Between 1975 and 1979, the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), also known as the Khmer Rouge, fundamentally transformed the social, economic, political, and natural landscape of Cambodia. During this time as many as two million Cambodians died from exposure to disease, starvation, or were executed at the hands of the state.

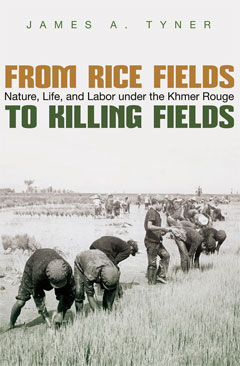

The dominant interpretation of Cambodian history during this period, known as the Standard Total View (STV), presents the CPK as a totalitarian, communist, and autarkic regime seeking to reorganize Cambodian society around a primitive, agrarian political economy. Under the STV, the victims of the regime died as a result of misguided economic policies, a draconian security apparatus, and the central leadership’s fanatical belief in the creation of a utopian, communist society. In short, according to the STV, Democratic Kampuchea, as Cambodia was renamed, constituted an isolated, completely self-reliant prison state. My publication From Rice Fields to Killing Fields: Nature, Life, and Labor under the Khmer Rouge (Syracuse University Press, 2017) challenges the standard narrative and provides a documentary-based Marxist interpretation of the political economy of Democratic Kampuchea.

Communism, according to Marx, was necessary to overcome the alienated life that typified capitalism. This, I argue, was a central concern of the CPK. However, what the CPK actually brought about was anything but a socialist or communist society, but not for lack of trying. I do not doubt that many members of the CPK were committed to what they believed Marxism entails; that there was a concerted effort to bring about a socialist revolution in preparation for an eventual communist society. However, I also maintain that notwithstanding their attempts to establish and defend socialism and to move toward communism, they could not and did not install a communist structure as the prevailing social organization of production. Rather than erecting a non-exploitative system, the CPK merely replaced one form of exploitation with another. Indeed, the CPK reaffirmed a system of production for exchange, thereby negating its own philosophical premise. Quite simply, I argue that the CPK—similar to the former Soviet Union and other so-called ‘communist’ or ‘socialist’ governments—installed a variant of state capitalism.

State capitalism provides the theoretical foundation on which subsequent interpretations of Democratic Kampuchea must be built. Consequently, From Rice Fields to Killing Fields sits alongside previous scholarship that has reinterpreted other so-called ‘socialist’ or ‘communist’ forms of government. In Democratic Kampuchea, I find that a variant of state capitalism similarly emerged in practice while rhetorically CPK cadre spoke incessantly of their own, unique form of Marxism. Workers under the Khmer Rouge remained waged-workers—albeit with a twist. Likewise, the fundamental social relationship between those who owned the means of production (i.e. the CPK as ruling elite) and those denied access to the means of production (i.e. the workers) remained intact.

Ultimately, From Rice Fields to Killing Fields contributes in two principle ways. First, I contribute specifically to our understanding of the Cambodian genocide, namely by providing insight into the material practices that contributed to large-scale violence. For it is my contention that Cambodia’s genocide was the consequence not of the deranged attitudes of a few tyrannical leaders nor of a pervasive hatred toward certain groups. Instead, the violence was structural, the direct result of a series of ill-fated political and economic reforms that were designed to accumulate capital rapidly: the dispossession of hundreds of thousands of people, the imposition of starvation wages, the promotion of import-substitution policies, and the intensification of agricultural production through forced labor.

Second, I contribute to those literatures that have addressed forms of ‘actually existing’ socialism. Here, my concerns extend beyond the specific study of Democratic Kampuchea to address more broadly the dialectics of political philosophy and state form within the context of genocide. Employing an historical-materialist approach, my analysis of Khmer Rouge political economy speaks to deeper questions of ‘Third World’ development, communist revolutions, social movements, and anti-colonialism. It is a mistake, therefore, to view the Cambodian genocide in isolation, as an aberration or something unique. Rather, the policies and practices initiated by the CPK must be seen in a larger, historical-geographical context. Throughout the decades of the Cold War, numerous colonies achieved independence and attempted to remake their political economies. In turn, many of these embryonic countries would be typified by heavy-handed state intervention, state-led industrialization, the nationalization of resources, and anti-imperialist and nationalist fervor. As a former colony and newly independent state, Democratic Kampuchea embarked on a path that was well trod by its Asian and African colleagues, including the aforementioned policies of import-substitution, dispossession, and agricultural-led industrialization. Crucial therefore is to consider why, in Democratic Kampuchea, these economic reforms led to genocide, for satisfactory answers will remain elusive if we fail to position the Cambodian genocide within its proper historical and geographical context.

James A. Tyner is currently Professor of Geography at Kent State University. He received his PhD in Geography from the University of Southern California. Professor Tyner’s research interests include genocide, mass violence, political economy, and Marxism. He is the author of 15 scholarly monographs and over 100 articles and book chapters.

Comments