Katrin sent along a vintage (apparently 1957) Pepsi commercial I thought you might enjoy, as it has all the classics: lightly mocking tone about women’s supposed competitiveness with one another and obsession with shopping, reminder that attractive = thin, and presentation of marriage as the ideal, ultimate victory for all women:

Archive: 2011

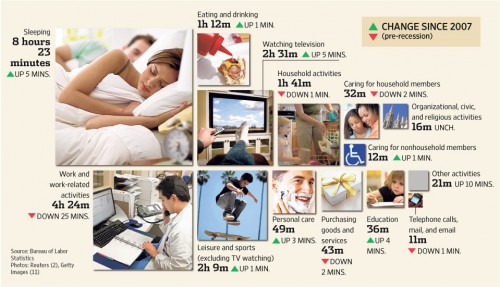

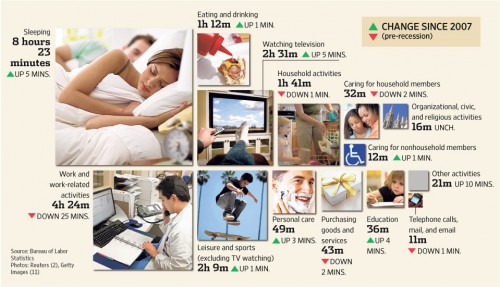

Sangyoub Park let us know that the Bureau of Labor Statistics has released the results of the 2010 American Time Use Survey, a study that looks at what we do with our time. They haven’t released any charts of the 2010 data yet, but the Wall Street Journal posted an article with an image that summarizes the changes since 2007, before the recession began. Not surprisingly, on average Americans are spending less time working and more time sleeping and watching TV, among other activities:

Keep in mind those numbers are daily averages that even out activity that is often not evenly distributed in real life (such as work, where weekly hours worked are averaged across all 7 days).

These changes seem insignificant when you look at them; so what if Americans are, on average, sleeping 5 extra minutes a day, or spending 2 minutes less buying things? But when aggregated across the entire U.S. population aged 15 years or older, these add up to major shifts in family and work life as well as economic activity.

There’s a video to accompany the story:

Finally, they have an interactive website where you can enter your own time use in major categories (to the best you can estimate it) and see how you compare to national averages.

We’ll follow up with more detailed posts once the BLS starts posting relevant charts.

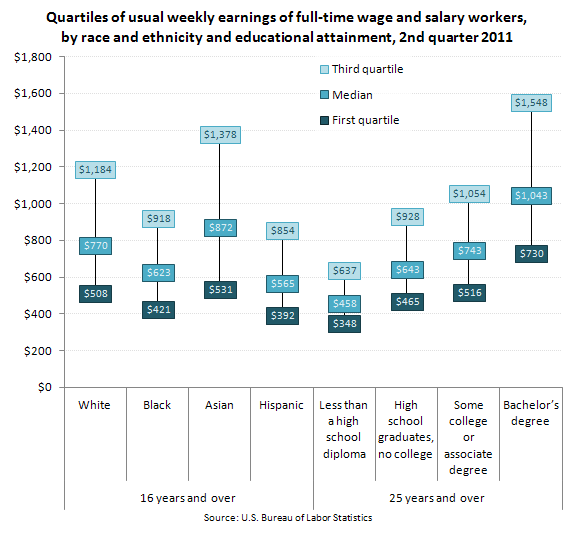

Kelsey C. sent in a some great data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that helps illustrate why variance matters as much as a measure of the average. The figure shows the median income by race and education level, as well as the typical earnings of each group’s members in the third quartile (or the 75th percentile) and first quartile (or the 25th percentile). What you see is that the median earnings across these groups is different, but also that the amount of inequality within each group isn’t consistent. That is, some groups have a wider range of income than others:

So, Asians are the most economically advantaged of all groups included, but they also have the widest range of income. This means that some Asians do extremely well, better than many whites, but many Asians are really struggling. In comparison, among Blacks and Hispanics, the range is smaller. So the highest earning Blacks and Hispanics don’t do as well relative to the groups median as do Whites and Asians.

