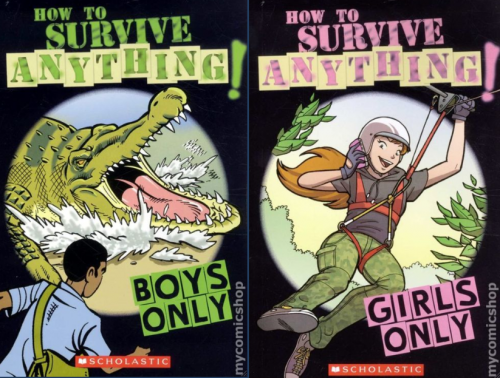

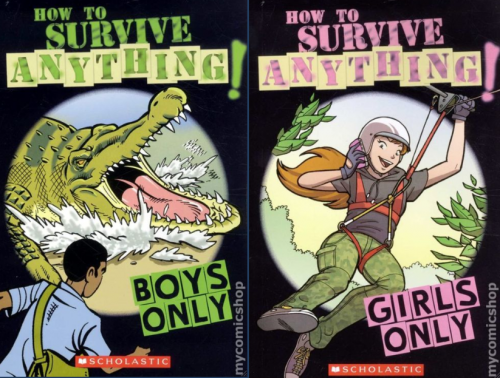

Annie C. and another reader sent us a link to a post by Ryan North at what are the haps about a set of gendered “survival guides” for kids published by Scholastic (and which the publisher now says it won’t continue printing). Boys and girls apparently need very different survival skills, which the other sex shouldn’t know anything about:

In his post, Ryan provides the table of contents for each. What do boys and girls need to be able to survive? For boys, no big surprises — forest fire, earthquake, quicksand, your average zombie or vampire attack, that type of thing, many including, according to teen librarian Jackie Parker, practical and useful tips:

How to Survive a shark attack

How to Survive in a Forest

How to Survive Frostbite

How to Survive a Plane Crash

How to Survive in the Desert

How to Survive a Polar Bear Attack

How to Survive a Flash Flood

How to Survive a Broken Leg

How to Survive an Earthquake

How to Survive a Forest Fire

How to Survive in a Whiteout

How to Survive a Zombie Invasion

How to Survive a Snakebite

How to Survive if Your Parachute Fails

How to Survive a Croc Attack

How to Survive a Lightning Strike

How to Survive a T-Rex

How to Survive Whitewater Rapids

How to Survive a Sinking Ship

How to Survive a Vampire Attack

How to Survive an Avalanche

How to Survive a Tornado

How to Survive Quicksand

How to Survive a Fall

How to Survive a Swarm of Bees

How to Survive in Space

Girls seem to require a very different set of survival skills. Like how to survive a breakout — a skill boys don’t apparently need, though they also get acne. Other handy tips are how to deal with becoming rich or a superstar, how to ensure you get the “perfect school photo,” surviving a crush, whatever turning “a no into a yes” is (persuasiveness, I suppose), picking good sunglasses, dealing with a bad fashion day, and of course “how to spot a frenemy”:

How to survive a BFF Fight

How to Survive Soccer Tryouts

How to Survive a Breakout

How to Show You’re Sorry

How to Have the Best Sleepover Ever

How to Take the Perfect School Photo

How to Survive Brothers

Scary Survival Dos and Don’ts

How to Handle Becoming Rich

How to Keep Stuff Secret

How to Survive Tests

How to Survive Shyness

How to Handle Sudden Stardom

More Stardom Survival Tips

How to Survive a Camping Trip

How to Survive a Fashion Disaster

How to Teach Your Cat to Sit

How to Turn a No Into a Yes

Top Tips for Speechmaking

How to Survive Embarrassment

How to Be a Mind Reader

How to Survive a Crush

Seaside Survival

How to Soothe Sunburn

How to Pick Perfect Sunglasses

Surviving a Zombie Attack

How to Spot a Frenemy

Brilliant Boredom Busters

How to Survive Truth or Dare

How to Beat Bullies

How to be an Amazing Babysitter

Aside from the multiple items clearly focused on appearances, Ryan points out that several others emphasize looks. Camping is “excellent for the skin,” while the seaside survival chapter provides a lot of fashion tips.

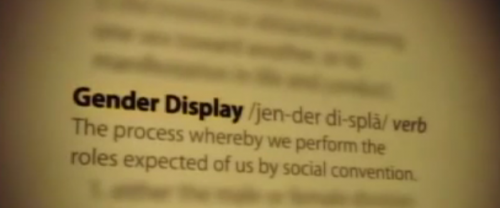

Many of the girls’ tips are about surviving social situations or dealing with emotions — embarrassment, keeping a secret, dealing with bullies. These are all probably more useful to kids than knowing how to survive quicksand, and tips for handling stardom are statistically more likely to be useful at some point than dealing with a T-Rex. So the issue here isn’t that the boys’ guide is inherently more useful or smarter or better; probably all kids should be issued a guide to surviving Truth or Dare (also, dodgeball). But the clear gendering of the guides, with only girls getting tips about dealing with social interactions, emotions, and looks, while outdoorsy injury/natural disaster survival tips are sufficient for boys, illustrates broader assumptions about gender and how we construct femininity and masculinity.