About a month ago, I found myself embarrassed to sit as the sole faculty member at a table of new members of Sociologists for Women in Society (SWS) – that is, aside from Dr. Mary Bernstein, outgoing SWS president, who led the new member orientation. I was excited to attend my first SWS winter meeting (really, first of anything hosted by SWS), but also embarrassed that I was new already half way to tenure and still “new.” No disrespect meant to the graduate students in that room, but I felt as though I was sitting at the kids’ table at Thanksgiving dinner. And, when it came my turn to introduce myself, I felt as though I was at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting: “Hi, my name is Eric Grollman, and this is my first SWS meeting.” “Hi Eric,” my fellow newbies didn’t actually say, but I could hear in my imaginative and anxious mind.

No Support To Attend SWS Meetings

I went through all six years of graduate school, and then two years in my current position, without ever attending an SWS function. Some years I was a dues-paying member, and some years not. I justified the distance from SWS by identifying as more of a health scholar, and secondly a sexualities scholar – that gender was only tangentially related to my research. It took an encouraging email from SWS Executive Officer, Dr. Joey Sprague, to finally get serious about becoming involved in SWS. Recently, my work as an intellectual activist – particularly on my blog, Conditionally Accepted – has focused on protecting fellow intellectual activists from public backlash and professional harm. As many of those who have been attacked are women of color, it was clear that my efforts were in line with SWS’s mission and many of its initiatives. You-should-get-involved became you-should-attend-the-winter-meeting, which became you-should-organize-a-session-on-this-topic. This was quite a break from what feels like eagerly awaiting opportunities for leadership in other academic organizations!

I’ve studied sexuality and gender, as well as their intersections with race, since I officially declared my major in sociology and minor in gender studies in college. And, I’ve been an activist of sorts since kindergarten, focusing heavily on LGBTQ and gender issues beginning in college. Why did it take me so long to get involved with SWS – a feminist sociologist organization?

Elizabeth Salisbury, Drs. Jodi Kelber-Kaye, Ilsa Lottes, Fred Pincus, Michelle Scott, Carole McCann, and Susan McCully, among others. These aren’t names that are known nationwide (not yet, at least), but they are forever a part of my life. These are professors who were fundamental in the raising of my feminist consciousness, and in feeding my budding activist spirit. They introduced me to Black feminist theory (among other theoretical perspectives), feminist and queer critiques of the media, womanist accounts of herstory, and social justice-oriented research methods. Clearly, I still feel nostalgia for those days of self-exploration, advocacy, and community-building.

Graduate school, unfortunately, was a hard right-turn from my undergraduate training. I chose to pursue a PhD in sociology, assuming it would be easier to get into the fields of gender studies, sexuality studies, or even student affairs with that degree than the other way around. I won’t waste my energy on regretting the decision, but I recognize that it was the first of many compromises I would make to advance my career. Dreams of a joint PhD with gender studies were dashed due to “advice” that I would not be employable. I was discouraged from my fallback plan of a graduate minor in gender studies or sexuality studies because, I was told, one can “read a book” to learn everything there is to know about gender. By the time I selected the topic for my qualifying exam, I knew to select the more mainstream area of social psychology rather than the more desirable areas of sexualities, gender, or race/class/gender/sexualities. Still, I was reminded again that my interests in gender, sexualities, and race were not “marketable” when I proposed a dissertation on trans health. I was mostly obedient as a student. So, I shouldn’t have been surprised by my friends’ surprise that I had been offered a tenure-track position in sociology with a focus on gender and health. I entered grad school open to interdisciplinary study on queer, feminist, and anti-racist issues, utilizing qualitative methods, and tying my research to my advocacy; I left a mainstream quantitative medical sociologist who viewed writing blog posts as a “radical” forms of advocacy.

Would it surprise you that I wasn’t encouraged to attend an SWS meeting in graduate school? Those who were actually involved in SWS did so on their own volition. We were otherwise expected and encouraged to attend the mainstream organization – the American Sociological Association – and perhaps the regional sociology conference as a starting point to “nationals.” It wasn’t encouraged, it wasn’t the norm; and, on the limited funds of a graduate student, I had to be pragmatic about which conferences I attended. ASA won out all through grad school and beyond.

