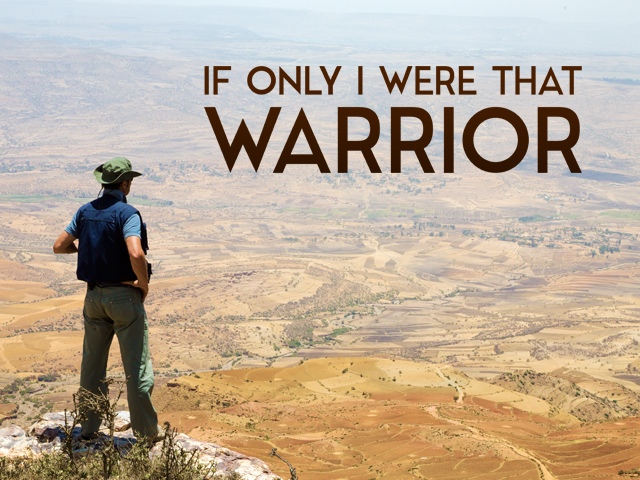

On Saturday, February 20th the Italian Cultural Center of Minneapolis & St. Paul presented If Only I Were That Warrior as part of their annual Italian Film Festival followed by a moderated discussion. In the film, director Valerio Ciriaci examines Italy’s brutal attempts to colonize Ethiopia in 1935 through the lens of the 2012 erection of a monument dedicated to Rodolfo Graziani. The monument, located in the Italian town of Affile, reignited the tense politics surrounding Graziani’s involvement in the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and its legacy today.

On Saturday, February 20th the Italian Cultural Center of Minneapolis & St. Paul presented If Only I Were That Warrior as part of their annual Italian Film Festival followed by a moderated discussion. In the film, director Valerio Ciriaci examines Italy’s brutal attempts to colonize Ethiopia in 1935 through the lens of the 2012 erection of a monument dedicated to Rodolfo Graziani. The monument, located in the Italian town of Affile, reignited the tense politics surrounding Graziani’s involvement in the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and its legacy today.

Rather than focusing his film solely on the crimes committed by Graziani, known as the Butcher of Ferran for his massacre of civilians in Libya, and the Italians during the invasion and subsequent occupation, Ciriaci chose instead to highlight the monument as a means to convey the difficult, and largely unexplored, legacy of Italy’s  attempted African conquest. The monument itself was initially proposed as a symbol for the Unknown Soldier and used public funds for its construction. When the federal government learned that it was being dedicated to Graziani, the funds were revoked, but Affile’s mayor privately funded some of the project despite the federal government’s condemnation of the memorial. It is not unusual for monuments in Italy to be funded by public-private partnerships, but there was no partnership in Affile’s conscious omission of the monument’s intent. Ciriaci uses this opportunity to showcase the lingering pride in Graziani and the Mussolini-era fascist government that continues to exist today across much of Italy.

attempted African conquest. The monument itself was initially proposed as a symbol for the Unknown Soldier and used public funds for its construction. When the federal government learned that it was being dedicated to Graziani, the funds were revoked, but Affile’s mayor privately funded some of the project despite the federal government’s condemnation of the memorial. It is not unusual for monuments in Italy to be funded by public-private partnerships, but there was no partnership in Affile’s conscious omission of the monument’s intent. Ciriaci uses this opportunity to showcase the lingering pride in Graziani and the Mussolini-era fascist government that continues to exist today across much of Italy.

The film follows three people– Mulu Ayele, an Ethiopian refugee in Italy who invites viewers into the country’s protests of the Graziani monument, Nicola DeMarco, an Italian-American New Yorker and grandson of an early Italian Ethiopian settler actively organizing the monument protests, and Giuseppe Debac, an Italian coordinator of a UN development project in Ethiopia.

It’s perhaps Debac’s narrative that best exemplifies the complicated relationship Italians have with their past. When he is introduced, Debac seems as if he will be the pragmatic UN worker with insight into the horrific Italian occupation as we job shadow him through Ethiopia. However Debac ends up representing the complexity of the Italian identity and the lack of acceptance of Italy’s role as he shares his fascination with the past, stopping at Italian cemeteries among the countryside, pointing out the Italian infrastructure built during the occupation, all while saying that he feels “the presence of the Italians and never feels alone” on his country assignment.

Graziani is a complex figure in Italian history. After World War II, he was indicted as a war criminal by the UN, in part for his actions in Ethiopia. Despite this, he has several supports across Italy. Ercole Viri, the mayor of Affile, deems Graziani “a proven hero” and local business owners defend the monument as “due recognition to a local historical figure.” The memory of Italy’s fascist past is made even more complicated because of the resettlement of thousands of Ethiopian refugees following the country’s civil war. Ayele conveys this difficulty as she organizes protests against the fascist monument. She is also campaigning for the monument and park to be rededicated to the victims of Graziani’s occupation of Ethiopia as well as Libya.

After the movie, a moderated discussion was held by Achmed Wassie of KFAI’s Voices of Ethiopia program and Michael Senay, the former president of the mutual benefit association at the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Minneapolis and whose parents were witnesses to the Italian occupation of Ethiopia. Mr. Wassie and Mr. Senay had the difficult task of answering questions from a diverse audience at the film which attracted many from the Ethiopian community. Emotions ran high during the discussion: some commended the Italian Cultural Center for bringing this film to Minneapolis; others criticized the organization for not being stronger advocates of the issue. One audience member passionately critiqued the film for not showing more of Ethiopia’s struggle since the Italian occupation. These criticisms from the audience demonstrate the strained relations that continue to exist between Ethiopians and Italians even in the Twin Cities.

While I can sympathize with the feedback, I was impressed the Italian Cultural Center featured this film and provided a venue for discussion over a topic that is both rarely focused on and critical of Italian political views and the revisionist history that is being spread. Having spent time as part of a consulting team for a UNESCO project in northern Ethiopia, I could easily see the Italian influence in the area. City centers are still called piazzas, areas subject to the Italian occupation had more paved roads and bridges, and stuccoed buildings stood in contrast to the more traditional Ethiopian construction. I worked on a 17th century castle complex which Italian soldiers made their residence and we could visibly recognize the modifications and intrusive alterations made on the site. Despite these influences, any Ethiopian I worked with would proudly tell you that Ethiopia has never been occupied. It is a proud part of their identity and cultural heritage. Without films like If Only I were that Warrior, this troubling history could easily continue to go unexplored.

Allison Suhan graduated from the University of Minnesota with an MS in Heritage Preservation in 2015. During her graduate studies, she spent several weeks assisting the Ethiopian government restore the Fasilides Castle complex in Gondar. Her primary research focus is funding strategies for Italian heritage sites, where she spent a semester studying as an undergraduate student.

Comments