Leonard Nimoy attended University of California, Los Angeles in 1971 to study photography. He had already filmed the original Star Trek television series, which didn’t develop a cult following until reruns of the show aired in the 1970s. His love of photography, however, predates his portrayal of the half-Vulcan, Spock.

While this role is what most people are sure to remember Nimoy by, I will always think of him as a skilled photographer who engaged cultural rhetoric on the gendered and sexual body. Perhaps his most controversial work is titled Shekhina, which is his attempt to capture divinity in a “feminine” form. Shekhina, he explains here, is a Jewish “deity”—one so luminous that men in synagogue have to look down, away, or otherwise shield their faces. As a child, he wondered, “Why hide the face? Why can’t we look?”

Spending seven years searching for Shekhina through his photography, Nimoy produced images he describes here as a “crossover between sensuality and religion.” Consequently, he was asked to not show his photographs at a Seattle synagogue where he had been scheduled to talk about his work. The controversy around this censorship arose because of a religious discomfort with sexual portrayals of women—as sexually desirable and perhaps as sexually desiring—and the association of women with power. Nimoy saw his work as a “very strong feminist statement” partly because “to some degree, in the orthodox community, that makes people uncomfortable—the idea that god is a woman.”

Nimoy’s Shekhina series at times conflates femininity with desirability, but it also challenges us to think of women as corporeally and inherently powerful. He captures the simultaneous idolization of femininity and invisibility of the female body in religion, specifically in Judaism. And the looking away from Shekhina speaks to her ideological incandescence as well as to the way religion is structured around gender dichotomies, whereby women are cast within an androcentric institution as heterosexually alluring and men as driven by primitive roots—or by what Martha McCaughey refers to in her book, The Caveman Mystique, as Darwinian ideas about sex.

At the same time Nimoy challenges the invisibility of a powerful, deific femininity, he also privileges hegemonic corporeal norms, situating in his frames thin, white women with long hair who often peer down. [When they look directly at the viewer, the images take to task representations of women as meek]. Nimoy recognized this, noting that it was not until he began work on The Full Body Project that he realized very specific bodies and definitions of beauty dominated his work. A large-bodied model contacted him to see if he was interested in photographing her precisely because she represented a different sort of body than he was used to shooting.

Joan Jacob Brumberg’s book on The Body Project looks historically to demonstrate the ways social norms have turned women’s bodies into all consuming projects. At any given time, women’s bodies are defined as malleable and docile, evoking Michel Foucault’s notion of the panopticon, by which women internalize narrow, sexist bodily expectations. To take on work that captures an alternative image of beauty, Nimoy said he had to ask himself, “Will you do something that scares you?” In other words, could he do justice to a woman who challenged him to rethink how he was portraying beautiful bodies and women’s sexuality?

Nimoy’s relationship with the model evolved into a larger venture as he found that when he showed his photography, it was pictures of this full-bodied woman that “got the attention. So I thought, there’s something going on there in our culture about this kind of body.” Nimoy appeared to know he was engaging larger conversations about the misogyny of fat-shaming and problematic definitions of what counts as a beautiful and thus culturally valued woman. He found a San Francisco burlesque group called The Fat-Bottom Revue that was happy to pose for him; the women were comfortable in their own skin and used the art of dance and theater to do body-positive activism. Along with these women, Nimoy highlighted bodies as cultural symbols that are constrained by gendered structures but also vehicles of agency through which we experience the world around us and develop intellectual, emotional, and physical relationships with others. [For more on The Full Body Project, see here and here].

As a gender scholar who studies issues of masculinity, I can’t help but wonder where the masculine body is in Nimoy’s work. Why not capture sensual photos of large bodied men? Or of female masculinity? Focusing on femininity and female bodies relegates “beauty” to feminine identified bodies, but it also keeps women at the center of a discussion of bodies and structures of power. [In my own research, I explore men’s relationship to beauty and the beauty industry. See here]. What Nimoy does so well in his photography is acquaint us with images of bodies that beget conversations about gender, sexuality, and social hierarchies. As Nimoy noted, his photos put us in touch “with something beyond what you see in the image;” and he saw his work as not about any particular model or group of models, but rather about “feminine power.”