Finally Finding My Feminist Sociology Community

So, back to my first SWS winter meeting. It was amazing, of course. I felt like an academic celebrity, having many people – some whom I knew, many whom I did not – express their appreciation for my blog, Conditionally Accepted. Admittedly, with such visibility as an intellectual activist, there is a lingering twinge of the mentality I was forced to adopt in grad school: “what about my research?” I thought privately. Obviously, these colleagues care about my research, as well. But, I found that the meeting, unlike other conferences I’ve attended, was just as much about research as it was about feminism, activism, and building a community. At what other conference would I feel torn between attending a session on feminist public sociology (hosted by the fine folks at Feminist Reflections) and another on campus anti-racist activism? Certainly not the conferences I’ve been attending over the years.

So, back to my first SWS winter meeting. It was amazing, of course. I felt like an academic celebrity, having many people – some whom I knew, many whom I did not – express their appreciation for my blog, Conditionally Accepted. Admittedly, with such visibility as an intellectual activist, there is a lingering twinge of the mentality I was forced to adopt in grad school: “what about my research?” I thought privately. Obviously, these colleagues care about my research, as well. But, I found that the meeting, unlike other conferences I’ve attended, was just as much about research as it was about feminism, activism, and building a community. At what other conference would I feel torn between attending a session on feminist public sociology (hosted by the fine folks at Feminist Reflections) and another on campus anti-racist activism? Certainly not the conferences I’ve been attending over the years.

In hindsight, I realize how easy the meeting was emotionally, socially, and professionally. I saw an occasional glance at my nametag, but never followed by averted eyes. I sensed genuine curiosity in meeting others, not the elitist-driven networking to which I’ve grown accustomed at academic conferences. There was even a banquet, featuring a silent auction, a dance party, and delicious food, on the final night of the meeting. Feminist sociologists know how to party after a busy day of talking research and advocacy!

Needless to say, SWS meetings will be one of the regulars on my yearly conference circuit. I am left wondering how different my career and life would be thus far had I attended SWS from the start. Would I have had an easier time finding support for my research and advocacy knowing that I would at least have a network of social justice-minded colleagues in SWS? Would I be in some sort of leadership position within SWS by now? I even saw half a dozen current grad students from my graduate program at the meeting. What do they know that I didn’t?

I can’t speak to paths I did not take, and why others do what they do (or don’t do). I made the decision to focus on becoming involved in mainstream sociology spaces to increase my visibility, widen my professional networks, and enhance my job prospects. SWS did not seem like a feasible opportunity for me because it was not seen as a central in my graduate program. I suffered to a great extent in attempting to navigate the powerful mainstream expectations of my graduate training and my own goals to make a difference in the world. I don’t know that I could have handled being marginal anymore than I already was as a Black queer intellectual activist who studies race, sexualities, and gender.

Find Your Own Feminist Academic Community

What I take from life’s lessons is that one can really benefit from looking just a little bit further to find what one needs. My program devalued research on my communities – Black and LGBTQ. But, had I attended just one SWS conference, I would have found that there exists an academic space where that work is valued without question. My program sought to “beat the activist” out of me; but, in SWS, I would have found regular, open discussions about feminism, activism, and social justice. I know now that if I cannot find support for my goals, my identities, my politics in my immediate context, I am certain I can find support elsewhere. And, if not, there are likely a few others who are willing to join together to build a community that would offer such support. “If you build it, they will come,” or something along those lines. So, no matter how alone we might feel in a specific program, department, university, field, organization, etc., we have to remember that the universe is vast – there is someone or some group out there in which we can find home.

