Film, since its inception, has played a significant role in capturing history. It has given us ways to explore events in the past while contemplating the present. Art (it would seem) is ahead of politics, especially in matters of examining the painful realities of World War II in Eastern Europe. In recent years there has been a dangerous trend in Poland and Hungary in revising history to fit a political narrative.

Both Poland and Hungary have been trying to balance Democracy and the rise of right wing political parties, who are determined to use the Holocaust to rewrite historical narratives to create nationalistic pride, directly contradicting their past and present. Poland and Hungary along with Ukraine, Lithuania and Latvia, are all experiencing revisionist movements. Historian John Paul Himka believes part of the problem is how these once double occupied countries (by Germany and the Soviet Union) dealt with false historical narratives or “myths” they were told under post-war Soviet occupation, once they were free of Communism. Himka states in their hurry to join the West, they did not take the necessary time and care to explore their wartime roles, allowing for a division between memory and fact.

Poland has been making news after Polish President Andrzej Duda signed controversial legislation which criminalizes any mention of Poles “being responsible or complicit in the Nazi crimes committed by the Third German Reich.” The legislation is very strong on reserving the harshest penalties (of up to 3-year prison sentence) for those who refer to Nazi-era concentration camps as “Polish death camps.” The only exemptions from the law is scientific research and artistic work about the war.

