After the arrival of thousands of U.S. veterans, the long-standing Dakota Access Pipeline protests culminated in a small victory on Sunday when President Obama ordered the Army Corps of Engineers halt work on the pipeline. Victories like the one on Sunday and the President’s previous order in September have been overlooked, though. The BBC has called the protests the largest gathering of Native Americans in a century; why then do they feel so invisible? What accounts for the lack of media coverage at Standing Rock?

In October, the Daily Intelligencer interviewed Amy Goodman, host of the independent news site Democracy Now!, speculating how it is possible that “in this oversaturated age for a mass-protest movement to fly under the radar” on “the battle over the building of the $3.8 billion Dakota Access pipeline,” and Goodman suggested a larger, systemic problem:

“I dare say the lack of coverage may be because this is a largely Native American resistance and protest. This is an under-covered population generally.”

The invisibility of Native Americans as a people, their sovereign lands, and sacred burial sites (a significant element to the Dakota Access pipeline story) is illustrated by Energy Transfer Partners’ proposed construction map for the Dakota Access pipeline. The map both minimizes sovereign territory, but also denies the existences of sacred land—it does, however, clearly depict a potential threatening environmental hazard along the Missouri River, the sole water supply of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

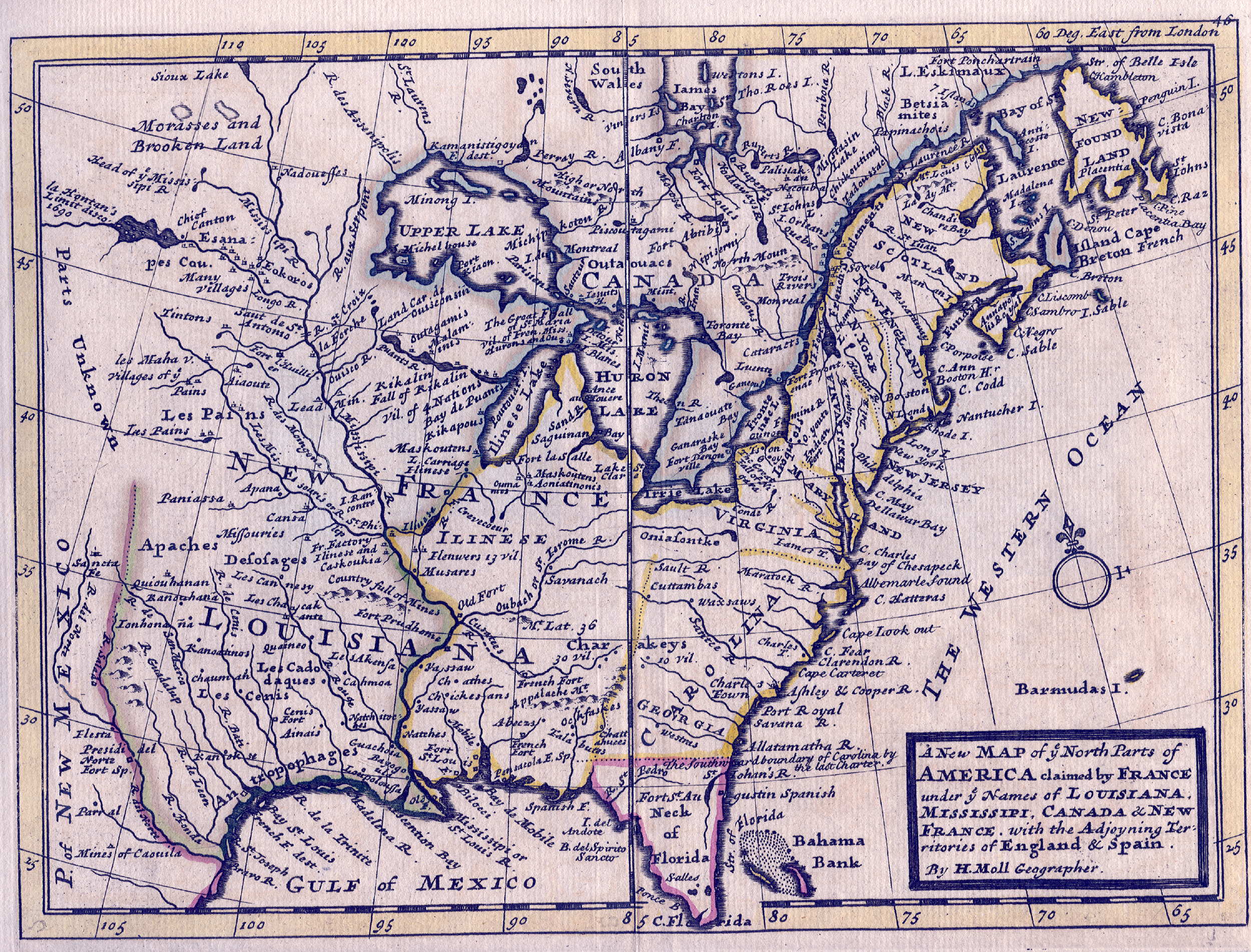

Such maps of exploitation by non-Native interests stand against an extensive backdrop of colonial settler expansion of the ‘American frontier’ and the historical erasure of the indigenous population. It is here where Euro-American ideology of land, its use, and claims to ownership —predicated on the Doctrine of Discovery, a 19th century Euro-Christian concept used to validate the taking of indigenous lands by colonial powers —present a sharp contrast with that of Native American cultures.

Creating Maps and Erasing Place

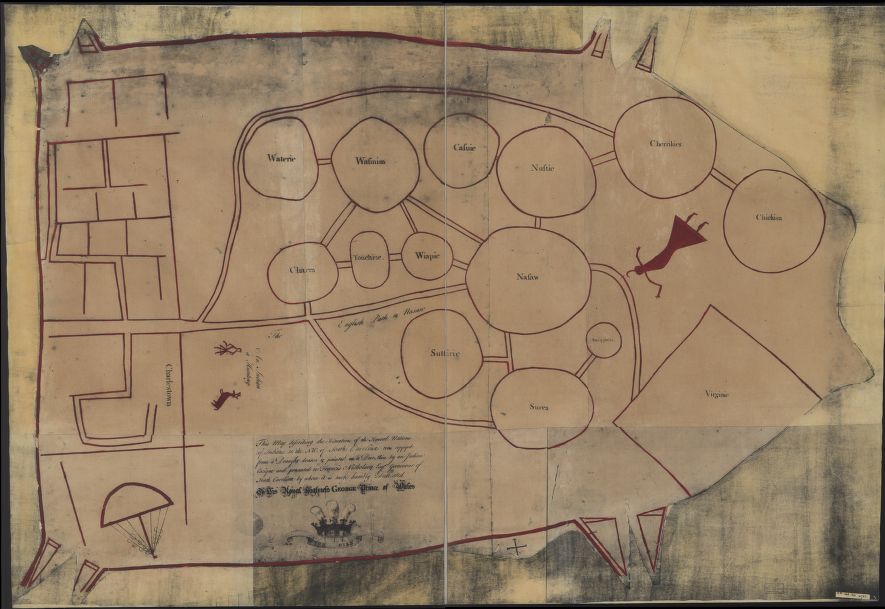

Maps themselves, of course, can represent places of physicality but they are also cultural, conceptual, and invested in meaning and value. The following series of maps illustrate this point. British maps created during the colonial period (1600-1700s) provide a stark contrast to the infamous Catawba “Deerskin map” from 1721—one of the only maps made by the indigenous people of the Americas.

As can be seen in the 1624 map of Virginia—created by John Smith who would later lead the British colony of Jamestown—native figures are represented along the upper left corner and right side of the map. Euro-colonial cartography of this time stands out by the sharply defined separations of land claims, detailed boundaries with place names, and the treatment of “unclaimed” space as “unknown” despite contrary accounts indicating the known presence of indigenous tribes west of “known” territory (Map 2). Contrast these with the map created on deerskin by a Catawba leader.

First, it’s important to note that such a map was an official document—a lens with which an understanding could be built and not imposed—presented by a Catawba community leader to the Governor of South Carolina to communicate with European authorities the particular relationships and perspectives of the tribes near the new settlements. We see a network of villages connected by trails and delineated by circles, which symbolize southeastern Native unity in political, genealogical, and ceremonial bonds. The trails connect the Native groups to the European settlers in both Charleston (rectangular grid) and Virginia (plain rectangle) whose representation is angular and sharp, similar to their own mapmaking.

Significantly, this map does not necessarily tell the traveler how to get from “Point A to Point B”, but rather, conveys social and political relationships that embody a shifting and dynamic landscape; one that is shaped by both past and present experience. Spatial presentation here is not limited to universalizing or creating precise landscape illustrations for the purpose of defining set boundaries and ownership.

Standing Rock, the Pipeline and Maps

Through the recent developments at Standing Rock, the ‘unfinished’ project of the American frontier and its colonial expansion through the Doctrine of Discovery is once again made clear. The boundary-defined and legitimated landscape that we have come to know as the United States was established through an imperial ideology of ownership and domination, defining what constituted real and unreal, empty and occupied. As we have seen with the projected Dakota Access Pipeline, Native Americans continue to be separated from and invisible to the land they inhabit in Euro-American maps, enabling genocide. From this perspective, cartography has been used as a tool of violence for Euro-colonialists, and continues to be part of the capitalistic culture in pushing the American frontier in more vertical endeavors.

Brieanna Watters is a Ph.D. student in sociology at the University of Minnesota. Her research interests are in mass violence, collective memory and post-colonialism in the United States.

Comments