Recently, reader Nicole D. was shopping at Home Depot and noticed a sign near the front that described ways employees are “empowered.” When we think of empowered employees, we might think of issues such as fair pay, decent benefits, access to full-time work, a way for employees to have input in the creation of workplace policies, or other factors that affect the work environment. But what struck Nicole was how being “empowered” was defined to align with corporate goals.

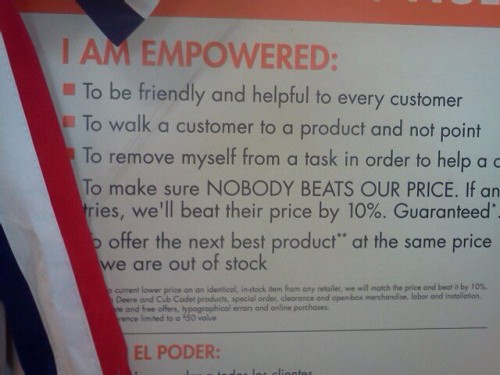

What are Home Depot employees empowered to do? To provide good customer service, basically — that is, to be “friendly and helpful to every customer,” to actually show customers what they’re looking for and “not point” to it, and to make sure Home Depot’s price-matching program is implemented:

In Class Acts: Service and Inequality in Luxury Hotels (2007), Rachel Sherman discusses how luxury hotels ensure the level of service their customers expect. Sherman writes, “Managers…face a difficult task. They must convince their employees…to go out of their way for guests, satisfying and surprising guests in largely intangible ways” (p. 63). Among other strategies, they encourage employees to break rules when necessary to provide the level of customer service their guests expected. This autonomy to circumvent certain rules in order to meet the larger goals of satisfying customers was seen by guests and employees as a mark of luxury service. Luxury service providers, such as the Ritz-Carlton, were in the forefront of the move to “empower” employees, an idea that has spread well beyond the luxury sector.

Sherman found that employees did value even seemingly minor forms of autonomy on the job. It made them feel like they had some power in the workplace. I know when I worked in food service, small things like getting to organize break schedules ourselves or decide what to offer as a special were highly appreciated. But Sherman shows that this language of autonomy can obscure the lack of specific changes that would have materially improved workers’ lives. For instance, while the luxury hotels she studied complained constantly about the difficulty of finding good staff, and framed their employees as intelligent professionals making autonomous decisions in order to serve guests’ needs, the jobs didn’t pay particularly well.

As Nicole pointed out, this a very limited form of empowerment. Employees might be given some autonomy, but it is to be used only in the service of improving outcomes for the corporation. In the case of Home Depot, some aspects of empowerment simply reframe externally-imposed requirements (such as being polite and helpful to customers) as forms of autonomy. The corporate discourse of empowerment presents it as synonymous with corporate goals. The wider array of factors that might empower workers are absent from the conversation, which frames empowerment entirely from the perspective of the company’s interest in providing better customer service without necessarily providing better pay, benefits, or other concrete improvements to workers’ lives.