_____________________

Kristen Barber is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and a Faculty Affiliate in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. She teaches courses on gender, inequality, work, and qualitative methods and is on the Gender & Society Editorial Board. Her book on women working in the men’s grooming industry is forthcoming with Rutgers University Press.

Kristen Barber is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and a Faculty Affiliate in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. She teaches courses on gender, inequality, work, and qualitative methods and is on the Gender & Society Editorial Board. Her book on women working in the men’s grooming industry is forthcoming with Rutgers University Press.

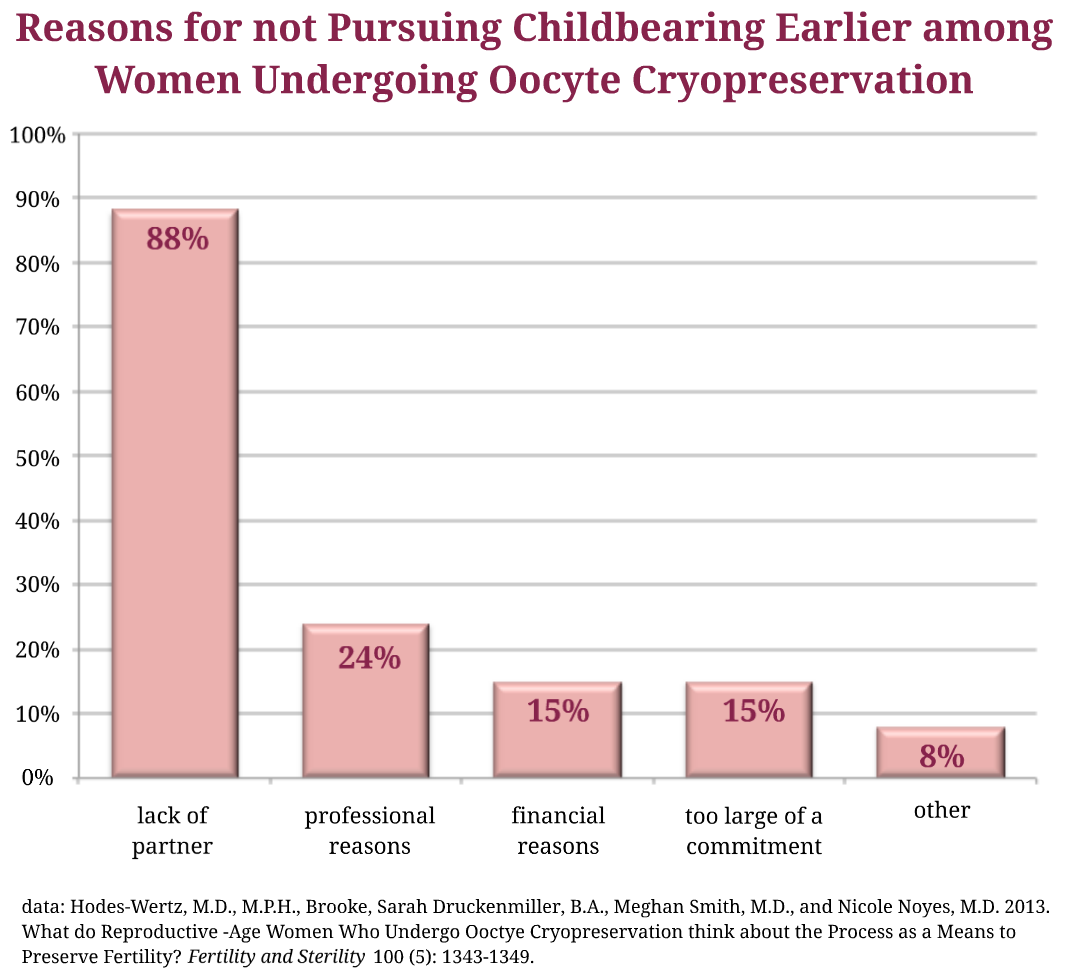

While they were allowed to select all of the possible reasons that might apply, only about a quarter of the sample cited “professional reasons” for not having children earlier. The overwhelming majority of women (88%) claimed that “lack of partner” was the primary reason (see our adapted graph).2