Likewise, dropping out of high school seems to put a cap on how much you can earn; as education increases it raises the floor, but it also raises the variance in income. This means that someone with a bachelors degree doesn’t necessarily make craploads of money, but they might.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

The Atlantic recently posted an article by Conor Friedersdorf about the results of polls conducted by the Abu Dhabi branch of the Gallup organization, in cooperation with the U.S. branch, on the political attitudes of various religious groups in the U.S., particularly focusing on how Muslim Americans compare to other groups. The respondents were chosen as a subsample of respondents to ongoing Gallup telephone polling of hundreds of thousands of randomly-selected Americans each year. One major caveat: though Gallup reports that the overall sample is representative of the U.S. population as a whole, the response rate for the subsample of 2,482 individuals chosen to investigate these issues in depth was low: 21% for the first wave, 34% for the second (the methodology begins on p. 57 of the full report). The authors argue the data have been weighted to ensure representativeness, but the low response rates require caution.

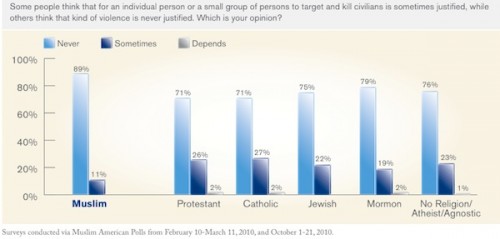

One set of questions looked at attitudes about violence toward civilians, whether by military or non-military groups. As we see, Muslims were more likely than any other group to say targeting civilians is never justified:

But every group overwhelmingly said it is “never” justified for a non-military group to attack and kill civilians, though Friedersdorf points out that a not insignificant minority of Americans said that targeting civilians is at least somewhat justified — a proportion that might have been lower if the word “terrorism” had been used to describe targeting civilians, I suspect.

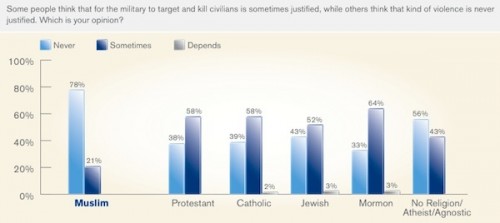

However, Americans are much more divided on whether the military is sometimes justified in targeting and killing civilians. Muslim Americans overwhelmingly reported it is “never” justified, but the only other group where over half of respondents held that view was for non-believers/agnostics. A solid majority of Protestants, Catholics, and Mormons, and a slim majority of Jews, said that it is “sometimes” justified for the military to target civilians:

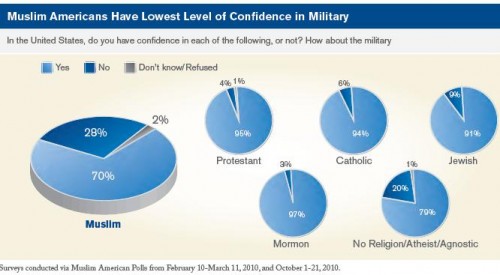

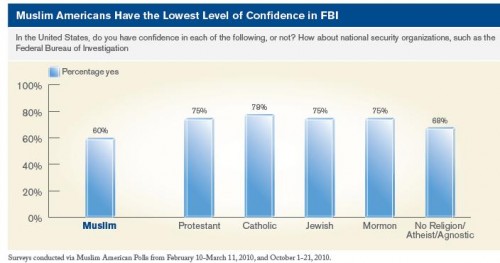

The full report includes data on a wide variety of indicators of political engagement and perceptions of quality of life and the future. Consistent with the graphs above, Muslim Americans have less confidence in the military and law enforcement agencies such as the FBI than all other groups (with non-believers/agnostics have the second-lowest levels of confidence):

