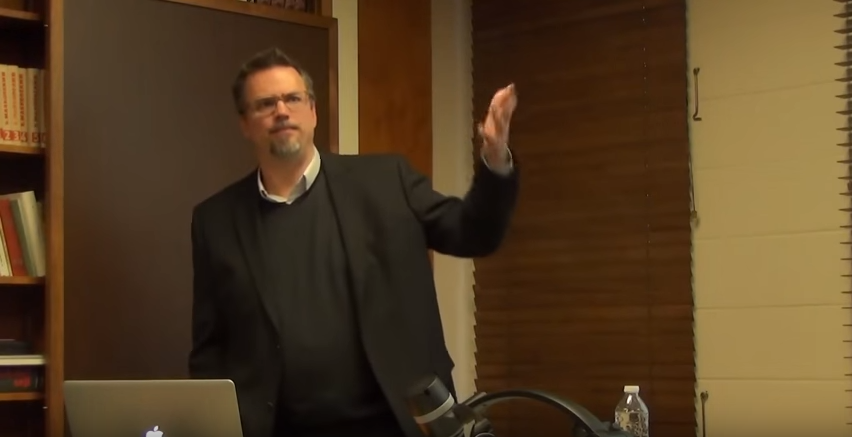

This is the second half of a two part interview with Dr. Adam Muller from the University of Manitoba. CHGS interviewed Dr. Muller after his November presentation on campus in which he highlighted the Embodying Empathy project, a collaborative project at the University of Manitoba that will bring Canada’s residential schools alive with an immersive digital experience.

This is the second half of a two part interview with Dr. Adam Muller from the University of Manitoba. CHGS interviewed Dr. Muller after his November presentation on campus in which he highlighted the Embodying Empathy project, a collaborative project at the University of Manitoba that will bring Canada’s residential schools alive with an immersive digital experience.

If you’d like to get caught up, you can find the first half of the interview here.

What are some of the unique challenges you have experienced using cutting edge technology in a medium that isn’t traditionally associated with it?

It is probably worth pointing out that increasingly museums and commemorative sites of all kinds have been turning to digital technologies in the hope of creating ever-deeper and more rewarding visitor experiences for some time now. Recently, for example, USC’s Shoah Foundation announced that it had begun work on its “New Dimensions in Testimony” project, which seeks create digital holograms of Holocaust survivors that users of the foundation’s testimonial archive can interact with. The initial rendering of survivor Pinchas Gutter is technically quite impressive, and it gestures towards the more immersive and dynamically interactive computer modeling that we’re undertaking in our project. The thing is, for all the investment that’s being done on representations of this kind, the jury is out on whether or not such digitally mediated interactions actually enhance users’ understanding of or capacity to care about others’ suffering, at least over the medium and longer term. This is something Embodying Empathy is looking closely at: whether or not the “immersive turn” in museum curation actually facilitates increases in empathy, and thus a propensity to engage in transformative social action. We’re working with a team of social psychologists to help evaluate the empathy levels of users of the EE storyworld. This has required us to take a closer look at what empathy is and how it works, and specifically at how it might be engaged (or not) by certain features of a digital design. Partly because of its location at the intersection of a large number of distinct academic and technological discourses and procedures, this moral-psychological evaluative element of our project is proving especially challenging, particularly for a humanist like myself but also for older non-academic members of our team with a relatively limited understanding of the potential of emerging technologies and the specifics of social-scientific methods and debates.

There are also considerable risks to our undertaking, not the least of them the possible secondary traumatization of users of the storyworld intimately exposed to viscerally horrifying depictions of the application of coercive force. We discussed with our Indigenous partners the need to withhold or avoid representations of certain forms of physical violence for fear of doing damage to those experiencing Embodying Empathy. However, while acknowledging our concerns, both survivors and intergenerational survivors have been very clear that they want us to remain as truthful and direct as possible when representing IRS experiences. For too long, they have told us, these experiences were hidden away or denied, and thereby allowed to prolong the damage done to identities, families, and communities. Acknowledging and (as insiders, not outsiders) making sense of the damage done by the IRS requires the rejection of earlier regimes of secrecy that the TRC and its resulting archive have done so much to challenge. Where exactly we will draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable forms and subjects of representation, though, remains to be determined.

There’s a perception in the United States that the relationship between the Canadian government and indigenous people is much better than here. What are your thoughts and has your work had impact on your perspective?

