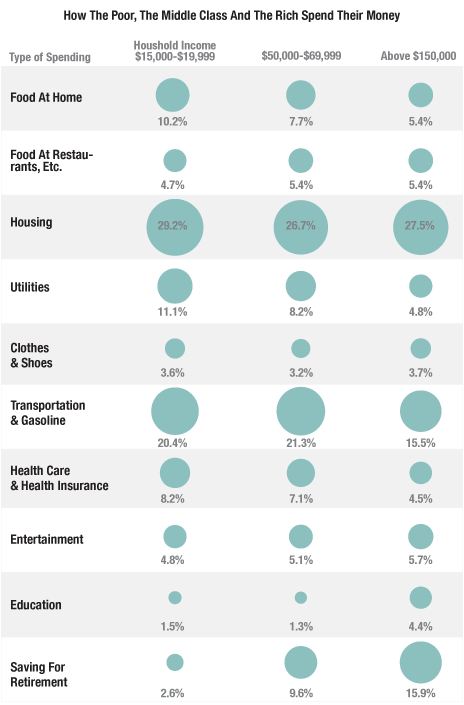

NPR’s Planet Money blog posted an interesting image of differences in how we allocate income based on how much we make. The image looks at three income groups and shows what percent of their household income budget they spend various categories, using Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey data:

As we see, the largest expense for every group is housing; for the low-income group, 40% of their income goes just to paying for a place to live. They also use more of their income to cover basic necessities — utilities, food eaten at home, transportation.The high-income group, on the other hand, spends quite a bit more on education.

Look at that last row: saving for retirement (which includes Social Security contributions). This is a particularly striking difference. The affluent are able to put away a significant portion of their income for retirement; for those living just above the poverty line, it’s much, much less than the amount financial planners would recommend (even the middle-income group is saving about the minimum amount generally recommended to prepare for retirement). When so much of your income goes to simply meeting day-to-day needs, saving for the future is a luxury many just cannot afford.

UPDATE: NPR has updated their post, saying the image they had up initially incorrectly. They posted a new image, with notably lower spending on housing:

Eagle-eyed reader David C. pointed this out to me. The revised numbers seem surprisingly low to both of us.Looking at the NPR post again, I think I misunderstood what they were representing; I think this isn’t the percent of total income, but rather % of the household budget, which may not be identical. That said, I looked at some Consumer Expenditure Survey data (here and here) and can’t get the numbers to work out to what they’re showing in the updated image. If someone can, please send us a note at socimages(at)thesocietypages.org and we’ll do another update. Thanks!