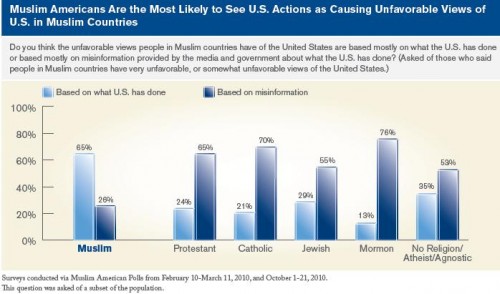

One major area of difference is in perceptions of why people in Muslim countries might have unfavorable views of the U.S. Muslims Americans were the only group where a majority (65%) thought that U.S. actions were mostly responsible for such unfavorable views. For every other group, the majority thought that misinformation distribution by media outlets or governments was the major cause of unfavorable views of the U.S.:

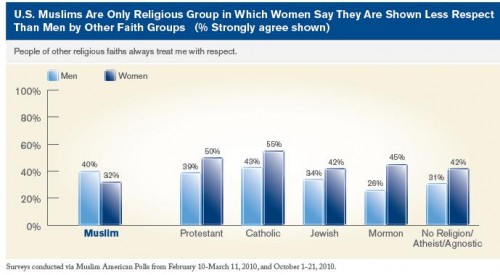

Muslim Americans were much more likely than all other groups to believe they have experienced racial or religious discrimination. Interestingly, Muslim Americans were the only group where women were less likely than men to say they are always treated with respect by members of other religious groups:

The report authors suggest this may be partially due to Muslim women who wear hijab being visibly recognizable as Muslims in a way that may lead to negative interactions or comments from others.

However, despite higher levels of perceived discrimination, overall, Muslim Americans had a generally optimistic view of their future in the U.S.; the majority of respondents said they will be thriving in the future, and they were slightly less likely than other groups to believe they will be struggling:

I’ve just posted a few items that stood out to me here. Check out the full report for a much fuller discussion of attitudes toward the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, perceptions about quality of life in the U.S., major sources of self-identification (religion, ethnicity, citizenship, etc.), whether Muslims are loyal Americans, and more.

Cross-posted at Montclair Socioblog.

Peter Berger* takes issue with the phrase “on the wrong side of history.” Mostly, he takes issue with those who use that phrase. Specifically, he refers to proponents of gay marriage who claim that the Defense of Marriage Act is “on the wrong side of history” (or in Berger’s acronym, OTWSOH) The trouble with this statement, Berger says, is that “we cannot know who or what is on the right side.”

Berger is correct (though he doesn’t offer much explanation) because the history that people are referring to hasn’t happened yet. The history of OTWSOH is the future, and we can’t know the future. However — and here’s where Berger is wrong — we can make a pretty good guess about some things that will happen, at least in the short-run future. We can look at the trend — Americans becoming more accepting of gay marriage — and predict that the trend will continue, especially when we see that the young are more accepting than the old.

But beyond the short-run, who knows? It’s possible that the values, ideas, and even facts that are right today will, decades or centuries from now, be wrong. So it may turn out that at some time in the future, people will think that gay marriage is a plague on civilization, that human slavery is a pretty good idea, that Shakespeare was a hack, and that Kevin Federline was a great musician.

The trouble with asking history, “Which side are you on?” is that history doesn’t end. It’s like the possibly true story of Henry Kissinger asking Chou En Lai about the implications of the French Revolution. Said the Chinese premier, “It’s too early to tell.”

At what point can we say, “This is it. Now we know which side history is on”? We can’t, because when we wake up tomorrow, history will still be rolling on. Duncan Watts, in Everything Is Obvious… Once You Know the Answer, makes a similar point using the historical film “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” The two robbers flee the US and go to Bolivia. Good idea? Since we know how the movie ends — that sepia freeze frame — we can safely say, “No, bad idea.”

But if we had stopped the movie twenty minutes earlier, it would have seemed like a good idea. The vindictive lawman and his posse were about to find and kill them. A few minutes later in the film, Bolivia seemed again like a bad idea – it was a miserable place. Then, when their robberies in Bolivia were easy and lucrative, it seemed again like a good idea. And then, they got killed. Butch was 42, Sundance 31.