While they were allowed to select all of the possible reasons that might apply, only about a quarter of the sample cited “professional reasons” for not having children earlier. The overwhelming majority of women (88%) claimed that “lack of partner” was the primary reason (see our adapted graph).2 Indeed, as

Indeed, as  There is something that is bothering me about the phrases, “A real man doesn’t hit a woman,” or “No one should ever hit a woman.” This seems to be the go-to phrase in response to the video of Ray Rice punching and knocking out his wife. A friend with tickets to an NFL game wanted to wear a t-shirt that represented her commitment to girls’ and women’s rights. One person suggested, “Don’t Hit Girls.” On the surface, who could argue with that?

There is something that is bothering me about the phrases, “A real man doesn’t hit a woman,” or “No one should ever hit a woman.” This seems to be the go-to phrase in response to the video of Ray Rice punching and knocking out his wife. A friend with tickets to an NFL game wanted to wear a t-shirt that represented her commitment to girls’ and women’s rights. One person suggested, “Don’t Hit Girls.” On the surface, who could argue with that? Mimi Schippers

Mimi Schippers

Michelle Janning, Senior Scholar with the

Michelle Janning, Senior Scholar with the

In The Incredibles, Bob Parr’s incredible strength and monstrous body look silly accomplishing domestic tasks or even occupying a traditionally domestic masculinity. His small car helps is body appear laughable in this role as he drives to work. At work, Bob’s desk plays a similar role. His body is depicted as not belonging there—domesticity is symbolically holding him back. This sort of “crisis of masculinity” narrative plays out in the stories of many of these characters. So, when they occupy the role they are initially depicted as denying, the narrative creates a frame for the audience to collectively experience relief as they take on the heroic roles for which their bodies symbolically situate them as more naturally suited. The scene in The Incredibles in which Bob Parr (Mr. Incredible) quits his job by punching his boss (whose physically inferior body is regularly situated alongside Bob’s for comic relief) through a wall is perhaps the most exaggerated example of this. The pleasures these films invite us to share at these moments when gendered hierarchies of embodiment are symbolically put on display play a role in reproducing inequality.

In The Incredibles, Bob Parr’s incredible strength and monstrous body look silly accomplishing domestic tasks or even occupying a traditionally domestic masculinity. His small car helps is body appear laughable in this role as he drives to work. At work, Bob’s desk plays a similar role. His body is depicted as not belonging there—domesticity is symbolically holding him back. This sort of “crisis of masculinity” narrative plays out in the stories of many of these characters. So, when they occupy the role they are initially depicted as denying, the narrative creates a frame for the audience to collectively experience relief as they take on the heroic roles for which their bodies symbolically situate them as more naturally suited. The scene in The Incredibles in which Bob Parr (Mr. Incredible) quits his job by punching his boss (whose physically inferior body is regularly situated alongside Bob’s for comic relief) through a wall is perhaps the most exaggerated example of this. The pleasures these films invite us to share at these moments when gendered hierarchies of embodiment are symbolically put on display play a role in reproducing inequality. Indeed, side-kicks and villains are most often depicted as occupying masculine bodies less worthy of status. These masculine counter-types (like Randall in Monsters Inc., Sid Phillips in Toy Story, or Buddy Pine/Syndrome in The Incredibles) embody masculinities portrayed as “deserving” the “justice” they are served.

Indeed, side-kicks and villains are most often depicted as occupying masculine bodies less worthy of status. These masculine counter-types (like Randall in Monsters Inc., Sid Phillips in Toy Story, or Buddy Pine/Syndrome in The Incredibles) embody masculinities portrayed as “deserving” the “justice” they are served.