

The authors of the report don’t go into detail about potential causes of the gender gap in STEM careers, though they note that among those earning STEM degrees in college, women are significantly less likely than men to hold jobs in related STEM fields. They suggest this might be because STEM jobs are relatively unaccommodating to those who take time off for family obligations (disproportionately women), because of a lack of female role models in STEM fields (including as college professors), or because of gender stereotyping about math or science aptitude (like this, or this if you prefer a t-shirt) that pushes women away from STEM degrees and careers. [UPDATE: Broken links fixed!]

The complex interplay of factors that lead to a gender gap in who holds STEM-sector jobs provides significant challenges to increasing the proportion of women in these occupations — as indicated by the lack of change over the past decade. But particularly as we see increasing economic divergence between well-paid tech and information sector and low-paid service sector jobs, addressing the underrepresentation of women in STEM jobs will be essential as part of any effort to improve women’s lifetime earnings potential and overall economic outlook.