This is the second half of a two-post series on the pro-feminist and activist Chris Norton at Feminist Reflections by Michael A. Messner. The first half of “Learning from Chris Norton over three decades—Part I” can be found HERE.

…

Flash forward to 2010. I was now a tenured full professor, pushing 60, a number of books under my belt. I was working with two young male Ph.D. students who in some ways reminded me of myself thirty years earlier—inspired by feminism, wanting to have an impact on the world. Both Tal Peretz and Max Greenberg had, as undergrads, gotten involved in campus-based violence prevention work with men. Unlike three decades ago, this work had become pretty much institutionalized; a guy like Tal or Max now can plug in to a campus or community organization, be handed an anti-violence curriculum, and get to work with boys and men. I figured this was a great opportunity to do a study with these two guys, tapping in to the roots of men’s work against gender-based violence in the 70s and 80s, and contrasting it with the work being done today.

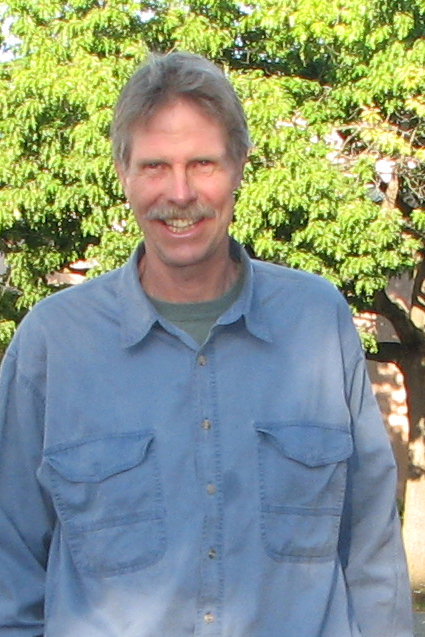

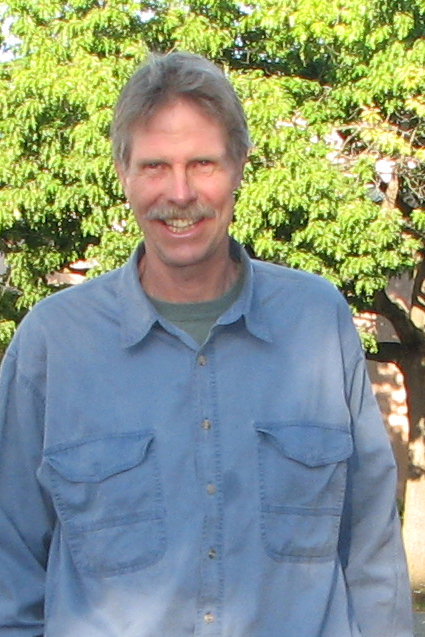

Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before.

Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before.

We went out to lunch, and did what older guys do: caught up on each others’ lives, shared our hopes, fears, and challenges we’d faced with our kids, commiserated about our ageing bodies. On this latter topic, Chris had more serious news to share than I. He was facing, with strength and optimism, a liver transplant in the near future.

We returned to his home, and settled in for the interview in a cozy cabin-like structure behind his and Mary’s home. We fell right in to a nice conversation, and I used bits of the transcript of my 1980 interview with Chris to prod his memory, and to probe ways in which he’d changed, or not, since then. Most interesting to me were his reflections on the work that MASV had done so many years ago. He joined the several other MASV men whom I would eventually also interview in saying that he was very proud of the work the group had done. But in retrospect, he said he wondered how effective they’d been, and figured that if the group had it to do all over again, they might have done their work differently:

I don’t think I would go at it at all the way we did then, ‘cause I think in some ways, … I think we were doing something to prove something to ourselves and other people of our age group, and I don’t think we were thinking about, like, what’s it like to be a teenage boy in high school, and what are these images going to do to you when they’re shown up on a screen, and is it going to have any of the effect that we’re hoping to have? And I think it would have been really good to kind of get guys to talk about, well, there’s issues of bullying, issues of, you know, being popular, not popular. I mean, it seems like there could be a lot of things that could have been much more valuable, ‘cause in some ways, I think we almost had this stick and we’re going to beat you over the head with this thing. And… perhaps if they felt like they were more understood, maybe they could be more understanding of women and, and where women are coming from. And I think that would be more the way I would go about it now.