But history is not a movie. It doesn’t end. So at least for the long run, the OTWSOH argument claims certainty about what is at best speculation. It says, “We know what will happen, and we know that we are on the right side of history, and those who are not with us are on the wrong side of history.” Some religious folks make similar claims not about history but about God. “We are on God’s side,” they say, “and those who disagree with us are against God.” They tend to populate the political right. The OTWSOH argument, Berger says, “comes more naturally to those on the left,” mostly because that is the side that is pushing for historical change. The two sides are indulging in a similar fallacy — knowing the unknowable — a fallacy which, to those who don’t share their views, makes them appear similarly arrogant.

————————

* Yes, this is the same Peter Berger whose Social Construction of Reality (co-written with Thomas Luckman), published forty-five years ago, has an important place in sociology’s relatively short history.

HT: Gabriel Rossman

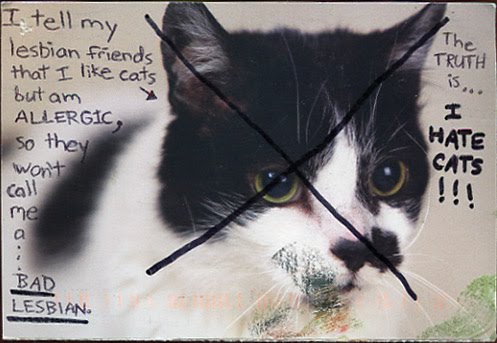

In my Sociology of Gender course I talk about how gender conformity isn’t simply a matter of socialization, but often a response to active policing by others. Single women usually avoid having too many cats, for example, not only because they’ve been taught that too many cats sends the wrong signal, but because they may be called a “cat lady” by their friends (a joke-y slur suggesting that she is or will be a batty old spinster). Or her best friend, with her best interests in mind, may discourage her from adopting another cat because she knows what people think of “cat ladies.”

People who find community in subcultures that are seen as “alternative” to the “mainstream” often feel like they are freed of such rules. But these subcultures often simply have different rules that turn out to be equally restrictive and are just as rigidly policed.

A recent submission to PostSecret, a site where people anonymously tell their secrets, reminded me of this. In it a lesbian confesses that she hates cats. Because of the stereotype that women love cats, the “cat lady” stigma may be lifted in lesbian communities. This lesbian, however, doesn’t feel freed by the lifting of this rule, but instead burdened by its opposite: everyone has to like cats. So she feels compelled to lie and say that she’s allergic.

Related, see our post on a confession, from another lesbian, about suppressing the fact that she’s really quite girly.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Cross-posted at Scientopia.

A couple of days ago I posted a video about stereotypes of Native Americans in video games, including the Hot Indian Princess. Though the video discussed video games specifically, these tropes are common in other area of pop culture as well. Dolores R. sent in a great example. Over at Beyond Buckskin, Jessica Metcalfe posted about the 2011 Caribana Parade in Toronto. This year the parade theme was Native America, including various sections such as Amazon Warriors, Lost City of the Aztecs, Brazilian Amerindians…and Tribal Princesses. Here’s a Tribal Princess costume provided by one band, Callaloo (it’s now sold out).

A commenter on Metcalfe’s post takes exception with criticisms of these costumes and the parade theme, saying,

[This is a] celebration of historic alliances between African Diaspora peoples and Native peoples. In New Orleans, the tradition was a specific response to racist laws that placed Native and other POC communities in a common frame of reference. This tradition is almost 200 years old among Caribbean/Diaspora people in North America…you are making a tremendous mistake by attacking a part of Afro-Caribbean culture as if this was the same as an expression of White/Euro privilege.

So the argument is that this can’t be problematic cultural appropriation or propagation of the sexualized Indian Princess trope because it is part of an event meant to celebrate and recognize the histories and cultures of groups that have themselves been the target of discrimination and political/cultural exclusion. Certainly there is an important cultural and historical context there that, the commenter argues, distinguishes these costumes from, say, the current fad of “tribal” clothing in fashion.

