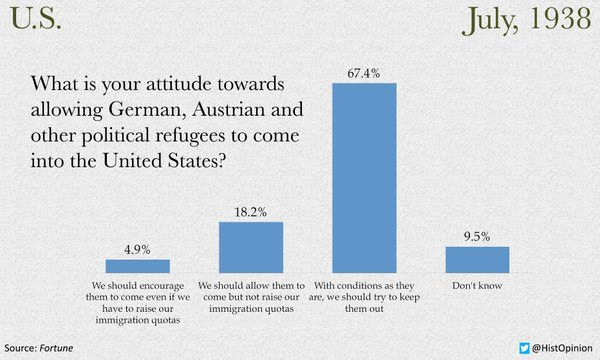

The Twitter account @HistOpinion recently reminded us of the prevailing opinion on raising the immigrant quota for refugees who were fleeing Nazi Germany. Two-thirds of the respondents polled by Gallup’s American Institute of Public Opinion in July 1938 agreed with the proposition that “with conditions as they are we should try to keep them out.”

The Twitter account @HistOpinion recently reminded us of the prevailing opinion on raising the immigrant quota for refugees who were fleeing Nazi Germany. Two-thirds of the respondents polled by Gallup’s American Institute of Public Opinion in July 1938 agreed with the proposition that “with conditions as they are we should try to keep them out.”

Comparisons to the Holocaust and the events that led to it have become commonplace when we examine our current events. Although historical events and contexts always have distinct features that make them unique and thus hard to compare, analogies can indeed provide valuable insight into and perspective on the reality in which we are immersed. This is clearly the case for present-day attitudes toward refugees, particularly in the United States. The number of resettled refugees whom the United States has pledged to receive is dismal in comparison with Canada and most European countries. In terms of percentages, the situation is even worse. And immigration restrictions may get even tighter in response to a state of public opinion shaped by the xenophobic language of presidential candidates in the aftermath of the Paris attacks. Here, denigration of an entire group – defined by ethnicity or religion – and identification of the group as a threat also echo the discourses of the historical period we often consider in this newsletter (both in Europe and in the United States, with the wave of racism, prejudice, and ignorance surrounding Japanese Americans during World War II).

Analogies that bridge past and present are also pertinent to the discussion of the long inaction vis-à-vis the atrocities perpetrated by the Islamic State. For more than two years, ISIS has committed war crimes, crimes against humanity with respect to civilians, and genocide against religious minorities in the territories under ISIS control. The international community has a moral and legal responsibility to protect the victims of these crimes – and the upcoming 67th anniversary, on December 9, of the UN Genocide Convention is an explicit reminder. However, it seems that plans for a coordinated operation against ISIS, involving the possible elimination of its stronghold in Syria and Iraq, are taking shape only now, after its terror has struck the heart of Europe.

Refusal to admit more refugees and passivity in the face of genocide seem to be recurring themes across historical periods. What the past teaches the present will always be a disputed matter. But we will certainly draw a correct lesson from the past if we now endeavor to “keep out” the incendiary language of hatred, fear, and suspicion.

Alejandro Baer is the Stephen Feinstein Chair and Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. He joined the University of Minnesota in 2012 and is an Associate Professor of Sociology.

Comments