I acknowledge that the University of Minnesota Twin Cities stands on Miní Sóta Makhóčhe, the traditional, ancestral, and contemporary Homelands of Dakhóta Oyáte. The University occupies land that was cared for and called home by Dakota peoples from time immemorial. Ceded in the treaties of 1837 and 1851, I acknowledge that this land has always held, and continues to hold, great spiritual and personal significance for Dakota. By offering this land acknowledgment, I recognize the sovereignty of Dakota, and I acknowledge, support, and advocate for Indigenous individuals and communities who live here now, and for those forcibly removed from their Homelands. I will continue to raise awareness of Indigenous peoples, histories, and cultures in my work, especially within social studies education, and I will continue to work to hold the University of Minnesota accountable to Dakota and other Indigenous peoples and nations. It is my sincere hope that the curriculum project discussed below will serve as a catalyst for recognizing and unsettling settler colonial narratives in social studies classrooms across Minnesota, especially sixth-grade Minnesota Studies classes.

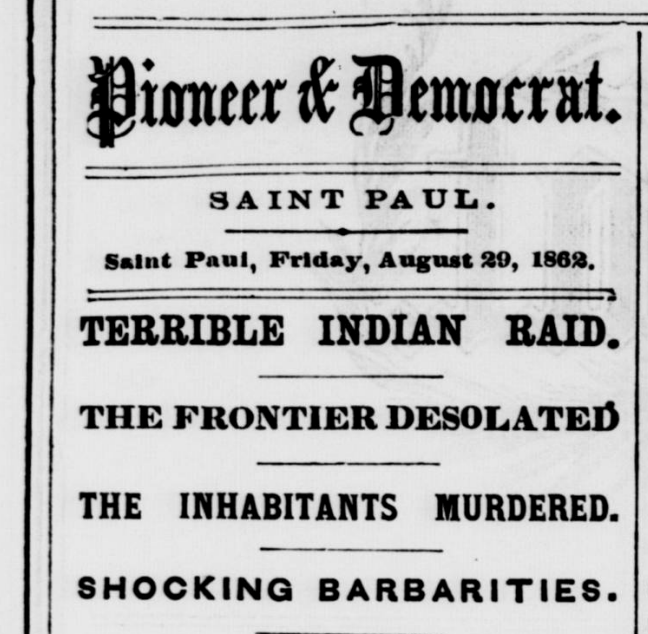

In mid-August of 1862, the Pioneer and Democrat, as short-lived settler newspaper printed in St. Paul, Minnesota ran an article with the headlines:

“Terrible Indian Raid.

The Frontier Desolated

The Inhabitants Murdered

Shocking Barbarities.”

The article, a mix of news and editorial content common in early reporting, stated: “We can no longer shut our eyes to the fact that the Sioux Indians have commenced a war upon the settlements of our own frontier, and have massacred hundreds of men, women, and children.” Such accounts of what would come to be called the “Sioux Massacre” became the first rough drafts of the history of the war. Indeed, one of the earliest published histories of the war, Isaac Heard’s History of the Sioux War and Massacres, published by Harper and Brothers of New York in 1863, draws on reporting from, among other newspapers, the Pioneer and Democrat.

One hundred fifty years later, in mid-August of 2012, the Minneapolis Star Tribune ran a series titled: “In the Footsteps of Little Crow: 150 Years After the U.S.-Dakota War.” One article featured headlines quoting Taoyateduta (often known as Little Crow), a leader of the Dakota during the war:

“‘When men are hungry, they help themselves’

With his people starving and treaty payments too late to help, Little Crow is pushed toward war. A bloody confrontation lights the fuse.”

Such headlines seem to suggest a marked shift, both in terms of language and narrative, in how the U.S.-Dakota War is popularly portrayed, at least within the media.

What might these two articles, written 150 years apart, tell us about how popular narratives and collective memories of the U.S.-Dakota War have shifted over time in Minnesota? Take, for example, the shift from earlier articles that suggest an unprovoked “massacre” of Euro-American settlers to the later recognition of the continued maltreatment of the Dakota, who are ultimately “pushed to war.” Do shifting accounts of the war, as reflected in media reporting, mimic changing public memories and attitudes within the state, especially among non-Indigenous Minnesota’s, or are they simply examples of settler-constructed narratives shifting strategically over time to maintain settler dominance over land and ensure a “settler futurity” for generations to come?

These questions were central to a project led by the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies’ Director, Professor Alejandro Baer , and Research and Outreach Coordinator, Joe Eggers, who, along with a undergraduate and graduate student researchers, gathered and analyzed hundreds of newspaper articles from Minnesota River Valley and the Twin Cities newspapers at 25-year intervals from 1862 to 2012. The aim of the project was to better understand how the U.S.-Dakota War has been remembered over time, with each generation, and space in Minnesota.

Using the rich data from this project, with additional funding from a Minnesota Legacy Grant, and in keeping with the CHGS’s mission of educational outreach, I was asked to think about how the newspapers collected and analyzed during the project might be made available and useful for teachers and students. The result is a curriculum, “From the ‘Sioux Massacre’ to the ‘Dakota Genocide’: Minnesota’s ‘Forgotten War’ in the State’s Newspapers from 1862 to 2012,” which was designed to supplement a study of the U.S.-Dakota War in sixth-grade social studies classes.

