Have you ever seen a baton twirler perform? They manipulate a metal stick in magical ways: rolling it between their fingers, tossing it 20 feet into the air, and catching it between their legs or completely blind behind their head. If you have seen a baton twirler, it was likely a young woman in a bedazzled swimsuit-style costume. While it is true that baton twirlers are more often young women and girls, it was not always that way. In fact, much like cheerleading and figure skating, men were the first to twirl, not women.

Baton twirling as we know it today originated in the military where corps leaders and drum majors would spin maces and rifles. The tradition of the twirling drum major is kept alive in The Ohio University’s Buckeye Marching Band (check out the 2017 auditions). A part of Americana since the 1930s, today baton twirlers can most often be seen in football halftime performances and occasionally on parade. Because of the number of twirlers who took up twirling in the years following WWII, the notion that twirling a baton is “girly” persists, helping to shape the stereotype of the effeminate, presumably gay male baton twirler. The persona of the female twirler remains: graceful gals in sparkly costumes and tasseled boots prancing around the gridiron. Baton twirling for men is often stigmatizing because of its association with high femininity: such as beauty pageants like Miss America where it is often satirized.

There is another, lesser known performance arena for baton twirlers, however: competitive baton twirling. Behind the scenes, baton twirling has developed into an athletic event rivaling rhythmic gymnastics, figure skating, and competitive dance. In the US, two organizations dominate: National Baton Twirling Association (NBTA) and the United States Twirling Association (USTA). Approximately 30 countries around the globe host baton organizations, many with individual competitors and teams that compete in world-level Olympic-style events. Given the history of the sport around which they were formed, in the US these organizations are have become increasingly feminized.

Thus, “boys don’t do that” is a script heard by boys who wish to pursue dance, figure skating, cheerleading, and baton. A baton twirler myself, I grew up hearing this phrase to which my response was, “why not?” Nobody seemed to have a clear explanation so I decided to investigate how the experiences of young men in baton twirling to show the impact of cultural scripts associated with gendered organizations. I found that the social costs of participating in a feminized sport leave boys feeling shameful and out of place—singled out for their lack of commitment to sports boys are supposed to play.

Kind of Like Unicorns

In my research where I interviewed men and boys who twirl or once twirled, I found that they stand out when in the limelight because, as one twirler, Hayden, mentioned, guys who twirl are “kind of like unicorns,” rare yet powerful. Even at young ages, male twirlers are aware they are not the norm because so few boys join them in baton classes and competitions. Their numerical minority in a feminized sport places them in unusual circumstances for experiences of advantage and disadvantage. In the realm of competitive baton twirling, the appearance of a boy is cause for excitement. In a rough estimation, I project that there is only one male twirler for every 100 female twirlers—a figure likely very conservative.

There are some benefits to being uncommon like unicorns. Male twirlers easily stand out and receive attention on a crowded competition floor. According to NBTA rules, no matter their skill level, boys do not have to qualify for national-level events whereas girls do in most events. And, it is suspected they are given higher baselines scores to encourage their continued participation. The advantage seems to stop there, however.

In constant comparison to their female counterparts, male twirlers detailed how they are not given the same spaces to twirl and are often relegated to awkward spaces under basketball hoops. They explained to me that they do not feel they receive the same accolades as the female champions with their crowns, banners, and trophies. Additionally, male twirlers are automatically placed in the Advanced difficulty division whereas young women beginning to twirl typically rise through Novice, Beginner, and Intermediate levels before moving into the Advanced category. While this may seem like a benefit, it is discouraging for young male twirlers like Garrett who has competed for only a year may compete against Brad who has been twirling for ten years. Needless to say, their skills are no match for each other.

Male baton twirlers are encouraged by coaches and judges to attach themselves to pieces of masculinity in hopes to remain within the parameters of acceptable masculinity. Male twirlers’ performances challenge notions of masculinity because baton twirling is simultaneously athletic, yet also aesthetic in a way uncharacteristic of sports associated with traditional notions of masculinity. To make up for this, they choreograph fists in their routines, twirl to rock music, and often wear “masculine” colored costumes in blue accentuated with anything from skulls and cross bones to animals, stars, fire, lighting strikes, and super hero emblems.

The Gender of Twirling

Perhaps the optimistic read of the unicorn men who twirl is that they challenge the effeminate image of the baton twirler and offer up a fresh interpretation of baton twirling. In recent years, three male baton twirlers have performed to great applause on America’s Got Talent, one of whom just missed the top ten by placing 11th. Male baton twirlers have also been featured with marching bands at high-profile universities across the country. During football season, fans at games root for the “baton guy,” and get in lines for autograph signings. Across generations, twirlers have performed at World’s Fairs and have been featured on the Ed Sullivan Show.

Internationally, few countries with large populations of people of color compete on a world level (with the exception of Japan) pointing to how baton twirling is a Western sport. Yet, as twirling has spread across the globe, male twirlers have been met with praise indicating that perhaps some of the femininity of baton twirling is limited to American perspectives. For example, at the 2016 World Baton Twirling Federation championships, France competed an all-male team in which they played up their boyband-like sexuality. And, the current men’s world champion, Keisuke Komada, of Japan is a well- respected artist who has pushed the sport to new heights—literally. Baton twirling in the US is a predominately white sport and, in many ways, reflects class stratification and racialized inequalities.