And yet, that argument seems to discursively claim a right to represent Native Americans in any way without being subject to criticisms of stereotyping or cultural appropriation. For instance, the Apache were not a Caribbean tribe (though the Lipan Apache moved far into southeastern Texas by the late 1700s, coming into regular contact with Texas Gulf tribes). Does this sexualized “Apache” costume, as imagined by non-Apaches and sold to the general public, differ greatly from other appropriations and representations of Native American culture and identity as fashion statement?

This feels a little like a different version of the “But we’re honoring you!” argument used in efforts to defend Native American sports mascots — that any concern the viewer has is only due to their lack of understanding of the reason for the depiction of Native Americans, not because that depiction might be, in fact, problematic.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Cross-posted at Ms. and Jezebel.

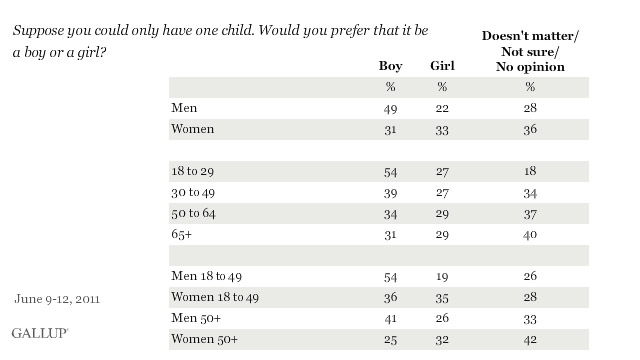

In a previous post I’ve argued against framing a preference for boy children as “culturally Asian.” New data from Gallup, sent in by Kari B., shows that this preference is alive and well among Americans, at least among young men. While women are most likely to have no opinion and about equally likely to prefer a girl or boy, men are significantly more likely to prefer a boy. This preference is strongest among younger men, but still present among men over 50. Whereas women become increasingly indifferent with age and, secondarily, begin to prefer girls.

The editors at CNN note that, since children are mostly born to young people, and indifferent women may bend to men’s preferences, new sex selection technologies threaten to create a gender imbalance in the U.S.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Sangyoub Park let us know that the Bureau of Labor Statistics has released the results of the 2010 American Time Use Survey, a study that looks at what we do with our time. They haven’t released any charts of the 2010 data yet, but the Wall Street Journal posted an article with an image that summarizes the changes since 2007, before the recession began. Not surprisingly, on average Americans are spending less time working and more time sleeping and watching TV, among other activities:

Keep in mind those numbers are daily averages that even out activity that is often not evenly distributed in real life (such as work, where weekly hours worked are averaged across all 7 days).

These changes seem insignificant when you look at them; so what if Americans are, on average, sleeping 5 extra minutes a day, or spending 2 minutes less buying things? But when aggregated across the entire U.S. population aged 15 years or older, these add up to major shifts in family and work life as well as economic activity.

There’s a video to accompany the story:

Finally, they have an interactive website where you can enter your own time use in major categories (to the best you can estimate it) and see how you compare to national averages.

We’ll follow up with more detailed posts once the BLS starts posting relevant charts.

Kelsey C. sent in a some great data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that helps illustrate why variance matters as much as a measure of the average. The figure shows the median income by race and education level, as well as the typical earnings of each group’s members in the third quartile (or the 75th percentile) and first quartile (or the 25th percentile). What you see is that the median earnings across these groups is different, but also that the amount of inequality within each group isn’t consistent. That is, some groups have a wider range of income than others:

So, Asians are the most economically advantaged of all groups included, but they also have the widest range of income. This means that some Asians do extremely well, better than many whites, but many Asians are really struggling. In comparison, among Blacks and Hispanics, the range is smaller. So the highest earning Blacks and Hispanics don’t do as well relative to the groups median as do Whites and Asians.

