Appearances and Publications:

After I posted about the Jimmy Kimmel prank in which he encouraged parents to film their kids getting “bad” presents, I had the opportunity to inform a New York Times article about the subject. I discussed the social rules of the Christmas gift-giving (and the importance of teaching kids how to be the butt of a joke). My first time in the NYT. w00t!

Also, I’m proud to report that a paper I co-wrote with Caroline Heldman has been published in a new book titled Sex For Life: From Virginity to Viagra, How Sexuality Changes Throughout Our Lives (edited by Laura Carpenter and John DeLamater, and published by NYU Press). Our chapter is about first-year college students experiences with hook up culture. You can get a sneak peak here.

Pinterest!

Over the holiday I went sort of bonkers and decided to start up a Pinterest site for SocImages. Pinterest is a virtual “pin board” where people can collect images from around the web. I uploaded our entire archive to the site: 4,002 posts and 8,040 images. It will let you peruse our images much more quickly. If anything inspires, you can click through to the blog to read the analysis. These are the “boards” we have so far:

- All SocImages Content

- Re-Touching and Photoshop

- Vintage Ads and Products

- Racial/Ethnic Objectification

- Sexy Toy Make-Overs

- Gendered Parenting and Housework

- Heteronormativity

- Social Construction

- The Social Construction of Race

They look like this (then you scroll down):

Best of December:

Meanwhile, our fabulous intern, Norma Morella, collected the stuff ya’ll liked best from this month. Here’s what she found:

- Jay Livingston, Graphic Design the Fox News Way

- Lisa Wade, Why I’m Not Married

- Gwen Sharp, Example of Socialization: Baby Rapper

- Gwen Sharp, Marketing by Masculinizing the Feminine

- Sophy Bot, A Hipster By Any Other Name

- Lisa Wade, American vs. International News: Time and Newsweek

- Caroline Heldman, Pennsylvania Public Service Announcement Blames Rape Victims

- Lisa Wade, Behind the “Perfect” Body: Models and Bodybuilders

- Lisa Wade, Now You’ll Never Forget What a Venn Diagram Is

Best of 2011:

Gwen and I ran our favorite posts from 2011 over the last five days. Just in case you missed them, here’s a list:

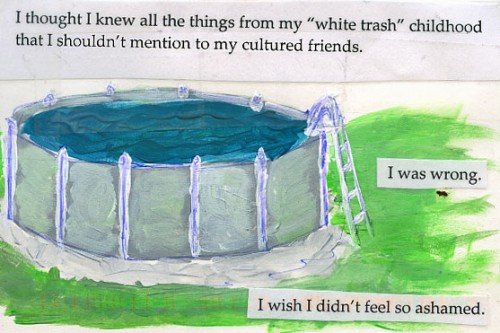

- The Mental Burden of a Lower Class Background

- Of What are We Capable? Human Echolocation

- A Thoughtful Response to the “Asians in the Library” Rant

- Formula for a Successful American Movie

- Gender, Obentos, and the State in Japan

- Babies Learn How to Have a Conversation

- In Defiance of Title IX: Colleges Report Male Athletes as Women

- Art and Attribution: What is an Artist?

- How to Make an Art: By Hennessey Youngman

- The Innovation Trap: How the iPhone Isn’t Saving America

- Change Blindness

- Cultural Differences in Cognitive Perception

- Luxury and the Consumption of Labor

- Are Game Show Audiences Trustworthy

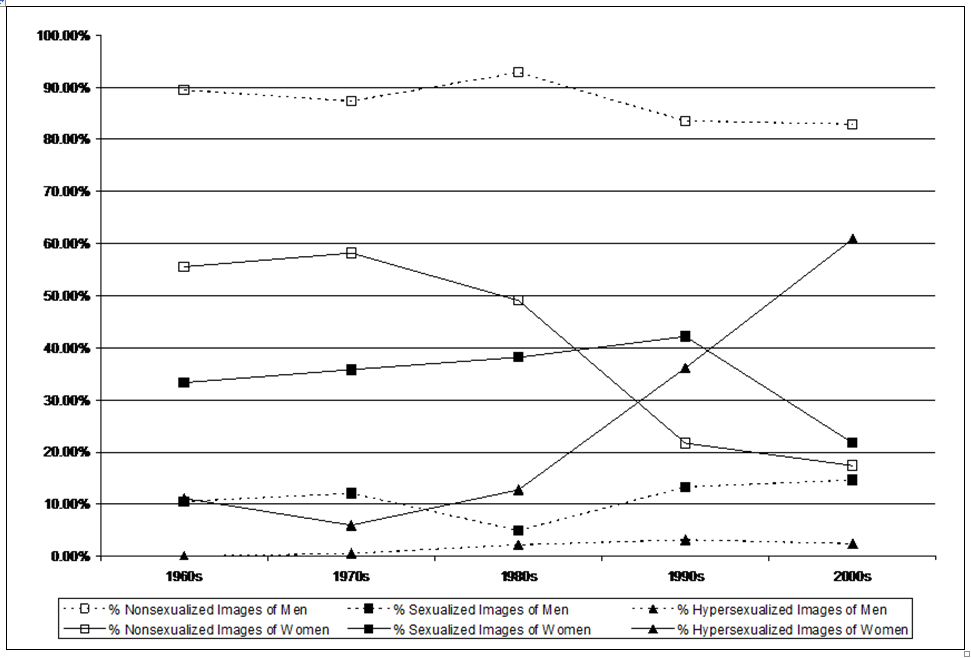

- Gender, Sexualization, and Rolling Stone

- Best Comic Ever: The Scientific Process

- Cousin Marriage

- The Hidden Beneficiaries of Federal Programs

- A Critique of Capitalism by G.A. Cohen

- What Makes a Body Obscene?

Over at his blog, Family Inequality, SocImages Contributor Philip Cohen made a list of his best liked posts from 2011 too. Check them out here.

Social Media ‘n’ Stuff:

Finally, this is your monthly reminder that SocImages is on Twitter, Facebook and, now, Pinterest. Gwen and I and most of the team are also on twitter: