This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Luxembourg Agreement, the resulting agreements from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, commonly known as the Claims Conference. The meeting, held just six years after the Holocaust, negotiated tens of billions of dollars in compensation for survivors of the Holocaust, implemented the following year. Each year, the Claims Conference continues to support survivors in dozens of countries around the world. Just last month, the German government pledged another $1.2 billion in funding, including funds explicitly for Holocaust education for the first time.

The staggering level of support from the German government is in line with the horrors perpetrated by the Nazi government between 1933 and 1945. The Claims Conference, while clearly unable to atone for the past, is an attempt by the German government to answer to crimes committed against European Jews under the Nazi regime. On a recent trip to Berlin, I was reminded that signs of this culpability extend all the way down to the streets, where memorials, placards, and other public history displays make clear the role of the National Socialist government in perpetrating the Holocaust.

But while these memorials to the Holocaust ensure that it can never be ignored or forgotten, not all of German history is on public display. There is a story that is conspicuously absent; Germany’s role as a colonial power. The country’s colonial aspirations began even before it gained overseas territories—through merchants who profited off slave labor in other European colonies. It wasn’t until 1884 when the Berlin Conference established the rules for the European colonization of Africa, that the newly formed German Empire established colonies in East and West Africa and the South Pacific. Like their European counterparts, German officials brutally exploited its colonies. Many of the hallmarks of genocidal oppression elsewhere in African colonies could be found in Germany’s colonies as well, including the violent campaigns of retaliation against tribes asserting independence, most notably the 1904-1907 genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples in what is now Namibia. The legacies of German colonialism run much deeper than what can be presented in a blog article, but they still reverberate across the African continent and Germany today.

The German government has accepted responsibility for its colonial crimes, but only somewhat. In May 2021, Germany formally apologized for its treatment of the Herero and Nama peoples, officially labeling its actions as genocide in a statement read by then Foreign Minister Heiko Maas:

We will officially call these events what they were from today’s perspective, a genocide. In doing so, we acknowledge our historical responsibility. In light of Germany’s historical and moral responsibility, we will ask Namibia and the descendants of victims for forgiveness.

In December, the agreement was finalized. In addition to a formal apology from the German government, Namibia will receive more than a billion dollars in aid meant to support Namibia’s infrastructure and public services over the next three decades, which amounts to just under $37 million in funds annually. While the funds appear low, Namibia’s Human Development Index is ranked 139th out of 191 nations, meaning there is a great need for support in the country.

The apology has significant symbolic value and aid for Namibia is much-needed, but I couldn’t help but notice the absence of acknowledgment of Germany’s colonial past in its public history. Berlin’s Tiergarten, which features Holocaust memorials to the Persecuted Homosexuals Under National Socialism and the Roma and Sinti, still includes a statue of Otto von Bismark, the architect of the Berlin Conference. These histories are seemingly at odds with each other and are representative of a country willing to confront the horrors of one past while ignoring another. It’s important to remember that like the Holocaust, Germans of the colonial period would have been exposed to colonialism directly; it wasn’t restricted to overseas territories. Many Africans settled in Germany and, in some cases, even married white German women. However, the experience of Afro-Germans and those in the former colonies don’t seem to be a part of mainstream discourse from the German state.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

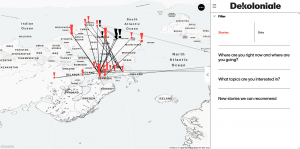

In light of this erasure, several groups across Germany are working to raise the profile of the country’s colonial past in the public consciousness. Located in Berlin, the organization Dekoloniale “tests how a metropolis, its space, its institutions and its society can be examined on a broad level for (post-)colonial effects, how the invisible can be experienced and the visible can be irritated.” In so doing, the organization aims to shift the public discourse away from the history of the oppressors to the story of the victims. Some of its work has included the exhibition Looking Back, organized in conjunction with the Treptow Museum. When the museum wanted to revisit the problematic 1896 colonial exhibition in Berlin, Dekoloniale stepped in, helping organize an exhibit that tells the story of the more than 100 African and Pacific Islanders sent to Germany to serve as a human zoo. For me, a particularly astonishing project is its mapping project, connecting the stories of Afro-Germans with Berlin and former German African colonies, bringing the story of the city’s ties with colonialism home.

In Hamburg, Afro-German activists have opened Arca – Afrikanisches Bildungszentrum, an African-focused library, helping to fill a need they felt public libraries would not and providing a cultural hub. The library itself is housed in a former prison (and before that, military barracks) that’s now being used as an artist commune. It’s one of a number of education centers opened across Germany showcasing Black, Afro-German, and Afro-diasporic perspectives and resources. Coming from the United States which incarcerates its Black population at a staggering rate, the symbolism of a former prison now housing an organization that celebrates African & Black identity cannot be missed.

Despite the many groups working across Germany to raise awareness of its colonial past, it’s an uphill challenge. For instance in Berlin, attempts to rename M-Street (M being a racial slur commonly used during the colonial past) have been rebuffed by residents, echoing a similar unwillingness to rename sites across the Twin Cities (see the debate around Bde Maka Ska and, more recently, Historic Fort Snelling). The street name remains in place, despite continued efforts. In Hamburg, the city’s Speicherstadt district, a UNESCO world heritage site, is receiving millions of dollars in reinvestment in an effort to turn the area into a tourism destination. In spite of the city’s stated goal to create an inclusive space, many of the buildings in the area will now feature the names of European colonial explorers like Columbus, Vespucci, and Marco Polo. These names tie back to a glorified history of European exploration that Hamburg no doubt wants to connect itself to, but do not reflect the diverse population of the city today and serve to reinforce the legacies of colonialism.

I wrote several years ago after the disappointing vote of Rep. Ilhan Omar on the Armenian genocide that recognizing one genocide doesn’t preclude acknowledging another. I can’t shake a similar feeling I have after my two weeks in Germany. The memorials, displays, and exhibitions across Germany serve as an important reminder to never forget the horrors of the Holocaust but also stand in stark contrast to the largely absent public memory of colonial history. I went to Germany expecting to examine how the Holocaust can serve as a catalyst to publicly present other difficult pasts but I left with the impression that many of the challenges we have in representing the legacies of colonialism in Minnesota are similar in Germany. It became clear that while in some instances Germany can serve as the prime example of a country reckoning with its difficult past, its lack of colonial awareness, at times bordering on denial, shows that it’s essentially no different than many other former colonial powers.

Note: This trip was part of the “Building a Diverse and Inclusive Culture of Remembrance (DAICOR)” fellowship, a project hosted by the Heinrich Böll Stiftung in Washington, DC, and CulturalVistas and funded by the Transatlantic Program of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy.

Joe Eggers is the Interim Director of the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies.

Comments