At work here is a gendered organization (the sport of twirling) influencing gender at an individual level (male twirlers).With women increasingly entering male-dominated jobs like coaching in the NFL, men and boys have not equally been encouraged to enter female-dominated spaces with the same fervor. Male baton twirlers, just like female boxers or weightlifters, should be celebrated as gendered inequalities within organizations continue to be challenged.

Trenton M. Haltom is a PhD student in the Sociology Department at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. His research sits at the intersection of masculinities, sexualities, and sociology of the body. He is a nationally recognized competitor, member of Team USA 2015, and a former feature twirler for the University of Nebraska Cornhusker Marching Band. His work on baton twirling has also been featured in MEL Magazine. You can find him at www.tmhaltom.com.

Perhaps the most visually potent symbol of this assumed backwardness of Islam is the headscarf that some Muslim women wear. How emancipated can Muslim women really be, the argument goes, when they have to cover themselves lest they sexually tempt men?

Perhaps the most visually potent symbol of this assumed backwardness of Islam is the headscarf that some Muslim women wear. How emancipated can Muslim women really be, the argument goes, when they have to cover themselves lest they sexually tempt men?

Hey Girl w/ Pen readers! I’m excited to share with you an excerpt of a piece I wrote recently with sociologist, Orit Avishai, on how some evangelical Christians and Orthodox Jews challenge stereotypes about conservative religion and sexuality that appears in

Hey Girl w/ Pen readers! I’m excited to share with you an excerpt of a piece I wrote recently with sociologist, Orit Avishai, on how some evangelical Christians and Orthodox Jews challenge stereotypes about conservative religion and sexuality that appears in

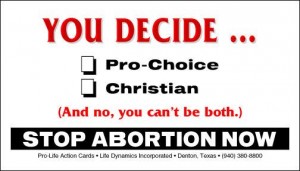

When it comes to anti-abortion activism, sociologist

When it comes to anti-abortion activism, sociologist

I couldn’t decide if I was surprised or not when I read that Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) was protesting Kim Davis. WBC is notorious for their protests, and their targets have ranged from U.S. soldiers killed in combat to country western singer,

I couldn’t decide if I was surprised or not when I read that Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) was protesting Kim Davis. WBC is notorious for their protests, and their targets have ranged from U.S. soldiers killed in combat to country western singer,  While we can’t know who is going to heaven (since righteous living is only a hint that you might be elect, not a reason for it), we can know who is going to hell—or at least some of them. If you aren’t living a godly life, it’s because God hasn’t elected you; and he hasn’t elected you because he hates you, which is his prerogative as your creator. Remember that the elect can’t resist living a righteous life, so the only people left to dwell in disobedience are the damned, those chosen by God for his holy hatred before they were even born.

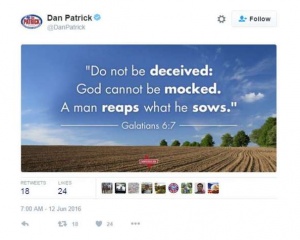

While we can’t know who is going to heaven (since righteous living is only a hint that you might be elect, not a reason for it), we can know who is going to hell—or at least some of them. If you aren’t living a godly life, it’s because God hasn’t elected you; and he hasn’t elected you because he hates you, which is his prerogative as your creator. Remember that the elect can’t resist living a righteous life, so the only people left to dwell in disobedience are the damned, those chosen by God for his holy hatred before they were even born. If religion and sex are in the news, WBC usually weighs in. The Davis case is an example, in WBC eyes, of how Christians have failed to prevent the advancement of the gay agenda by failing to adhere to God’s standards about sexuality more broadly. WBC sees homosexuality as the last sin a culture will accept; by the time we decided to legally recognize gay marriage, we’ve already legalized divorce and remarriage, made adultery commonplace, and legalized abortion. Homosexuality is the last stop on a train we should never have boarded, in this line of thinking. And that is not unique to WBC. The Southern Baptist Convention

If religion and sex are in the news, WBC usually weighs in. The Davis case is an example, in WBC eyes, of how Christians have failed to prevent the advancement of the gay agenda by failing to adhere to God’s standards about sexuality more broadly. WBC sees homosexuality as the last sin a culture will accept; by the time we decided to legally recognize gay marriage, we’ve already legalized divorce and remarriage, made adultery commonplace, and legalized abortion. Homosexuality is the last stop on a train we should never have boarded, in this line of thinking. And that is not unique to WBC. The Southern Baptist Convention

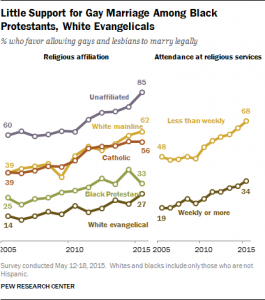

White conservative Protestant evangelicals have been the obligatory homophobes in the political controversy over same-sex marriage in America

White conservative Protestant evangelicals have been the obligatory homophobes in the political controversy over same-sex marriage in America