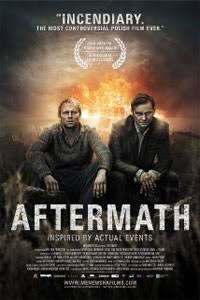

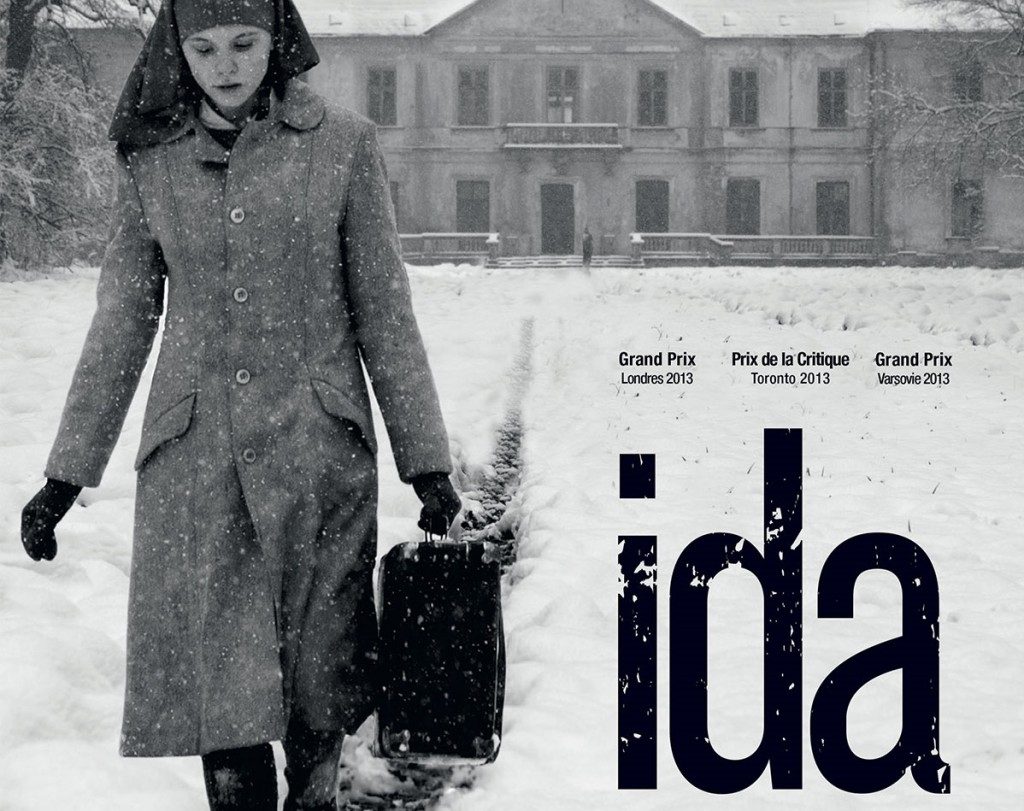

It is interesting that art is exempted, but one must wonder who will determine what is or is not art, or what will be acceptable to the Polish government. The right factions of the government have already shown their hand in how they received the two critically acclaimed films Aftermath and Ida, which deal with the controversial issue of the complicity of Poles in the destruction of their Jewish populations. Both films were labeled anti-Polish, with claims that they inaccurately portrayed Polish actions during WWII.

It is interesting that art is exempted, but one must wonder who will determine what is or is not art, or what will be acceptable to the Polish government. The right factions of the government have already shown their hand in how they received the two critically acclaimed films Aftermath and Ida, which deal with the controversial issue of the complicity of Poles in the destruction of their Jewish populations. Both films were labeled anti-Polish, with claims that they inaccurately portrayed Polish actions during WWII.

Aftermath was controversial because it was based on historian Jan Gross’ work Neighbors, which explores the murder of the Jews of Jedwabne by the town’s Poles in July of 1941. The films deal with the myth that it was the Germans who had killed the Jews. The massacre has always been a controversial topic since the release of the book in 2001, and Gross has been the subject of ongoing outrage as he has been repeatedly denounced by Polish right-wing scholars and politicians for defaming the Polish people. Ida, originally less controversial, became targeted after it won an Academy Award for best foreign film in 2015. In 2016, it was televised on Polish TV with a 12-minute government sanctioned documentary defaming the film.

The two films have lead the way to a new movement in Eastern European Holocaust cinema, which examines the actions of the bystanders and the benefactors of the crimes against Jews. Both Aftermath and Ida dig up the past by recovering the secrets buried in unmarked graves across Eastern Europe, exposing the living more so than the dead for as the graves yield their secrets. Those who hoped to bury their crimes in the past must now deal with them in the present, with tragic results.

The two films have lead the way to a new movement in Eastern European Holocaust cinema, which examines the actions of the bystanders and the benefactors of the crimes against Jews. Both Aftermath and Ida dig up the past by recovering the secrets buried in unmarked graves across Eastern Europe, exposing the living more so than the dead for as the graves yield their secrets. Those who hoped to bury their crimes in the past must now deal with them in the present, with tragic results.

The latest film to tackle this theme is 1945, a Hungarian film released in 2017, directed by Ferenc Török, based on the short story “Homecoming” by Gábor T. Szántó. The film definitely takes its cues from Aftermath and Ida, sharing both films’ quest for the truth through the lens of 1930’s Hollywood horror and art house film. In 1945, two unknown Jewish men visit a small Hungarian town in the aftermath of World War II. The appearance of the two men sends the town immediately into panic as they reflect on their guilt while rationalizing their behavior towards the missing Jews of the town, whose belongings, homes and businesses they have possessed. Like, Aftermath and Ida, the townspeople are haunted by their actions, but in 1945, burial has a much different meaning. Filmed in black and white, the film also feels like an old western, with tensions that build towards a showdown between the strangers and the townspeople.

It would not hurt for Eastern Europe to look to modern Germany, who after decades of self-reflection and dealing with their past, have accepted responsibility for their actions during World War II. Certainly, this is not easily done, and of course the ghosts of Hitler and the Third Reich will always loom over Germany. Nevertheless, if a country is to thrive, it must examine and learn from its past, admit its wrongs, and accept responsibility before they become the thing they valiantly claim to have fought against. Until then, we will have to hope that more filmmakers in these countries will continue to dig up the past and reveal the truth so that people can remember and honor the dead, as well as truly be able to bury the past in a way that allows them to move forward.

Jodi Elowitz is the director of education at the Center for Holocaust and Humanity.

Comments