What I take from life’s lessons is that one can really benefit from looking just a little bit further to find what one needs. My program devalued research on my communities – Black and LGBTQ. But, had I attended just one SWS conference, I would have found that there exists an academic space where that work is valued without question. My program sought to “beat the activist” out of me; but, in SWS, I would have found regular, open discussions about feminism, activism, and social justice. I know now that if I cannot find support for my goals, my identities, my politics in my immediate context, I am certain I can find support elsewhere. And, if not, there are likely a few others who are willing to join together to build a community that would offer such support. “If you build it, they will come,” or something along those lines. So, no matter how alone we might feel in a specific program, department, university, field, organization, etc., we have to remember that the universe is vast – there is someone or some group out there in which we can find home.

I don’t want to end by beating myself up, though. I’ve done too much of that in trying to make sense of the traumatic experience of grad school. Rather, I want to end by encouraging those who are in supportive networks to reach out to fellow colleagues and students who you know will benefit from access to such networks. I want to encourage those with power, money, and other resources to share them with someone who may not be able to afford attending a conference that might be transformative for them – but their department won’t support or encourage. I encourage faculty to emphasize to their students how amazing SWS is, or at least having other options besides ASA. Departments and universities can also consider setting aside money and resources to help students attend SWS, the Association of Black Sociologists, Humanist Sociologists, Society for the Study of Social Problems, regional sociology meetings, and those outside of sociology (e.g., National Women’s Studies Association). We do not advance our field by reproducing mainstream and traditional work; we do it by taking risks and thinking outside of the box. We do not benefit from young, aspiring feminist sociologists trudging through their careers thinking that their feminist politics are at odds with success in sociology, nor having them drop out of their programs or leave sociology for more supportive fields. We benefit from supporting the creativity and bravery of the next generation of scholars.

So, I hope to see you at the next SWS meeting. I’ll be the one attendee with the big grin on my face – well, at least one of the many.

___________________

Eric Joy Denise is a Black queer feminist sociologist and intellectual activist, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Richmond. Their research focuses on the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed groups, especially those marginalized by multiple systems of oppression (e.g., LGBTQ people of color). They are the founder and editor of the blog, Conditionally Accepted, which is now hosted by Inside Higher Ed.

Eric Joy Denise is a Black queer feminist sociologist and intellectual activist, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Richmond. Their research focuses on the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed groups, especially those marginalized by multiple systems of oppression (e.g., LGBTQ people of color). They are the founder and editor of the blog, Conditionally Accepted, which is now hosted by Inside Higher Ed.

When I picture traffic in my head, I think of grumpy men driving to jobs they hate, but this is a horrible stereotype of traffic that’s misleading. Women actually make up the vast majority of congestion on the roads. One way of looking at this is to argue that women are causing more congestion on our roads. But another way to talk about this issue (and the way to talk about this issue that is consistent with actual research – and ought to make us feminists smile) is to say that women endure more congestion on the roads.

When I picture traffic in my head, I think of grumpy men driving to jobs they hate, but this is a horrible stereotype of traffic that’s misleading. Women actually make up the vast majority of congestion on the roads. One way of looking at this is to argue that women are causing more congestion on our roads. But another way to talk about this issue (and the way to talk about this issue that is consistent with actual research – and ought to make us feminists smile) is to say that women endure more congestion on the roads. Traffic research has shown that women are more than two times more likely than men to be taking someone else where they need to go when driving (see Nobis and Lenz’s chapter here and Rosenbloom’s research here). Men are more likely to be driving themselves somewhere. Women are also much more likely to string other errands onto the trips in which they are driving themselves somewhere (like stopping at the grocery store on the drive home, going to day care on the way to work, etc.). Traffic experts call this “trip chaining,” but the rest of us call it multi-tasking. What’s more, we also know that women, on average, leave just a bit later than men do for work, and as a result, are much more likely to be making those longer (and more involved) trips right in the middle of peak hours for traffic.

Traffic research has shown that women are more than two times more likely than men to be taking someone else where they need to go when driving (see Nobis and Lenz’s chapter here and Rosenbloom’s research here). Men are more likely to be driving themselves somewhere. Women are also much more likely to string other errands onto the trips in which they are driving themselves somewhere (like stopping at the grocery store on the drive home, going to day care on the way to work, etc.). Traffic experts call this “trip chaining,” but the rest of us call it multi-tasking. What’s more, we also know that women, on average, leave just a bit later than men do for work, and as a result, are much more likely to be making those longer (and more involved) trips right in the middle of peak hours for traffic.