[Back then], we were really just making it up, I mean, it was the seat of our pants… we felt like we should be doing something. We were feeling like we need to be also talking about the same things that the women were talking about—but we basically just took their analysis and presented it. You know, it didn’t—it didn’t feel like it was coming from our core, you know, from who we were, other than maybe from our guilt

And, and you know, I think—having more of a positive vision of what a man should be, rather than going in there and telling men what they shouldn’t be doing—having a more pro-active, having a more kind of like, basically creating an ethic of, “This is what a man should do.” You know, this is, this is a positive thing for a man to do, and also like, what does a man want? You know, rather than like, “Oh, you shouldn’t be bad,” but…you wanna have a good relationship, you wanna have a relationship with someone that’s based on some degree of equality, on some degree of, of mutual respect, of everyone having opportunities, or people feeling good about their lives, about who they are. And, that presupposes having some degree of, of understanding of who you are yourself and what you want. And I felt like we weren’t, back then, we weren’t coming at it from that—it was more sort of like, you know, men are bad—Andrea Dworkin told us this—we know men are bad, we are bad, we’re gonna’ go and tell the high school boys that they’re bad too, for looking at pornography, and that pornography’s gonna’ make them badder than they already are. And, there wasn’t that—I think there’s gotta’ be a positive vision. And you have to have, I mean, you don’t want to be blind to the bad stuff that goes on, but there has to be kind of some upside for doing this, ‘cause I don’t think otherwise people are gonna’ really pay any attention or wanna listen to you.

Chris’s statement very neatly encapsulated about thirty years of change in the ways that men now approach doing violence prevention work with boys and men. In Some Men, the book that Max Greenberg, Tal Peretz and I wrote from this research, we chronicle the grassroots of this activism—set in place in the 70s and 80s by community groups like MASV—in part because it is important to honor the foundations of positive social change. But it’s also important because today’s younger activists, however savvy and pragmatic they may be about the ways they approach boys and men with their message, may also have lost something very important that earlier activists like Chris Norton had: a grounding in a larger view of social change that viewed their efforts to stop sexist violence against women as intricately connected with efforts to humanize and bring justice to the world. For groups like MASV, feminist work with boys and men, Chris explained, was an integral part of a larger transformative movement:

… an important way of sort of humanizing socialism, or getting rid of some of the hard-edged more Stalinistic tendencies that some socialist movements could have. And it also just made a lot of sense [for] those of us too, who also were rejecting militarism and the traditional terms of being masculine or man, and were looking for some kind of a new way—when I came to Berkeley initially I was involved in the anti-war movement, and lived in communal houses, and we’d gotten involved in the food conspiracy, and—it was all part of this whole, you know, sort of community, alternative society in a way that we kinda’ felt like we were creating it back then.

In retrospect, like many radicals of his generation, Chris expressed frustration with the current prospects for transformative social change.

I think I’ve retreated some degree from utopianism. But I do feel that it’s definitely possible to have a far more egalitarian society than we do. And I just, I feel like—and that’s part of my frustration too, is those of us who feel that way haven’t found ways to be very effective in putting forward that vision and, and making that vision something that’s attractive to people, and making people realize that what we’re living under is not actually that great for a lot of people, and it’s very difficult for a lot of people.

Part of my goal in writing Some Men with Max and Tal was to encourage today’s anti-violence activists to re-connect to that larger vision. It is stories from this generation of activists like Chris Norton that help to keep alive this larger vision.

The community bonds that sustain that vision were palpable when I attended Chris Norton’s memorial service in 2012, after he had succumbed to cancer. Included among the scores of family and friends celebrating Norton’s life were a handful of MASV men—guys who in their youth had pioneered anti-violence work. Now considerably older, they shared a sense of pride in what they had accomplished so many years ago. Following MASV’s demise, they had gone on to do other progressive work: Chris Anderegg worked for years helping women’s DV shelters with their finances; Larry Mandella created workshops for fathers; Santiago Casal did community organizing to get a memorial built in Berkeley for civil rights leader Cesar Chavez. All of them, in their own ways, were clearly in it for the long haul.

Still today, I am not and probably never will be much of an activist. But I hope that my research and writing makes some small contribution to progressive thinking, and progressive social change, a contribution that both honors and learns from the brave and important work that’s been done in the past by the doers of the world, like Chris Norton, whom I so admire, and whose collective work helps to make the world a better and more just place.

_____________________________

Michael A. Messner is professor of sociology and gender studies at the University of Southern California, and author (with Max Greenberg and Tal Peretz) of Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Michael A. Messner is professor of sociology and gender studies at the University of Southern California, and author (with Max Greenberg and Tal Peretz) of Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women (Oxford University Press, 2015).

