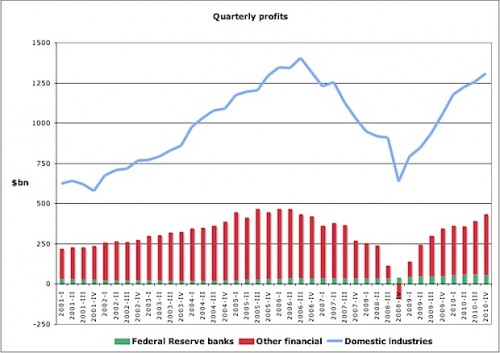

We’ve posted previously about the ways in which World War II posters aimed at U.S. soldiers warned against “venereal disease” (what we now know as sexually transmitted infections) by personifying them as dangerous, diseased women. Molly W. and Jessica H. have shown us to a new source of propaganda posters, so now seems as good a time to revisit the phenomenon. In our previous post, I articulated the problem as follows:

Remember, venereal disease is NOT a woman. It’s bacteria or virus that passes between women and men. Women do not give it to men. Women and men pass it to each other. When venereal disease is personified as a woman, it makes women the diseased, guilty party and men the vulnerable, innocent party.

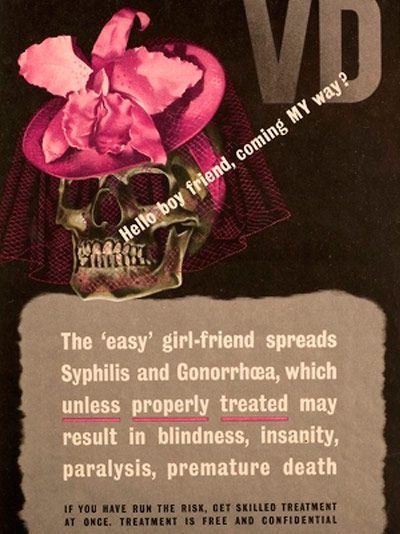

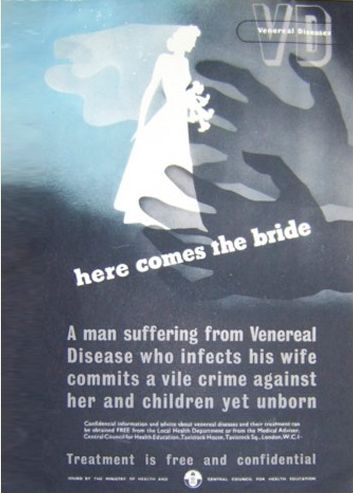

This first poster is an excellent example. In it, the woman is synonymous with death:

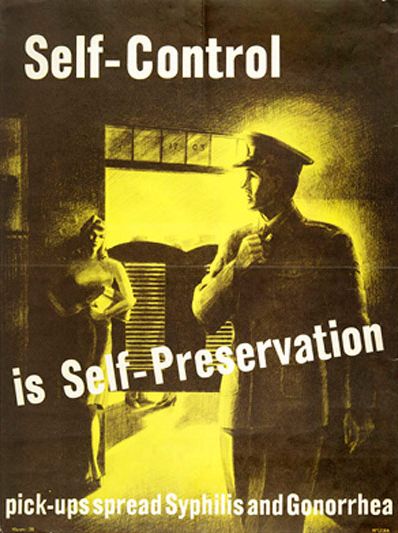

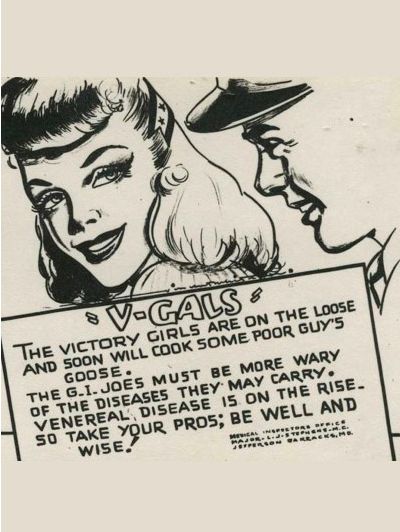

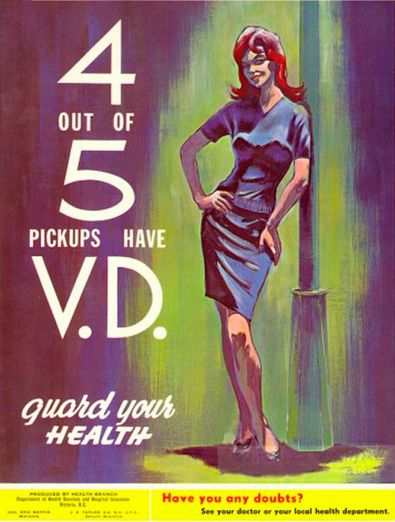

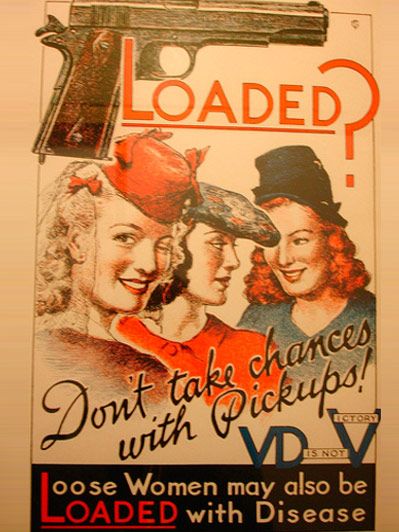

In other posters, women are simply seen as the diseased party. Concern that a soldier might pass disease to “pick ups” and “prostitutes” is unspoken. This is funny, given that the reason for this propaganda was sky-high rates of VD among soldiers.

So “pick ups” and “prostitutes” were seen as vectors of disease. They were the guilty party. In contrast, wives are portrayed as innocent. Another example of the dividing of women into virgins and whores:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.