A while back, David Dismore posted about his archive of suffragist postcards, which appeared in the early 1900s as part of the campaign for women’s right to vote. The postcards got the messages of the movement across in short, clear, and often humorous ways.

Those opposed to women’s suffrage also used postcards to get their message out to the public. The Palczewski Postcard Archive at the University of Northern Iowa, sent to us by Katrin, has a number of great examples that illustrate the frames used to present women’s full political participation as threatening.

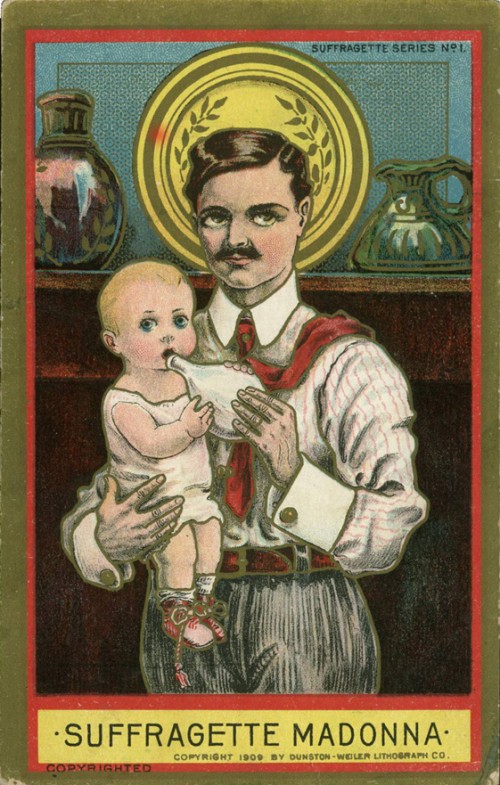

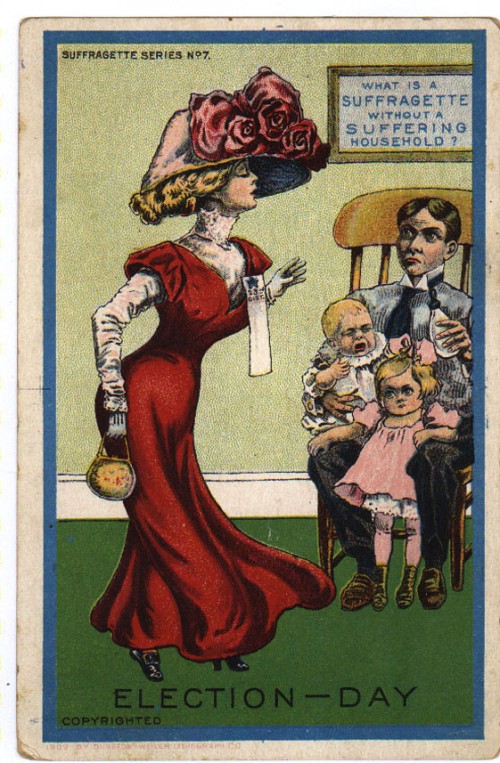

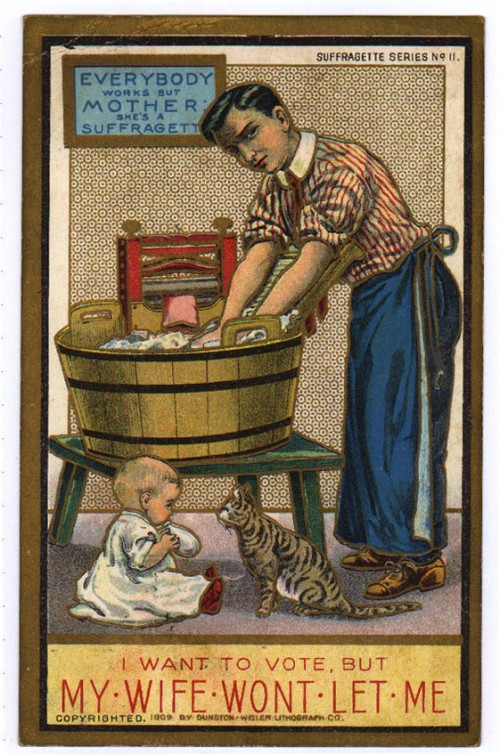

For instance, a 12-card series produced by Dunston-Weiler Lithographic Company presented suffrage as upending the gender order by masculinizing women and feminizing men. Suffragists, the postcards tell us, cause women to abandon their household duties and become aggressive and unladylike:

In an effort to win her own rights, then, women make their families suffer — a message complete with visuals that don’t seem out of place among stock images of crying babies and their working mothers today, as Katrin pointed out:

Equality in voting rights is clearly presented as female domination:

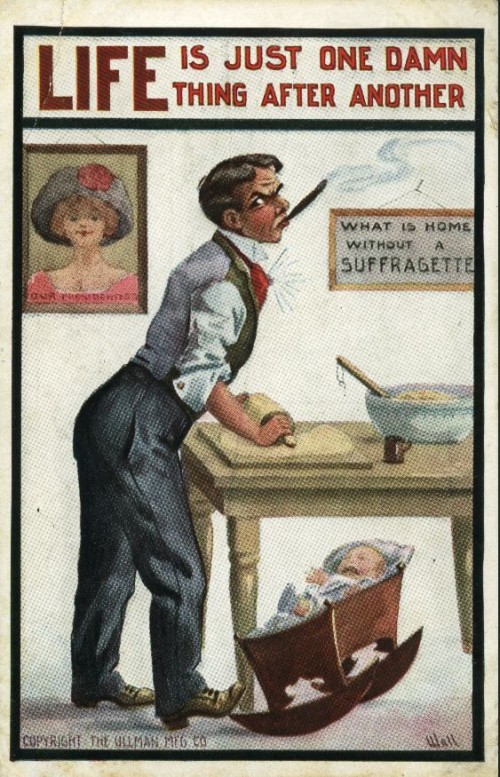

Postcards issued by other groups reflect these same themes. The clear message is that giving women the right to vote threatens men, the family, and the entire natural order of things:

The archive has a bunch more examples, categorized by various themes — including Cats and Suffrage, because lolcats are timeless.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.