So, back to my first SWS winter meeting. It was amazing, of course. I felt like an academic celebrity, having many people – some whom I knew, many whom I did not – express their appreciation for my blog, Conditionally Accepted. Admittedly, with such visibility as an intellectual activist, there is a lingering twinge of the mentality I was forced to adopt in grad school: “what about my research?” I thought privately. Obviously, these colleagues care about my research, as well. But, I found that the meeting, unlike other conferences I’ve attended, was just as much about research as it was about feminism, activism, and building a community. At what other conference would I feel torn between attending a session on feminist public sociology (hosted by the fine folks at

So, back to my first SWS winter meeting. It was amazing, of course. I felt like an academic celebrity, having many people – some whom I knew, many whom I did not – express their appreciation for my blog, Conditionally Accepted. Admittedly, with such visibility as an intellectual activist, there is a lingering twinge of the mentality I was forced to adopt in grad school: “what about my research?” I thought privately. Obviously, these colleagues care about my research, as well. But, I found that the meeting, unlike other conferences I’ve attended, was just as much about research as it was about feminism, activism, and building a community. At what other conference would I feel torn between attending a session on feminist public sociology (hosted by the fine folks at  What I take from life’s lessons is that one can really benefit from looking just a little bit further to find what one needs. My program devalued research on my communities – Black and LGBTQ. But, had I attended just one SWS conference, I would have found that there exists an academic space where that work is valued without question. My program sought to “

What I take from life’s lessons is that one can really benefit from looking just a little bit further to find what one needs. My program devalued research on my communities – Black and LGBTQ. But, had I attended just one SWS conference, I would have found that there exists an academic space where that work is valued without question. My program sought to “ Eric Joy Denise is a Black queer feminist sociologist and intellectual activist, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Richmond. Their research focuses on the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed groups, especially those marginalized by multiple systems of oppression (e.g., LGBTQ people of color). They are the founder and editor of the blog,

Eric Joy Denise is a Black queer feminist sociologist and intellectual activist, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Richmond. Their research focuses on the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed groups, especially those marginalized by multiple systems of oppression (e.g., LGBTQ people of color). They are the founder and editor of the blog,

