Today I thought we’d do another round-up of gendered children’s stuff, since we’ve gotten a number of submissions. So here we go.

Missy C. noticed that the manufacturer’s product description listed on Amazon for one of the Fisher Price Imaginext Sky Racers took for granted that the toy was for boys, not, say, “kids”:

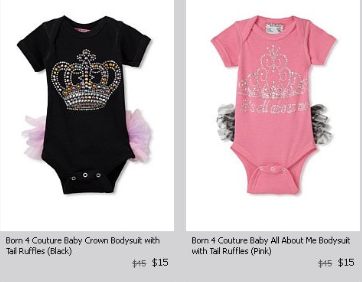

Monica C., meanwhile, noticed another example of the association of girls with a diva-ish princess center-of-attention persona when looking at onesies for sale at My Habit. Options included “born fabulous,” “high maintenance,” “born to wear diamonds,” and “it’s all about me,” among others:

Similarly, Melanie J. saw some baby booties for sale at retail chain JR’s in North Carolina that reinforce the idea that boys are mischievous while girls are materialistic:

You can buy them gendered vitamins as well. Nathan, who writes at 1115, sent in this photo he took at Target:

Pete & Emily in Norwich, UK, noticed that you can now allow your hamsters to inhabit gendered worlds too, if you’d like; they sent us this photo they took at a pet store:

But we do have two counter-examples this time! Jackie H. took a photo of a kitchen set she saw for sale at Meijer, which shows both a boy and a girl using it:

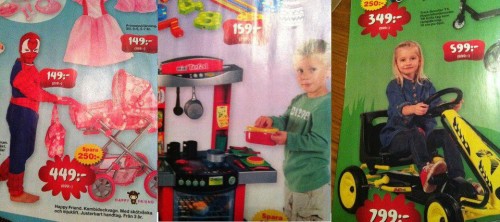

And Isabeau P.S., Jesse W., and Anne Sofie B. all sent in images from the catalog for Swedish toy maker Leklust (two of the images were discussed at Mommyish):