For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2012. Cross-posted at Global Policy TV and Pacific Standard.

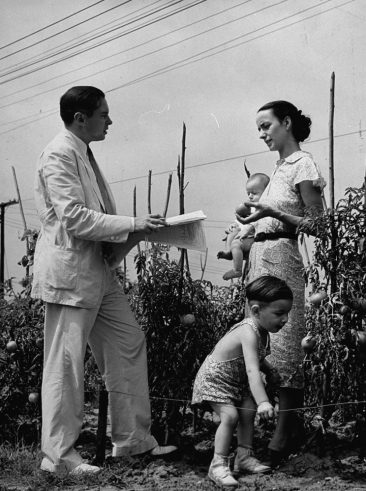

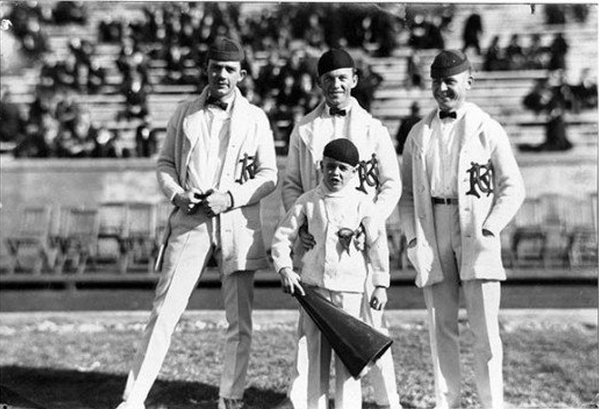

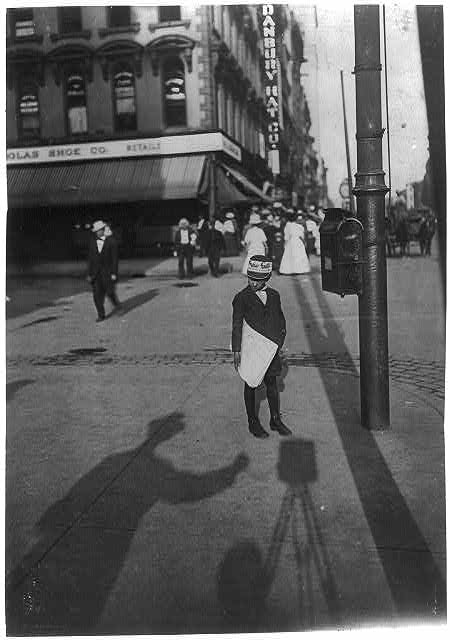

Publicizing the release of the 1940 U.S. Census data, LIFE magazine released photographs of Census enumerators collecting data from household members. Yep, Census enumerators. For almost 200 years, the U.S. counted people and recorded information about them in person, by sending out a representative of the U.S. government to evaluate them directly (source).

By 1970, the government was collecting Census data by mail-in survey. The shift to a survey had dramatic effects on at least one Census category: race.

Before the shift, Census enumerators categorized people into racial groups based on their appearance. They did not ask respondents how they characterized themselves. Instead, they made a judgment call, drawing on explicit instructions given to the Census takers.

On a mail-in survey, however, the individual self-identified. They got to tell the government what race they were instead of letting the government decide. There were at least two striking shifts as a result of this change:

- First, it resulted in a dramatic increase in the Native American population. Between 1980 and 2000, the U.S. Native American population magically grew 110%. People who had identified as American Indian had apparently been somewhat invisible to the government.

- Second, to the chagrin of the Census Bureau, 80% of Puerto Ricans choose white (only 40% of them had been identified as white in the previous Census). The government wanted to categorize Puerto Ricans as predominantly black, but the Puerto Rican population saw things differently.

I like this story. Switching from enumerators to surveys meant literally shifting our definition of what race is from a matter of appearance to a matter of identity. And it wasn’t a strategic or philosophical decision. Instead, the very demographics of the population underwent a fundamental unsettling because of the logistical difficulties in collecting information from a large number of people. Nevertheless, this change would have a profound impact on who we think Americans are, what research about race finds, and how we think about race today.

See also the U.S. Census and the Social Construction of Race and Race and Censuses from Around the World. To look at the questionnaires and their instructions for any decade, visit the Minnesota Population Center. Thanks to Philip Cohen for sending the link.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.