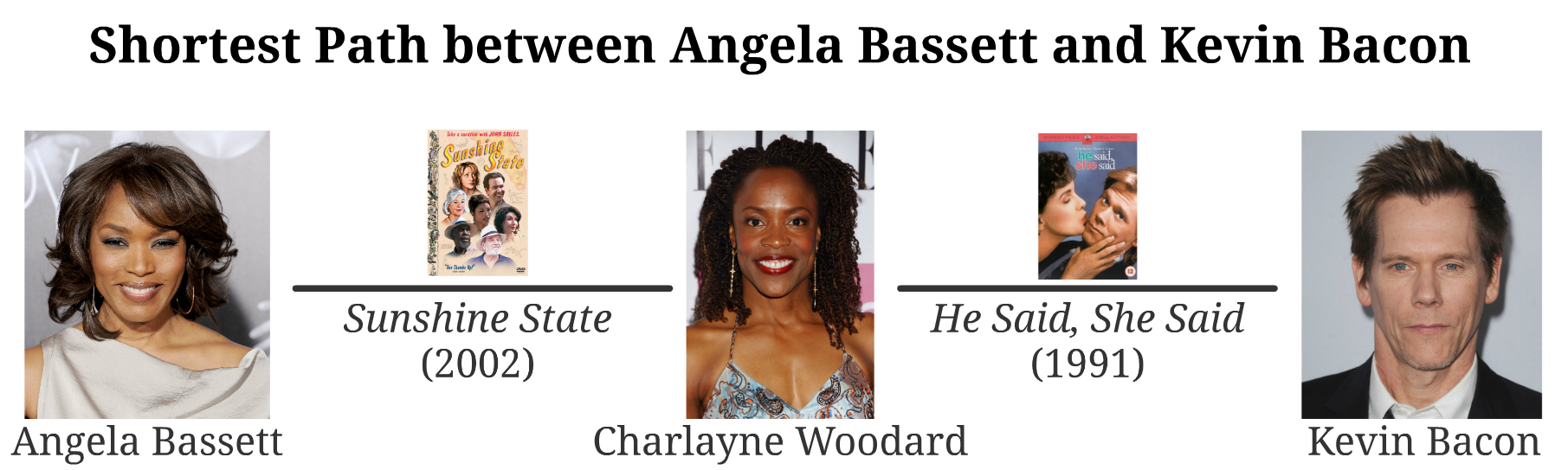

The 2016 Oscar nominations were just announced. This is the second year in a row that all 20 acting nominees are white–prompting the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite.

The 2016 Oscar nominations were just announced. This is the second year in a row that all 20 acting nominees are white–prompting the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite.