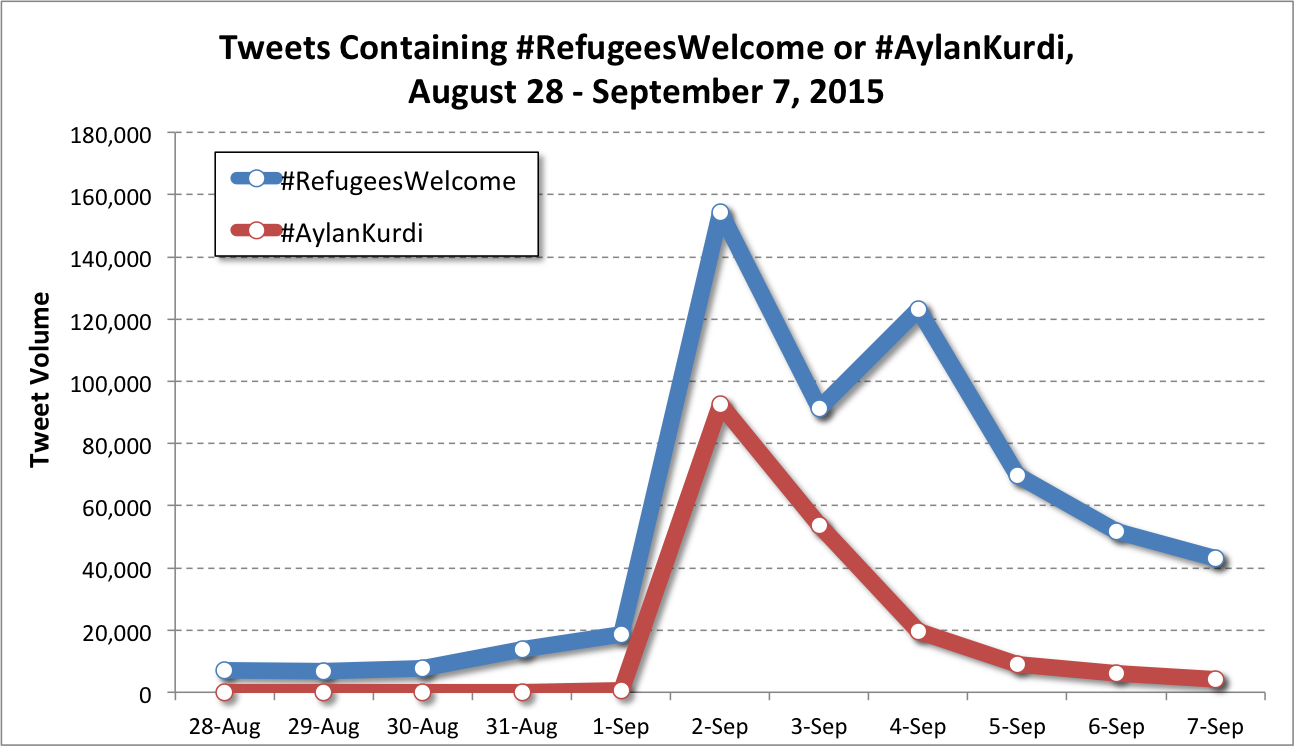

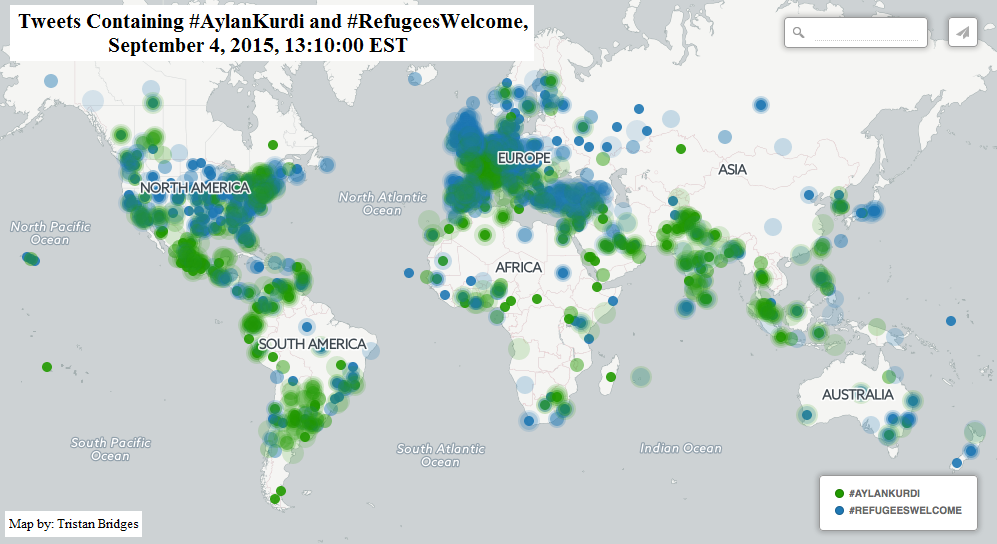

When we georeference and map tweets containing the hashtags #RefugeesWelcome and #AylanKurdi, we can also see how this unfolded around the world. Twitter is a crude measure of impact. Yet, just as Barnard and Shoumali suggested, a single tragedy amidst a conflict that has led to the deaths of so many seems to have helped to capture the attention of the world. See the snapshot of Twitter activity around the world using the hashtags #AylanKurdi (green) and #RefugeesWelcome (blue) two days after the photograph went viral (below).

When we georeference and map tweets containing the hashtags #RefugeesWelcome and #AylanKurdi, we can also see how this unfolded around the world. Twitter is a crude measure of impact. Yet, just as Barnard and Shoumali suggested, a single tragedy amidst a conflict that has led to the deaths