On December 30, 2020, Argentina’s Senate voted to legalize abortion. This decision found resonance with thousands of activists present outside the national Congress building, waiting, witnessing, and testifying why aborto sea ley, why legal abortion, must be the law. After 12 years of debate – really, after decades of debate in the wider public forum, the news of the official tally in favor of legalization was met by tears of joy, drumming, and dancing in the streets of Buenos Aires. These celebrations were echoed and sustained in the streets and homes throughout Argentina, but also across the wider transnational feminist network, both in physical spaces and in the digital public sphere.

In these final days of 2020, the anthem of Argentina’s feminist movement for abortion access transformed from sea ley to es ley. This was a moment that condensed time and space, moving from “it will be law” to “it is law.” From a projection into a labored-for, hoped-for future, these social movement actors found themselves now able to make a definitive statement on social reality as it now is, a defined present. Es ley, it is law, it is our right, our bodies.

In the course of their fight, for justice, health equity, and bodily sovereignty, activists have articulated various framings of abortion as a human right, as a necessary health service, as embodied resolution, as one piece of the puzzle for labor and economic justice, as part of the prevention of gendered violence, and as the marea verde of feminist activism that continues to sweep across Latin America.

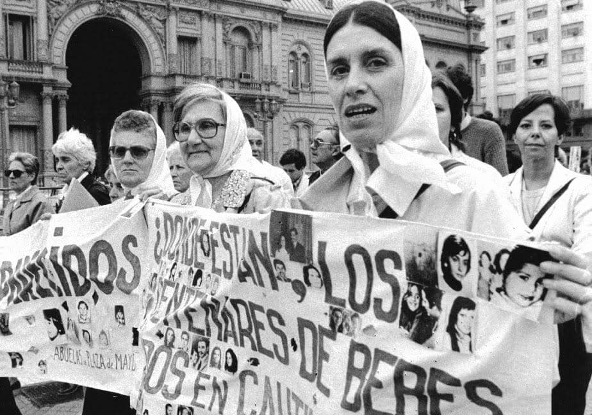

This marea verde (green wave), as the transnational feminist movement in Latin America has come to be known, uses a variety of visual symbols in their activism. One of the most recognizable is the green pañuelo (head-kerchief) introduced by Argentina’s movement for reproductive justice and the legalization of abortion. The pañuelo is a bricolage of political history and contemporary mobilization, repurposing the white head-kerchiefs worn by the Madres and Abuelos de la Plaza de Mayo in their protests against the desaparecidos, the forced disappearance of their children and human rights violations of the state.

The Madres and Abuelas wore their head-kerchiefs in their weekly marches around the central plaza in downtown Buenos Aires, directly outside the presidential mansion, the Casa Rosada. The pañuelo brought the intimacy of the family into the public forum, making an explicitly gendered and very visible statement that expanded the definition of who is a political actor, what mobilization can look like, and which motivations can spur collective action.

With their embrace of the pañuelo, turning it green and wrapping it around necks and wrists as well as hair, Argentina’s contemporary feminist movement expanded the terms of mobilization and the definition of violence once again. It has likewise been transformed into a symbol of protest against gender violence by the Ni Una Menos movement. From their first mobilizations in 2015, Ni Una Menos has worn purple pañuelos in protest of femicide and gendered violence of all kinds, and proclaiming “nos queremos vivas, libres, y sin miedo” (we want them alive, free, and without fear). United by the pañuelo, Ni Una Menos’s work against gender violence overlaps with the goals of the campaign for the legalization of abortion.

In the weeks between the vote in the lower house and the deciding vote in the Senate, feminist groups from around the world sent messages to Argentina’s feminist groups supporting their fight, wearing the distinctly Argentina symbol of the pañuelo, extending the symbol again beyond physical borders. As an expression of inter-movement and transnational solidarity, the pañuelo has circulated across borders, bridging diverse issues, and framing them collectively as issues of collective violence perpetrated by, at best, the negligence of the state and at worst, by the state’s direct action.

With this re-articulation of the pañuelo, activists also make present those who are absent, visible only in the spaces created by their ghosting as victims of state violence, intimate violence, of the violence enforced through the absence of access to sexual and reproductive health services like legal abortion. It calls back to those disappeared by the state during Argentina’s dictatorship of 1977-1983, connecting political violence to reproductive violence. It joins the cry of ¡Ni una menos!, of not one more death of a trans- or cis-woman, bringing together questions of reproduction, gender, and sexuality into new focus.

It connects abortion access to labor rights and poverty, finding the connections between individual experiences of harassment and hunger with collective locations in social structures of inequality. And it gives a logic for connecting access to abortion with the experience of the pandemic, articulating how differential access to prevention and services is undergirded by those same social structures that perpetuate gendered violence.

On January 14, 2021, Ley 27.610 Acceso a la Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo was signed into law by President Fernández. It went into effect on January 24, making Argentina the third country in South America to fully legalize abortion as a fundamental human right of its citizens. This is, of course, only one more step towards reproductive justice in Argentina – the difficult process of putting policy into practice remains. And yet, it is a very large and significant step forward in the march towards gender equity across the continent, across the world.

The marea verde, the green tide, continues to swell with raised fists and pañuelos, in the pursuit of a transversal, feminist future. With its evolution and sustained crescendo as a movement, it carries us to expanded definitions of collective violence and connection across historical and contemporary traumas. And today, in recognition of International Women’s Day, we can continue to bear witness, remember, and imagine an expansive and just future.

Samantha Leonard is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of sociology at Brandeis University, where she is completing her dissertation tentatively titled “Defining Violences: Feminist Movements Against Intimate Partner Violence in Argentina and the United States.” She is also currently a research associate for the “Cascading Lives: Stories of Loss, Resilience, & Resistance” project, directed by Dr. Hansen at Brandeis University and Dr. Kibria at Boston University, and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates and Raikes Foundations. Her interests broadly include culture, social theory, social movements, violence, and race, gender, and class.

Comments