Genocide is a familiar topic to Germans. Today, it is almost impossible to visit Germany and not confront remnants of the darker chapters of the country’s history. Germans interact with and recognize a variety of tangible reminders of the crimes committed by the Third Reich. Countless memorials stand as physical evidence of a violent “past that will not go away”—a past that a majority of Germans publically acknowledge should not go away.[1]

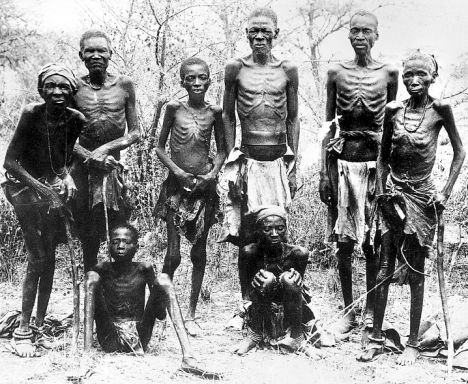

But what about Germany’s other genocide? What place does its memory have in German society today? Between 1904 and 1908, German colonial soldiers carried out the first genocide of the twentieth century in what is now the present-day African state of Namibia (German Southwest Africa).[2] This systematic campaign against Herero and Namaqua peoples—regarded by some scholars as the “Kaiser’s Holocaust”—claimed the lives of over 100,000 men, women, and children through starvation, imprisonment, exile, and murder. German colonial leaders’ impetus for the genocide arose during the so-called Herero-Namaqua Aufstand (Herero-Namaqua Uprising), which began in January 1904 when Herero leaders revolted against the German administration in Southwest Africa. The Namaqua joined the campaign several months later.

In June 1904, Kaiser Wilhelm II appointed General Lothar von Trotha as commander of Germany’s small colonial Schutztruppe (protection force) and charged him to put an end to the rebellion. After a series of inconclusive military engagements throughout the summer, Trotha issued a proclamation in October 1904 that permitted German soldiers to kill Herero peoples indiscriminately. Today, according to the United Nations Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Trotha’s order would constitute a declaration to commit genocide:

I, the great general of the German soldiers, send this letter to the Herero people. Herero are no longer German subjects. They have murdered, stolen, cut off the ears and noses and other body parts from wounded soldiers, and now out of cowardice refuse to fight. . . . The Herero people must leave this land. If they do not, I will force them to do so by using the great gun [artillery]. Within the German border every male Herero, armed or unarmed, with or without cattle, will be shot to death. I will no longer receive women or children but will drive them back to their people or have them shot at. These are my words to the Herero people.

Historians often refer to Trotha’s declaration as the Vernichtungsbefehl (annihilation order). Over the next three years, German troops oversaw the extermination of approximately 85 percent of the Herero (over 100,000 people) and 20 percent (10,000 people) of the Namaqua populations. They also expropriated the Herero and Namaqua’s land for German settler-colonists, killed or forced their leaders into exile, and seized their cattle, which constituted their primary source of wealth. After the genocide, German colonial leaders created an apartheid state in Southwest Africa, passing bans on “mixed-marriages” and constructing Eingeborenenwerften (“native settlements”). The colonial administration also led efforts to increase the number of white women in the colony and to “racialize” migrating peoples from the British Cape Colony.

Though the Herero-Namaqua Genocide is well-known among historians of European colonialism and genocide studies, it is largely unfamiliar to many—perhaps even most—Germans today. While the Holocaust has become a distinct marker of German identity in the years since the Second World War, the Herero-Namaqua Genocide remains a minor chapter in the violent saga of European colonialism in Africa. The closest official acknowledgement of the massacres came twelve years ago, when Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, Germany’s then development minister, apologized for the mass killings and called Trotha’s program an act of “genocide” while on a trip to Namibia in 2004. Though Wieczorek-Zeul’s remarks received considerable attention both in Germany and Namibia, the German government did not adopt her position.

Twelve years later, German leaders finally appear to be changing their stance. The Frankfurter Rundschau reported in July 2016 that an official document prepared by the German government “for the first time recognized the Herero and Nama massacre as a genocide.” Chancellor Angela Merkel’s office also confirmed that Germany would formally apologize to Namibia and surviving descendants of the genocide. Sawsan Chebli, a spokesman for the German foreign ministry, added that “The federal government has been pursuing a dialogue with Namibia on this very painful history of the colonial era since 2012.” “We seek a common policy statement on the following elements: a common language on the historical events and a German apology and its acceptance by Namibia,” she concluded in the same interview.

Namibians have long called for an official apology from Germany. Since the country’s independence from South Africa in 1990, Namibia’s leaders have also sought reparations for decedents of Herero and Namaqua families affected by the genocide. In 2011, Namibians protested in large numbers outside Windhoek after Germany returned human remains that colonial officials had taken to conduct anthropological research in Leipzig and Berlin. German leaders had hoped that returning the skulls would send a positive signal of reconciliation. Instead, it only helped to remind Herero and Namaqua families that their demands for repartitions and land reclamation had largely fallen on deaf ears in Europe. Today, the Herero make up nearly 10 percent of Namibia’s total population. A sizable percentage are still trying to reclaim the land that German white farmers seized from their ancestors following the Herero-Namaqua Genocide.

The German government’s decision to identify General Trotha’s conduct in colonial Namibia as genocidal is both significant and long overdue. Though German officials confirmed that they will not pay any reparations to Namibian families, this pronouncement nevertheless represents an important first step toward confronting its colonial past. By commemorating the memory of those who perished at the hands of German soldiers in Namibia, Chancellor Merkel’s administration has started what one hopes will be an ongoing effort to teach people about the Herero-Namaqua Genocide and its on-going consequences in Namibia today. It also extends more public attention to a crime that has been in the shadows for too long outside of southern Africa.

The plight of peoples forced to live under the oppressive yoke of European colonial governments remains an untold story for a significant number of people in the Global North. This reality is perhaps even more pronounced in Germany, given the country’s violent history on the European continent during the first half of the twentieth century. While it is understandable that many Namibians would expect some measure of reparations, especially decedents of those families who were killed in the massacres, German leaders have at least helped bring more attention to the issue by calling the crime for what it is—genocide. As more people learn about Germany’s colonial history in Namibia, one can hope that Herero and Namaqua communities and their continued struggles will receive more international attention.

Few people today can argue that Germany has not confronted its Nazi past. Unlike the vast majority of capital cities in Europe and North America, Berlin’s central avenues, parks, and museums are filled with clear reminders of a time that most would understandably like to forget. Instead of trying to hide this history, however, German leaders long ago embraced the Holocaust as a means to prevent future acts of genocide around the world. By confronting its genocide in Namibia, Germany, finally, has opened the door for more dialogue, research, and reconciliation in the future.

[1] Ernst Nolte first used the phrase “the past that will not go away” in an effort to shift scholarly attention away from the Holocaust and Nazi era. See Ernst Nolte, “The Past That Will Not Go Away,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (6 June 1986).

[2] In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, European imperial authorities called the Southwest Africa. After German colonization in 1884, the colony was recognized as German Southwest Africa.

Adam Blackler is an Assistant Professor of History at Black Hills State University in Spearfish, South Dakota. He recently finished his Ph.D. in the History Department at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. His research explores how colonial encounters in colonial Namibia led Germans to fashion an imperial image of the Heimat ideal. He has presented his research at numerous national and international conferences, including the German Studies Association, the Freie Universität zu Berlin, and the Transatlantic Doctoral Seminar organized by the German Historical Institute.

Comments