of so many seems to have helped to capture the attention of the world. See the snapshot of Twitter activity around the world using the hashtags #AylanKurdi (green) and #RefugeesWelcome (blue) two days after the photograph went viral (below). So, can an image of a child change the world? Typically, no. But, a powerful image under the right conditions might have an impact no one could have predicted.

So, can an image of a child change the world? Typically, no. But, a powerful image under the right conditions might have an impact no one could have predicted.

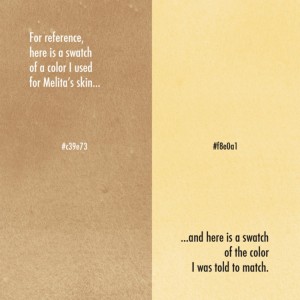

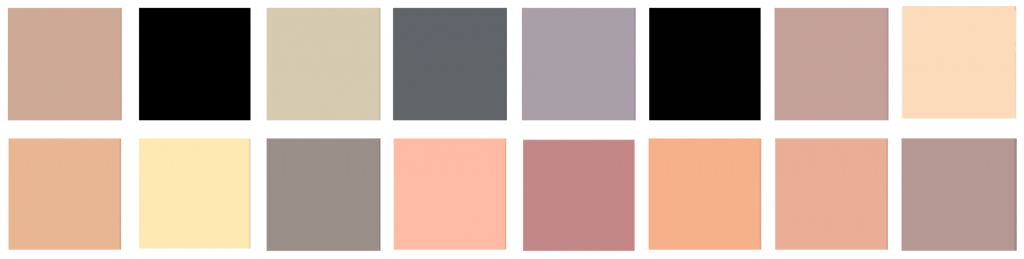

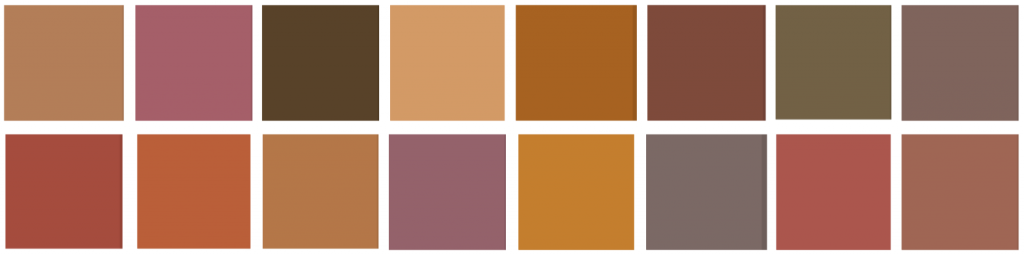

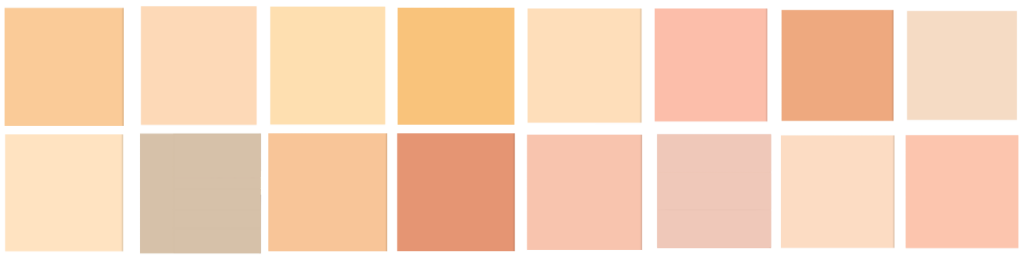

In the panel of the cartoon reproduced here, you can see Wimberly’s original color swatch for the character alongside the swatch he was instructed to use for the character.