Likewise, dropping out of high school seems to put a cap on how much you can earn; as education increases it raises the floor, but it also raises the variance in income. This means that someone with a bachelors degree doesn’t necessarily make craploads of money, but they might.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

The Atlantic recently posted an article by Conor Friedersdorf about the results of polls conducted by the Abu Dhabi branch of the Gallup organization, in cooperation with the U.S. branch, on the political attitudes of various religious groups in the U.S., particularly focusing on how Muslim Americans compare to other groups. The respondents were chosen as a subsample of respondents to ongoing Gallup telephone polling of hundreds of thousands of randomly-selected Americans each year. One major caveat: though Gallup reports that the overall sample is representative of the U.S. population as a whole, the response rate for the subsample of 2,482 individuals chosen to investigate these issues in depth was low: 21% for the first wave, 34% for the second (the methodology begins on p. 57 of the full report). The authors argue the data have been weighted to ensure representativeness, but the low response rates require caution.

One set of questions looked at attitudes about violence toward civilians, whether by military or non-military groups. As we see, Muslims were more likely than any other group to say targeting civilians is never justified:

But every group overwhelmingly said it is “never” justified for a non-military group to attack and kill civilians, though Friedersdorf points out that a not insignificant minority of Americans said that targeting civilians is at least somewhat justified — a proportion that might have been lower if the word “terrorism” had been used to describe targeting civilians, I suspect.

However, Americans are much more divided on whether the military is sometimes justified in targeting and killing civilians. Muslim Americans overwhelmingly reported it is “never” justified, but the only other group where over half of respondents held that view was for non-believers/agnostics. A solid majority of Protestants, Catholics, and Mormons, and a slim majority of Jews, said that it is “sometimes” justified for the military to target civilians:

The full report includes data on a wide variety of indicators of political engagement and perceptions of quality of life and the future. Consistent with the graphs above, Muslim Americans have less confidence in the military and law enforcement agencies such as the FBI than all other groups (with non-believers/agnostics have the second-lowest levels of confidence):

One major area of difference is in perceptions of why people in Muslim countries might have unfavorable views of the U.S. Muslims Americans were the only group where a majority (65%) thought that U.S. actions were mostly responsible for such unfavorable views. For every other group, the majority thought that misinformation distribution by media outlets or governments was the major cause of unfavorable views of the U.S.:

Muslim Americans were much more likely than all other groups to believe they have experienced racial or religious discrimination. Interestingly, Muslim Americans were the only group where women were less likely than men to say they are always treated with respect by members of other religious groups:

The report authors suggest this may be partially due to Muslim women who wear hijab being visibly recognizable as Muslims in a way that may lead to negative interactions or comments from others.

However, despite higher levels of perceived discrimination, overall, Muslim Americans had a generally optimistic view of their future in the U.S.; the majority of respondents said they will be thriving in the future, and they were slightly less likely than other groups to believe they will be struggling:

I’ve just posted a few items that stood out to me here. Check out the full report for a much fuller discussion of attitudes toward the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, perceptions about quality of life in the U.S., major sources of self-identification (religion, ethnicity, citizenship, etc.), whether Muslims are loyal Americans, and more.

Cross-posted at Montclair Socioblog.

Peter Berger* takes issue with the phrase “on the wrong side of history.” Mostly, he takes issue with those who use that phrase. Specifically, he refers to proponents of gay marriage who claim that the Defense of Marriage Act is “on the wrong side of history” (or in Berger’s acronym, OTWSOH) The trouble with this statement, Berger says, is that “we cannot know who or what is on the right side.”

