In November, the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies welcomed Dr. Adam Muller from the University of Manitoba to discuss his upcoming project, which creates a virtual First Nations residential school. Dr. Muller is part of the Embodying Empathy project, which seeks to create a digital immersive experience for educate visitors about the settler-colonial interactions at Canada’s residential schools. The project is also exploring whether immersive representations can bridge the empathetic distance separating victims from secondary witnesses to atrocity.

In November, the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies welcomed Dr. Adam Muller from the University of Manitoba to discuss his upcoming project, which creates a virtual First Nations residential school. Dr. Muller is part of the Embodying Empathy project, which seeks to create a digital immersive experience for educate visitors about the settler-colonial interactions at Canada’s residential schools. The project is also exploring whether immersive representations can bridge the empathetic distance separating victims from secondary witnesses to atrocity.

Dr. Muller is Associate Professor of English at the University of Manitoba (Canada). He specializes in the representations of war, genocide and mass violence, human rights, memory studies, critical theory, cultural studies, and analytic philosophy.

CHGS followed up with Dr. Muller to learn more about his innovative project. You can find a recording of the original presentation here. This is part 1 of our conversation.

Could you tell us about how the concept for the virtual museum was initiated?

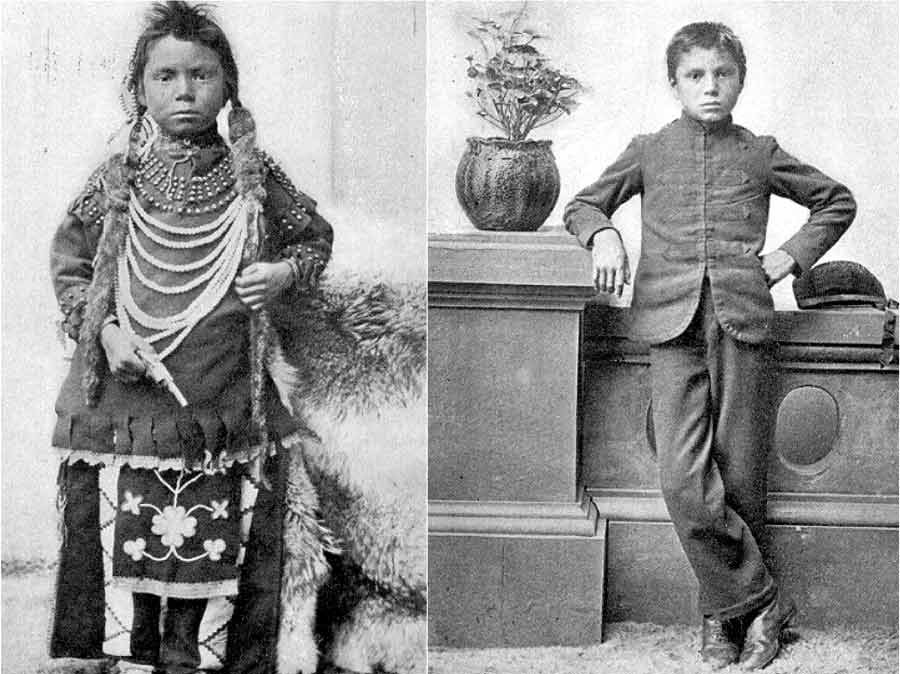

In 2011, during the early planning and design stages of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, I was one of three organizers of a lecture series hosted by the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Law entitled “The Idea of a Human Rights Museum.” As part of this series I, along with my colleagues Struan Sinclair and Andrew Woolford, decided to present a talk on some of the thinking behind what the CMHR’s plans to become an “ideas museum” might mean for the representation of Indigenous experiences, most especially those associated with Canada’s Indian Residential School system. Ideas museums depend heavily on technology and not artifacts to create enriching experiences for museumgoers. We were wondering what kinds of technology the museum might use to engage its visitors, and whether or not they’d be well-suited to representing Indigenous experiences of human rights abuses and successes stories. In preparing for our lecture we noted the increasing dependence of museums of all kinds, but especially ideas museums, on various virtual and augmented reality technologies. These included VR headsets and digital overlays of otherwise static exhibitions designed to give museum visitors more information, and richer experiences, than would be available through observation alone. These technologies have been increasingly viewed by museum curators as a good way to connect with to younger audiences already cognizant of VR and AR via their use in digital gaming. We wanted to explore how they might be adapted to the demands of representing traumatic experiences, and were also curious about whether or not more immersivity would translate into an increase in museumgoers’ understanding of historical trauma, as well as enhancements in their capacity to care. We noted that to date the secondary literature remains divided on whether or not such technologies can open people up empathetically to others’ suffering, or else instead contribute to what has been termed “empathy fatigue,” or the erosion of our capacity to feel for others. And so with these issues in view, Embodying Empathy was born as creative, critical, commemorative, and educational project seeking to build and assess the empathetic potential of a virtual and immersive museum-quality representation of a Canadian IRS.

In your presentation, you discussed the successful efforts to get support from survivors of the residential schools. What was their initial reaction to the project and has that changed as it has evolved and taken shape?