It is hard for a Canadian like myself not to be struck by what seems like almost a dead silence on Indigenous issues in American official and popular discourse. This stands in marked contrast to the prominence given to Indigenous issues in Canada, not just with respect to the work done by the IRS Truth and Reconciliation Commission, but in relation to many other aspects of Indigenous history and life more generally. I find the contrast most pronounced politically. We in Canada have just been through a federal election campaign during which the case of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, Indigenous education, northern development and resource rights, treaty rights and land claims, the quality of life of Canada’s Métis people (i.e. those of mixed Indigenous and European ancestry), and the 94 calls to action made by the TRC in its final report were widely discussed and in different forms incorporated into the platforms of all of the political parties vying for power. Justin Trudeau, our new prime minister, has placed Indigenous issues at the forefront of his administration, and just this past December publicly declared that “never again in the future of Canada will students be told that [the historical mistreatment of the country’s Indigenous population] is not an integral part of everything we are as a country and everything we are as Canadians.” There is a prevailing social and intellectual consensus that about this he is correct. By contrast, in the surreal spectacle comprising this year’s American presidential campaign, nothing to my knowledge has been said by any of the candidates from either of the two major parties that suggests Indigenous concerns are or need to be a priority, or indeed that they even exist. Indigenous people barely seem to register in the lived present of the American cultural imaginary; when they are visible at all (as in the recent film Revenant, for example), they show up nostalgically, as traces of the historical past. Viewed not just in but as the country’s past, Indigenous people in America are denied any political currency. When reflecting on the causes and consequences of this disempowerment, I am often reminded of something that the British historian Peter Burke once presciently observed: “It is often said that history is written by the victors. It might also be said that history is forgotten by the victors. They can afford to forget, while the losers are unable to accept what happened and are condemned to brood over it, relive it, and reflect on how different it might have been.”

The Holocaust is now a part of global memory. The residential school system is little known to even many Canadians. Has your team considered the potential for your project creating a new shared memory among Canadians of the residential schools? If so, what kind of impact has that had?

It is true that the country’s Indian Residential School system is something that Canadians are still learning about, notwithstanding the nearly seven year-long effort by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) to bring the story of the genocidal harms done in the country’s residential schools to light. Even after national events staged and broadcast on Canadian news media from coast to coast, the collection of more than 7000 IRS survivor testimonies most of which are now available through the recently-founded National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), a wide variety of primary, secondary, and post-secondary educational initiatives, and various academic and public commentaries and debates, there continues to be a general lack of awareness of the IRS and their lingering negative effects. Going into Embodying Empathy we knew of course that settler Canadians lacked this awareness. What has been surprising to realize is the extent to which relatives and descendants of IRS survivors also have a great deal to learn. Survivors have often not wanted to share the specifics of their lives in residential schools with family and community members. Some were so damaged by their experiences that their lives ended violently and prematurely, leaving them no real chance to impart reliable accounts of what they had undergone.

It is true that the country’s Indian Residential School system is something that Canadians are still learning about, notwithstanding the nearly seven year-long effort by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) to bring the story of the genocidal harms done in the country’s residential schools to light. Even after national events staged and broadcast on Canadian news media from coast to coast, the collection of more than 7000 IRS survivor testimonies most of which are now available through the recently-founded National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), a wide variety of primary, secondary, and post-secondary educational initiatives, and various academic and public commentaries and debates, there continues to be a general lack of awareness of the IRS and their lingering negative effects. Going into Embodying Empathy we knew of course that settler Canadians lacked this awareness. What has been surprising to realize is the extent to which relatives and descendants of IRS survivors also have a great deal to learn. Survivors have often not wanted to share the specifics of their lives in residential schools with family and community members. Some were so damaged by their experiences that their lives ended violently and prematurely, leaving them no real chance to impart reliable accounts of what they had undergone.

Embodying Empathy seeks to fill in some of these blanks, and is relying on extensive and ongoing consultations with IRS survivors and intergenerational survivors to help determine which gaps matter most, to identify relevant experiences to share, and to determine the design parameters of our IRS “storyworld.” We have created a highly consultative and interactive “participatory design” methodology to realize our virtual IRS in a way that gives our Indigenous partners a real say in what the resulting project looks like and is made to do. By giving up ownership of key elements of our project, as well of any resulting technology that is created, we hope to make it possible for the storyworld to provide an intimate and richly nuanced account of the experience of being a child exposed to neglect, starvation, corporal punishment, humiliation, and rape.

Any hope of creating a shared memory of Canada’s IRS, and through the experience of that sharing to foster a morally and politically transformative form of empathy (understood as a kind of doing and not just a quality of feeling), depends crucially on this intimacy and trust. Even when settler Canadians are aware of some of the facts of the country’s Indigenous history, often what they know has been selected and interpreted “from without” by non-Indigenous historians and educators who haven’t taken the time, or lack the wherewithal, to view things from an Indigenous perspective. Along with the NCTR, with which Embodying Empathy has formally partnered, we aim to redress this externality by linking victims of and secondary witnesses to Canada’s IRS in shared experiences of forced assimilation. We hope that via this sharing Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians may together come to a clearer understanding not just of Indigenous suffering but of what constitute appropriate forms of reconciliation and redress. The resulting “imagined community” will, we hope, end up being more humane, inclusive, and just.

Joe Eggers is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, focusing his research on cultural genocide and indigenous communities. His thesis project explores discrepancies between the legal definition and Lemkin’s concept of genocide through analysis of American government assimilation policies towards Native Nations.

Comments