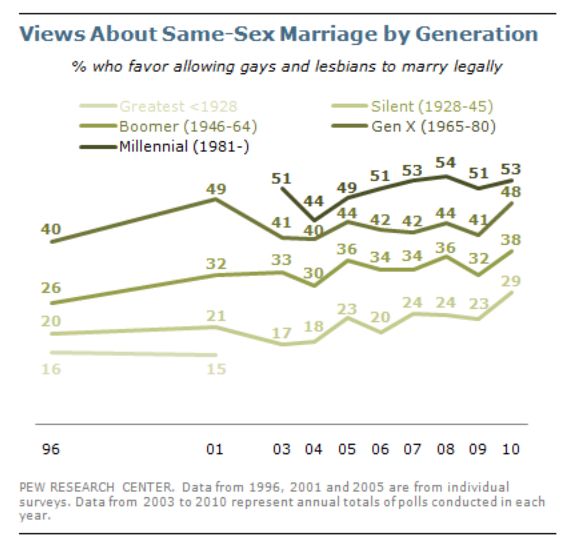

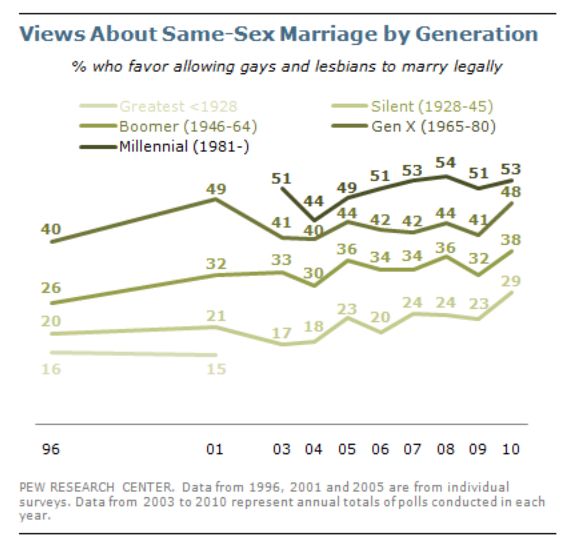

Berger is correct (though he doesn’t offer much explanation) because the history that people are referring to hasn’t happened yet. The history of OTWSOH is the future, and we can’t know the future. However — and here’s where Berger is wrong — we can make a pretty good guess about some things that will happen, at least in the short-run future. We can look at the trend — Americans becoming more accepting of gay marriage — and predict that the trend will continue, especially when we see that the young are more accepting than the old.

But beyond the short-run, who knows? It’s possible that the values, ideas, and even facts that are right today will, decades or centuries from now, be wrong. So it may turn out that at some time in the future, people will think that gay marriage is a plague on civilization, that human slavery is a pretty good idea, that Shakespeare was a hack, and that Kevin Federline was a great musician.

The trouble with asking history, “Which side are you on?” is that history doesn’t end. It’s like the possibly true story of Henry Kissinger asking Chou En Lai about the implications of the French Revolution. Said the Chinese premier, “It’s too early to tell.”

At what point can we say, “This is it. Now we know which side history is on”? We can’t, because when we wake up tomorrow, history will still be rolling on. Duncan Watts, in Everything Is Obvious… Once You Know the Answer, makes a similar point using the historical film “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” The two robbers flee the US and go to Bolivia. Good idea? Since we know how the movie ends — that sepia freeze frame — we can safely say, “No, bad idea.”

But if we had stopped the movie twenty minutes earlier, it would have seemed like a good idea. The vindictive lawman and his posse were about to find and kill them. A few minutes later in the film, Bolivia seemed again like a bad idea – it was a miserable place. Then, when their robberies in Bolivia were easy and lucrative, it seemed again like a good idea. And then, they got killed. Butch was 42, Sundance 31.

But history is not a movie. It doesn’t end. So at least for the long run, the OTWSOH argument claims certainty about what is at best speculation. It says, “We know what will happen, and we know that we are on the right side of history, and those who are not with us are on the wrong side of history.” Some religious folks make similar claims not about history but about God. “We are on God’s side,” they say, “and those who disagree with us are against God.” They tend to populate the political right. The OTWSOH argument, Berger says, “comes more naturally to those on the left,” mostly because that is the side that is pushing for historical change. The two sides are indulging in a similar fallacy — knowing the unknowable — a fallacy which, to those who don’t share their views, makes them appear similarly arrogant.

————————

* Yes, this is the same Peter Berger whose Social Construction of Reality (co-written with Thomas Luckman), published forty-five years ago, has an important place in sociology’s relatively short history.

