Dr. Barbara Weissberger is an emerita professor in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Spanish and Portuguese Studies. Next month, she will be presenting her work at the Blood Libel Then & Now: The Enduring Impact of an Imaginary Event conference in New York City.

The Edict of Expulsion of all unconverted Jews that Queen Isabel and King Fernando issued in April of 1492 ended more than a millennium of co-existence between Christians and Jews in the Spanish kingdoms. Between 1391 and 1413 that often fragile co-existence began to unravel when real and threatened violence against Jews caused a massive wave of conversion to Christianity, creating a diverse group known as conversos. Prior to the conversions, blood libel accusations against Jews in Spain, unlike in the rest of Europe, had been exceedingly rare.

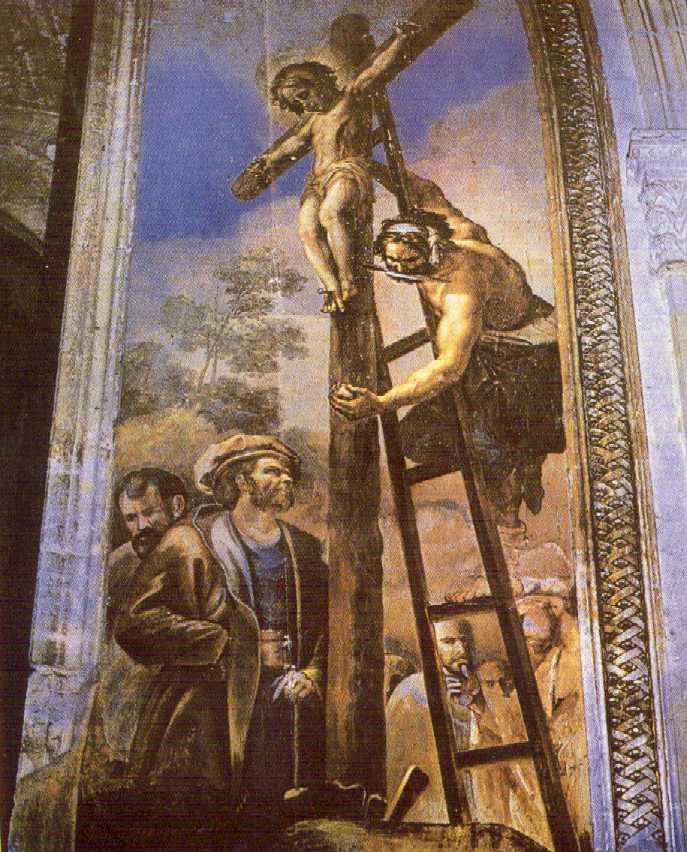

The conversos varied widely in their religious beliefs and practices, from those who were devout Christians, to those who combined beliefs and practices of both Judaism and Christianity, to those who held no religious beliefs at all. But unlike Jews, conversos fell under the jurisdiction of the Inquisition, instituted by Papal decree in 1478 to eradicate heresy. It quickly created a climate of fear and denunciation between so- called “Old” and “New” Christians that set the stage for the spectacular blood libel accusation that is the subject of my presentation: the case of the Santo Niño de La Guardia or Holy Child of La Guardia. In 1487-88, a group of Jewish and converso neighbors from two villages near Toledo were arrested by the Inquisition, accused of kidnapping, torturing, and crucifying a Christian boy. No child was ever reported missing; no body ever found. Nevertheless, after a long trial, six conversos and two Jews were found guilty and burned at the stake in an auto-de-fe on November 16, 1491. Modern scholars maintain that these events were instrumental in the royal decision just a few months later to expel Spain’s Jews. The testimony of the accused and other trial documents in this trumped-up case reveal both the complex daily interaction of Christians and Jews living under the scrutiny of the Inquisition and the Inquisition’s determination to read coexistence as a threat to the unity and security of the emerging nation. Isabel and Fernando, engaged in a long war of succession, were highly susceptible to the insistence of Inquisitor General Tomás de Torquemada that expelling the Jews would eliminate social and political tension by imposing religious unity. The political appropriation of the La Guardia myth persisted up to the twentieth century and the dictatorship of Francisco Franco and his ideology of National Catholicism.

Barbara Weissberger has written extensively on gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and sovereignty in Medieval and Renaissance Spanish literature, and is considered a leading feminist scholar in the field of Hispanomedievalism. She is currently working on a book-project, entitled Anti-Semitism and Nationhood in Spain: 1490-1945.

Comments