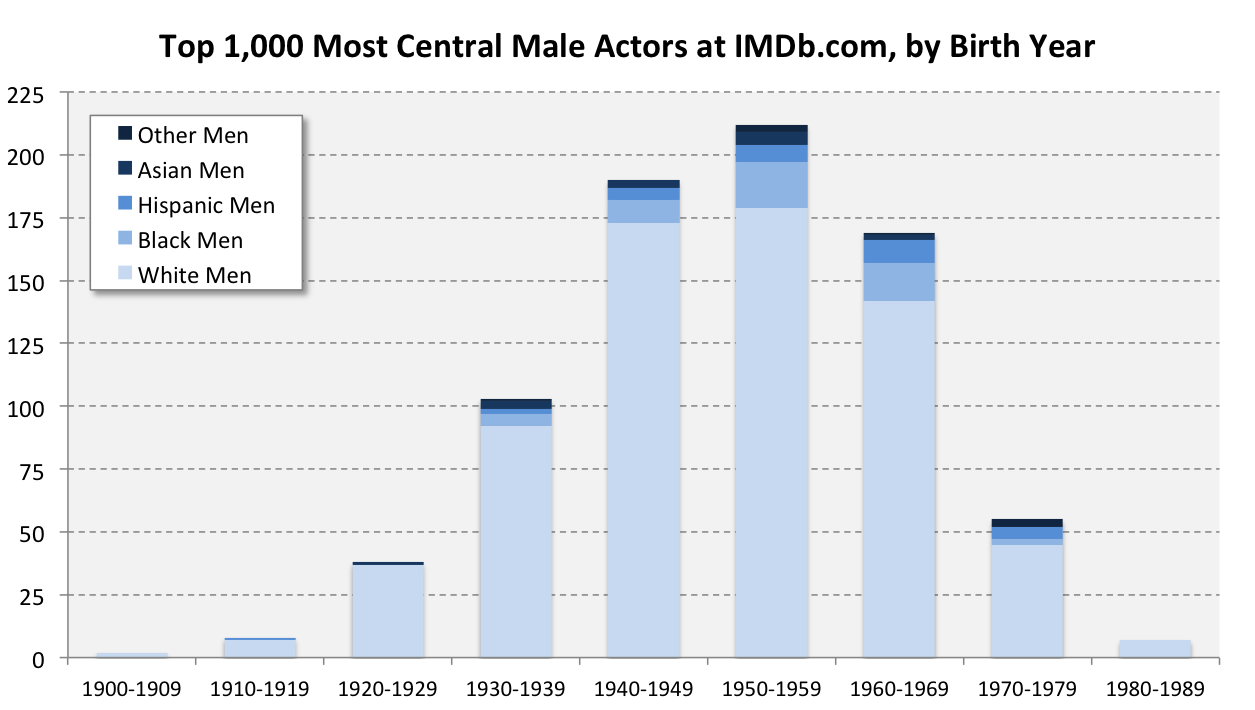

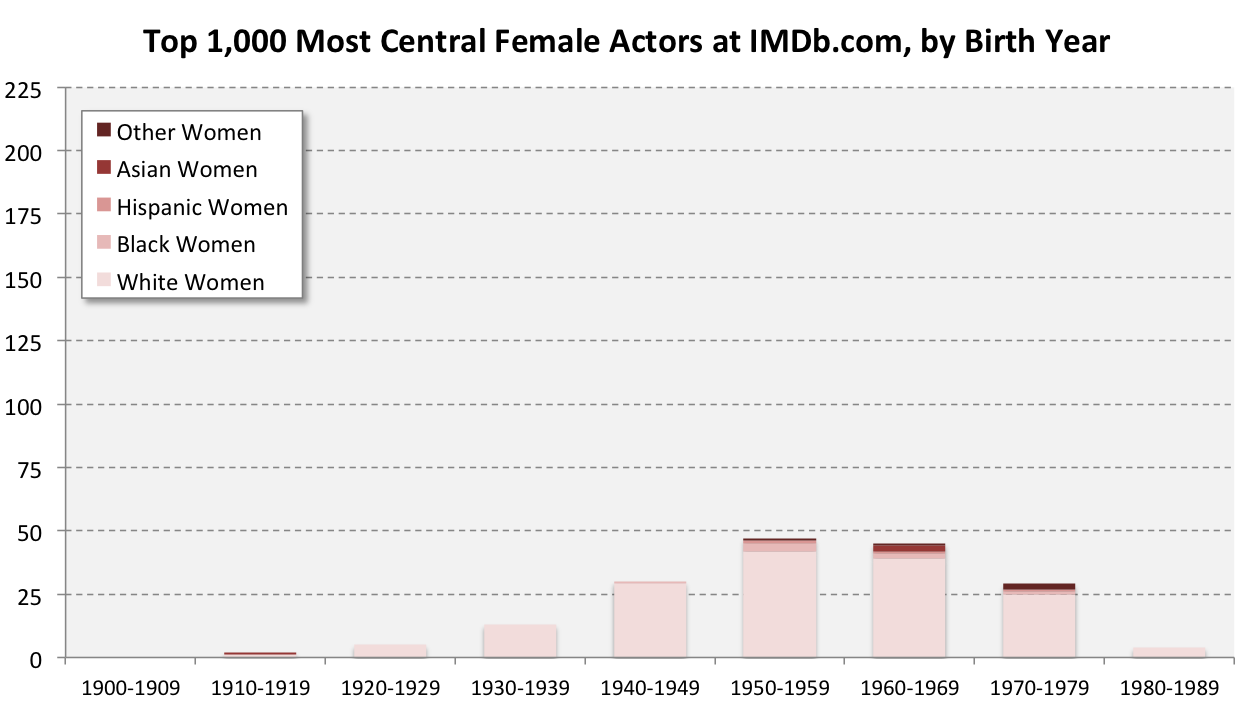

It’s a powerful way of saying that Hollywood continues to be a (white) boy’s club. But they’re also an old white boy’s club as well. I also collected data on birth year. And while the 50’s were the best decade to be born in if you want to be among the 1,000 most “central” actors today, the data for the men skews a bit older.** This lends support to the claim that men do not struggle to find roles as much as women do as they age–which may also support the claim that there are more complex roles available to men (as a group) than women.

It’s a powerful way of saying that Hollywood continues to be a (white) boy’s club. But they’re also an old white boy’s club as well. I also collected data on birth year. And while the 50’s were the best decade to be born in if you want to be among the 1,000 most “central” actors today, the data for the men skews a bit older.** This lends support to the claim that men do not struggle to find roles as much as women do as they age–which may also support the claim that there are more complex roles available to men (as a group) than women.

The other things I noticed quickly were that: (1) Hispanic and Asian men among the top 1,000 actors list are extremely likely to be typecast as racial stereotypes, and (2) there are more multiracial women among the top 1,000 actors than either Hispanic or Asian women.

The other things I noticed quickly were that: (1) Hispanic and Asian men among the top 1,000 actors list are extremely likely to be typecast as racial stereotypes, and (2) there are more multiracial women among the top 1,000 actors than either Hispanic or Asian women.