HT: Gabriel Rossman

In my Sociology of Gender course I talk about how gender conformity isn’t simply a matter of socialization, but often a response to active policing by others. Single women usually avoid having too many cats, for example, not only because they’ve been taught that too many cats sends the wrong signal, but because they may be called a “cat lady” by their friends (a joke-y slur suggesting that she is or will be a batty old spinster). Or her best friend, with her best interests in mind, may discourage her from adopting another cat because she knows what people think of “cat ladies.”

People who find community in subcultures that are seen as “alternative” to the “mainstream” often feel like they are freed of such rules. But these subcultures often simply have different rules that turn out to be equally restrictive and are just as rigidly policed.

A recent submission to PostSecret, a site where people anonymously tell their secrets, reminded me of this. In it a lesbian confesses that she hates cats. Because of the stereotype that women love cats, the “cat lady” stigma may be lifted in lesbian communities. This lesbian, however, doesn’t feel freed by the lifting of this rule, but instead burdened by its opposite: everyone has to like cats. So she feels compelled to lie and say that she’s allergic.

Related, see our post on a confession, from another lesbian, about suppressing the fact that she’s really quite girly.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Cross-posted at Scientopia.

A couple of days ago I posted a video about stereotypes of Native Americans in video games, including the Hot Indian Princess. Though the video discussed video games specifically, these tropes are common in other area of pop culture as well. Dolores R. sent in a great example. Over at Beyond Buckskin, Jessica Metcalfe posted about the 2011 Caribana Parade in Toronto. This year the parade theme was Native America, including various sections such as Amazon Warriors, Lost City of the Aztecs, Brazilian Amerindians…and Tribal Princesses. Here’s a Tribal Princess costume provided by one band, Callaloo (it’s now sold out).

A commenter on Metcalfe’s post takes exception with criticisms of these costumes and the parade theme, saying,

[This is a] celebration of historic alliances between African Diaspora peoples and Native peoples. In New Orleans, the tradition was a specific response to racist laws that placed Native and other POC communities in a common frame of reference. This tradition is almost 200 years old among Caribbean/Diaspora people in North America…you are making a tremendous mistake by attacking a part of Afro-Caribbean culture as if this was the same as an expression of White/Euro privilege.

So the argument is that this can’t be problematic cultural appropriation or propagation of the sexualized Indian Princess trope because it is part of an event meant to celebrate and recognize the histories and cultures of groups that have themselves been the target of discrimination and political/cultural exclusion. Certainly there is an important cultural and historical context there that, the commenter argues, distinguishes these costumes from, say, the current fad of “tribal” clothing in fashion.

And yet, that argument seems to discursively claim a right to represent Native Americans in any way without being subject to criticisms of stereotyping or cultural appropriation. For instance, the Apache were not a Caribbean tribe (though the Lipan Apache moved far into southeastern Texas by the late 1700s, coming into regular contact with Texas Gulf tribes). Does this sexualized “Apache” costume, as imagined by non-Apaches and sold to the general public, differ greatly from other appropriations and representations of Native American culture and identity as fashion statement?

This feels a little like a different version of the “But we’re honoring you!” argument used in efforts to defend Native American sports mascots — that any concern the viewer has is only due to their lack of understanding of the reason for the depiction of Native Americans, not because that depiction might be, in fact, problematic.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Cross-posted at Ms. and Jezebel.

In a previous post I’ve argued against framing a preference for boy children as “culturally Asian.” New data from Gallup, sent in by Kari B., shows that this preference is alive and well among Americans, at least among young men. While women are most likely to have no opinion and about equally likely to prefer a girl or boy, men are significantly more likely to prefer a boy. This preference is strongest among younger men, but still present among men over 50. Whereas women become increasingly indifferent with age and, secondarily, begin to prefer girls.

The editors at CNN note that, since children are mostly born to young people, and indifferent women may bend to men’s preferences, new sex selection technologies threaten to create a gender imbalance in the U.S.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.