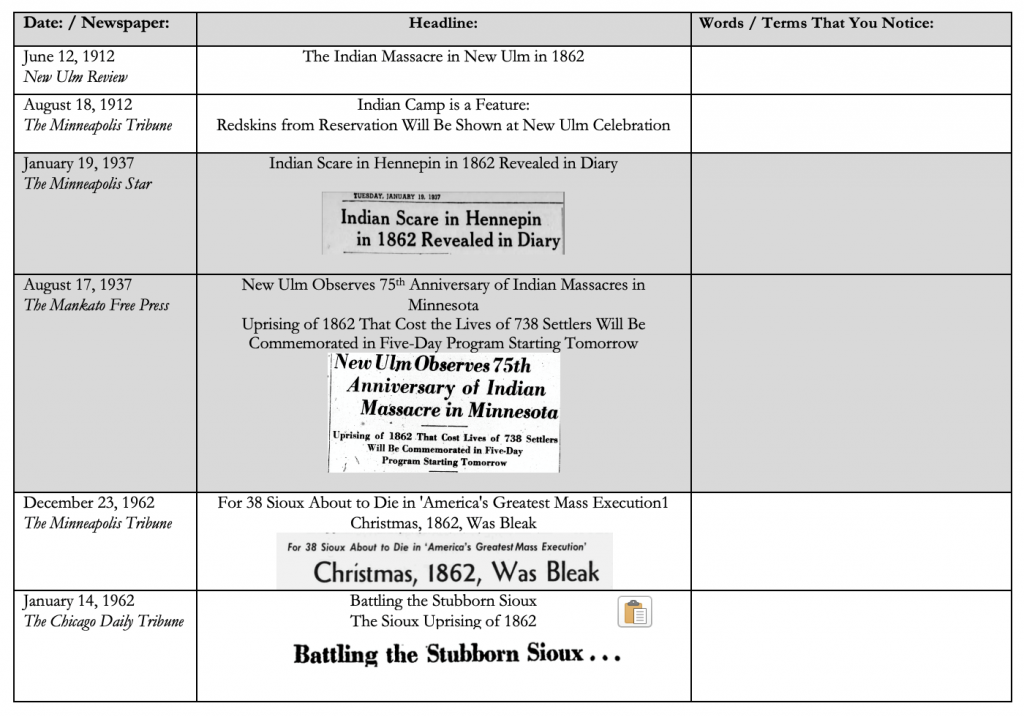

The curriculum is organized around a single-day core lesson plan, which was designed to be taught in one roughly-50-minute class period. This core lesson introduces students to examples of newspaper headlines from the Minnesota River Valley and Twin Cities, allowing them to catalog and analyze how the narratives of the war have varied over time and space.

Additional two and three-day lesson plans offer teachers and students the opportunity to extend the core lesson for deeper content and skills development through reading and analyzing examples of full-length articles and analyzing data form the project in the form of graphs and charts. Each lesson encourages students to engage in an attentive and thoughtful reading of newspaper articles as primary source documents, developing critical media literacy skills.

As I began to work on developing the curriculum, what I was most drawn to was the possibility for “authentic learning,” in which students would construct knowledge through the use of disciplinary-based inquiry that would also have value beyond the classroom. I imagined students doing work – reading and analyzing newspapers to draw conclusions about narratives of the U.S.-Dakota War – which would be very similar to the work that had been done by academics and student researchers at the University of Minnesota. This authentic work, involving qualitative research and analysis, would help them to understand the shifting nature of historical narratives over time.

However, despite the exciting possibilities for teachers and students to engage with this authentic learning, the curriculum should be taken up with a note of caution. First, the lessons, by and large, fail to bring much needed Dakota (and other Indigenous) voices and perspectives into the classroom, often framing the Dakota (and, to a lesser extent, settler) as perpetually static, monolithic, and opposing groups. Additionally, many earlier newspaper articles not only lack Dakota perspectives, but they are also filled with derogatory language, such as “red skins” or “savages,” which, without careful introduction and contextualization, could easily further perpetuate hurtful stereotypes. However, this fairly blatant derogatory language is perhaps less concerning than the more subtle erasure of Indigenous voices and perspectives within the narratives developed within the articles. These newspaper articles, after all, represent a settler archive, where even the more recent articles from 2012 were written by non-Indigenous authors and very often still lack Dakota voices. This provides a challenge for teachers and students to engage with these articles critically and read them not only for what is present but also for what is absent in the reporting and editorializing.

As with any study of history, students studying the U.S.-Dakota War should be pushed to examine sources and narratives critically and continuously ask questions to nuance their understanding of events and peoples. Despite its limitations, examining the shifting settler narratives of the U.S.-Dakota War over time and space within Minnesota may help students better understand the roots of contemporary debates, such as those to rename Historic Fort Snelling or Bde Make Ska, and become more thoughtful consumers of media.

Download the full curriculum: “From the ‘Sioux Massacre’ to the ‘Dakota Genocide’: Minnesota’s ‘Forgotten War’ in the State’s Newspapers from 1862 to 2012”. We are especially interested in hearing about your and your students’ experiences with the curriculum. Send any feedback to George Dalbo at dalbo006@umn.edu.

George Dalbo is the Educational Outreach Coordinator for the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies and a Ph.D. student in Social Studies Education at the University of Minnesota with research interests in Holocaust, genocide, and human rights education. Previously, he was a middle and high school social studies teacher, having taught every grade from 5th-12th in public, charter, and independent schools in Minnesota, as well as two years at an international school in Vienna, Austria.

Comments