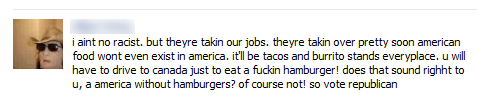

The U.S. is not a very race-literate society. We aren’t taught much about the history of race relations or racial inequality in school and almost nothing about how to think about race or how to talk to one another about these theoretically and emotionally challenging issues. Many Americans, then, don’t have a very sophisticated understanding of race dynamics, even as most of them want racial equality and would be horrified to be called “racist.”

In teaching Race and Ethnicity, then, I notice that some of the more naive students will cling to color-blindness. “Race doesn’t matter,” they say, “I don’t even see color.” Being colorblind seems like the right thing to be when you’ve grown up being told that (1) all races are or should be equal and (2) you should never judge a book by its cover. It is the logical outcome of the messages we give many young people about race.

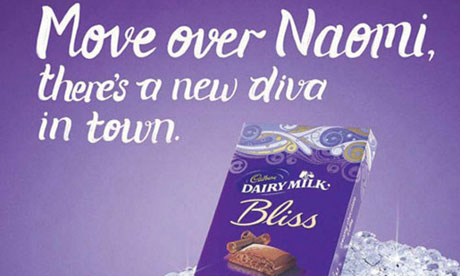

But, of course, color blindness fails because race, despite being a social invention, still matters in our society. Enter the ongoing scandal about the Cadbury candy bar ad featuring Naomi Campbell, sent in by Dolores R., Jack M., and Terri. The ad compares the Dairy Milk Bliss Bar to Campbell. It reads: “Move over Naomi, there’s a new Diva in town.”

The ad has been called racist because it compares Campbell to a chocolate bar; chocolate is a term sometimes used to describe black people’s skin color or overall sexual “deliciousness.” The ad, then, is argued to be foregrounding skin color and even playing on stereotypes of black women’s sexuality.

So what happened here? One the one hand, I see the critics’ point. On the other, I can also imagine the advertising people behind this ad thinking that they want to link the candy bar with the idea of a diva (rich, indulgent, etc.), and choosing Campbell because she is a notorious diva, not because she’s a black, female supermodel. They could argue that they were being colorblind and that race was not at all a consideration in designing this ad.

The problem is that being colorblind in a society where race still colors our perceptions simply doesn’t work. The truth is that race may not have been a consideration in designing the Cadbury ad, but it should have been. Not because it’s fun or functional to play with race stereotypes, but because racial meaning is something that must be managed, whether you like it or not. This is where Cadbury failed.

In my classes, I ask my earnestly-anti-racist students to replace color-blindness with color-consciousness. We need to be thoughtful and smart about race, racial meaning, and racial inequality. Racism is bad, but color-blindess is a just form of denial; being conscious about color — seeing it for what it is and isn’t, both really and socially — is a much better way to bring about a just society.

Cadbury, for what it’s worth, has apologized.

See also the Oreo Barbie, the Black Lil’ Monkey Doll, the Obama Sock Monkey, Disparate Pricing for Black and White Dolls, and Accidentally Illustrating Evil with Skin Color.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.