From the first we were nervous that what we were thinking of doing would be perceived by IRS Survivors as an attempt to hijack and/or distort their school experiences. We worried that what we wanted to do would seem not merely problematically playful to them (in so far as we were turning their suffering into something plausibly understood as a video game) but offensive. When we began discussing our project publicly, we really didn’t know what to expect in response. We were acutely aware that the core idea for Embodying Empathy was hatched by three non-Indigenous scholars, and we weren’t sure we could explain our belief in the merits of our project in a way that would reassure people all too familiar with the hollow promises and risks more typical of conventionally “extractive” forms of academic research.

We were therefore surprised at (and relieved by) the strong support for Embodying Empathy that we’ve received from a wide range of Indigenous people from the get-go. Survivors have made it clear that they view our work as urgent and necessary, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation views the project as potentially an extremely useful way of making their testimonial archive more accessible, and intergenerational survivors and other members of Indigenous communities have expressed their hope that via our immersive storyworld they may become better informed about the exact nature of the abuses suffered by their relatives. Of course things have been made somewhat easier by our high degree of consultativeness. We have been very careful to involve Indigenous people in our project not as objects of inquiry (i.e. “things” to be studied) but as full research partners actually determining the directions our design and critical inquiry are heading. We actually ended up developing new and very explicit language concerning the fullness of this partnership which we included in our research ethics protocols. In order to maximize the control and oversight of our Indigenous collaborators to our project we have adopted a “participatory design” methodology that requires us to share and modify potentially all of our strategies and results before they are finalized and made public. Thus one of our project’s goals is to empower our Indigenous partners while contributing to contemporary thinking about the appropriate forms and methods of non-extractive Indigenous research. The sincerity of our commitment to this end seems have to inspired the confidence of those whose stories of IRS life we are working to share, as well as our prospective audiences.

The experiences in the boarding schools were wide ranging. How is your team incorporating survivor accounts that vary so greatly from fairly positive memories to extremely traumatic ones?

We have been aware from the outset of the potentially harmful reductions inherent in conceiving of our storyworld as a single, prolonged, trauma-drama. Even though many of the survivor testimonies presented before the TRC focused on negative experiences such as physical and sexual abuse, they also often included reference to positive aspects of IRS life such as moments of human kindness, extraordinary resilience, and hope. This diverse complex of experiences is something actually acknowledged by the TRC in its final report, though critics of the commission continue to point to its conclusions as deliberately and unproductively one-sided. In consultations with our Survivor advisory council, we have come to understand the experience of being a student at an IRS as not one single thing but rather as an unstable patchwork of positive and negative occurrences resulting from the schools’ wider goal of stripping away from Indigenous people their capacity to remain culturally intact, and so dignified and self-respecting versions of themselves. One of the major challenges for us in our attempt to design our storyworld has therefore been how to acknowledge this complexity while not making IRS life seem more horrific, uplifting, or even banal than it really was.

We have been aware from the outset of the potentially harmful reductions inherent in conceiving of our storyworld as a single, prolonged, trauma-drama. Even though many of the survivor testimonies presented before the TRC focused on negative experiences such as physical and sexual abuse, they also often included reference to positive aspects of IRS life such as moments of human kindness, extraordinary resilience, and hope. This diverse complex of experiences is something actually acknowledged by the TRC in its final report, though critics of the commission continue to point to its conclusions as deliberately and unproductively one-sided. In consultations with our Survivor advisory council, we have come to understand the experience of being a student at an IRS as not one single thing but rather as an unstable patchwork of positive and negative occurrences resulting from the schools’ wider goal of stripping away from Indigenous people their capacity to remain culturally intact, and so dignified and self-respecting versions of themselves. One of the major challenges for us in our attempt to design our storyworld has therefore been how to acknowledge this complexity while not making IRS life seem more horrific, uplifting, or even banal than it really was.

In an attempt to limit to a manageable number the experiences we will be representing in Embodying Empathy, we chosen to focus primarily on a single school, the Fort Alexander IRS located near Pine Falls, Manitoba, on land that is now part of the Sagkeeng First Nation. For the most part the members of our advisory council attended this school, though our research (and the testimony taken by the TRC) has revealed considerable overlap in experiences undergone at a wide range of schools across the country. We are also concentrating on experiences of the sort likely to have been undergone from the 1940s to the early 1960s. Residential schools functioned and were staffed and regulated differently at different periods of Canadian history, and we are anxious to incorporate the experiences of former IRS students undergone by a generation that is rapidly declining in health and numbers. Since we are just now entering the design phase of our project, and since our methodology is highly consultative and so dependent on the guidance we’ll receive from various stakeholders and partners, we don’t yet know exactly which experiences will feature prominently in our virtual world.

Stay tuned for the second half of our interview with Dr. Muller, coming next week!

Joe Eggers is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, focusing his research on cultural genocide and indigenous communities. His thesis project explores discrepancies between the legal definition and Lemkin’s concept of genocide through analysis of American government assimilation policies towards Native Nations.

Comments 1

Hidden No More: Our Continued Conversation with Dr. Adam Muller – The Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies — February 17, 2016

[…] If you’d like to get caught up, you can find the first half of the interview here. […]