In the panel of the cartoon reproduced here, you can see Wimberly’s original color swatch for the character alongside the swatch he was instructed to use for the character.

Now, perhaps it was unfair to use Batman as a comparison as his character is more often depicted at night than is Wonder Woman—a fact which might mean he is more often depicted in dynamic lighting than she is. But it’s an interesting thought experiment. Based on this sample, two things that seem immediately apparent. Amazing-man is depicted much darker when his character is drawn angry. And Wonder Woman exhibits the least color variation of the three. Whether this is representative is beyond the scope of the post. But, it’s an interesting question. While

Now, perhaps it was unfair to use Batman as a comparison as his character is more often depicted at night than is Wonder Woman—a fact which might mean he is more often depicted in dynamic lighting than she is. But it’s an interesting thought experiment. Based on this sample, two things that seem immediately apparent. Amazing-man is depicted much darker when his character is drawn angry. And Wonder Woman exhibits the least color variation of the three. Whether this is representative is beyond the scope of the post. But, it’s an interesting question. While  Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before.

Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before. Michael A. Messner

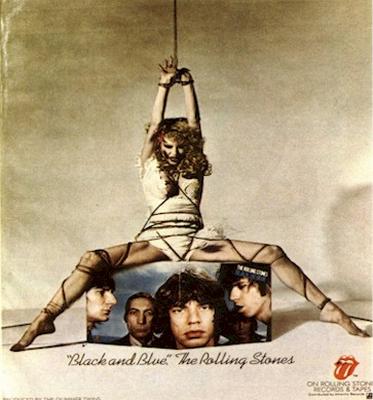

Michael A. Messner Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.

Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.

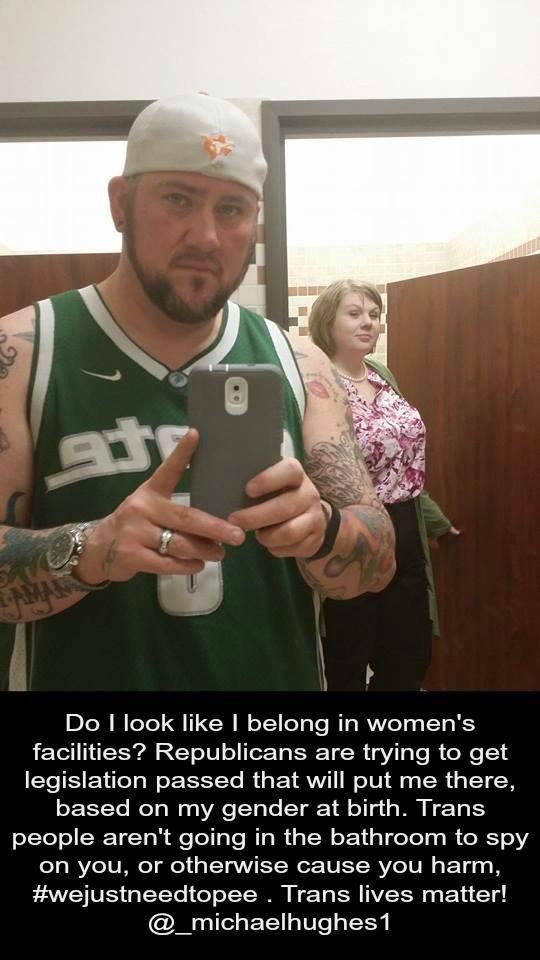

Those introducing bathroom bills most often justify them as being about “protection,” “public safety,” and as attempts to reduce violence and assault. The bills rely on the transphobic myth that transgender individuals are sexually perverse and that they are likely to be sexual predators. Thus, defenders of these bills often claim that they are about protecting cis-gender people. This avoids the troubling truth that transgender individuals are far more likely to have violence committed against them than they are to commit this kind of violence against others. Indeed,

Those introducing bathroom bills most often justify them as being about “protection,” “public safety,” and as attempts to reduce violence and assault. The bills rely on the transphobic myth that transgender individuals are sexually perverse and that they are likely to be sexual predators. Thus, defenders of these bills often claim that they are about protecting cis-gender people. This avoids the troubling truth that transgender individuals are far more likely to have violence committed against them than they are to commit this kind of violence against others. Indeed,