Originally posted at Democratic Socialists of America

In the 1950s, a collection of sociologists and psychologists (which included, among others, Theodor Adorno) wrote The Authoritarian Personality. They were attempting to theorize the type of personality — a particular psychology — that gave rise to fascism in the 1930s. Among other things, they suggested that the “authoritarian personality” was characterized by a normative belief in absolute obedience to their authority in addition to the practical enactment of that belief through direct and indirect marginalization and suppression of “subordinates.” While Adorno and his colleagues did not consider the gender of this personality, today gender scholars recognize authoritarianism as a particular form of masculinity, and current U.S. president Donald Trump might appear to be a prime illustration of a rigid and inflexible “authoritarian personality.”

Yet Trump’s masculinity avoids a direct comparison to this label precisely because of the fluidity he projects. Indeed, the “authoritarian personality” is overly fixed, immutable, and one dimensional as a psychoanalytical personality type. Sociologists understand identities as more flexible than this. Certain practices of Trump exemplify the fluctuations of masculinity that illustrate this distinction, and the transformations in his masculinity are highly contingent upon context. While this is a common political strategy, Trump’s shifts are important as they enable him to construct a “dominating masculinity” that perpetuates diverse forms of social inequality. Dominating masculinities are those that involve commanding and controlling interactions to exercise power and control over people and events. These masculinities are most problematic when they also are hegemonic and work to legitimize unequal relations between women and men. Here are a few examples:

First, in his speeches and public statements prior to being elected, Trump bullied and subordinated “other” men by referring to them as “weak,” “low energy,” or as “losers,” or implying they are “inept” or a “wimp.” (“Othering” is a social process whereby certain people are viewed and/or treated as somehow fundamentally different and unequal.) For example, during several Republican presidential debates, Trump consistently labeled Marco Rubio as “little Marco,” described Jeb Bush as “low energy Jeb,” implied that John McCain was a “wimp” because he was captured and tortured during the Vietnam War, and suggested that contemporary military veterans battling PTSD are “inept” because they “can’t handle” the “horror” they observed in combat. In contrast, Trump consistently referred to himself as, for example, strong, a fighter, and as the embodiment of success. In each case, Trump ascribes culturally-defined “inferior” subordinate gender qualities to his opponents while imbuing himself with culturally defined “superior” masculine qualities. This pairing signifies an unequal relationship between masculinities—one both dominating and hegemonic (Trump) and one subordinate (the “other” men).

A second example of Trump’s fluid masculinity applies to the way he has depicted himself as the heroic masculine protector of all Americans. This compassion may appear, at first blush, at odds with the hegemonic masculinity just discussed. For example, in his Republican Convention speech Trump argued that he alone can lead the country back to safety by protecting the American people through the deportation of “dangerous” and “illegal” Mexican and Muslim immigrants and by “sealing the border.” In so doing, Trump implied that Americans are unable to defend themselves — a fact he used to justify his need to “join the political arena.” Trump stated: “I will liberate our citizens from crime and terrorism and lawlessness” by “restoring law and order” throughout the country — “I will fight for you, I will win for you.” Here Trump adopts a position as white masculine protector of Americans against men of color, instructing all US citizens to entrust their lives to him; in return, he offers safety. Trump depicts himself as aggressive, invulnerable, and able to protect while all remaining US citizens are depicted as dependent and uniquely vulnerable. Trump situates himself as analogous to the patriarchal masculine protector toward his wife and other members of the patriarchal household. But simultaneously, Trump presents himself as a compassionate, caring, and kind-hearted benevolent protector, and thereby constructs a hybrid hegemonic masculinity consisting of both masculine and feminine qualities.

Third, in the 2005 interaction between Trump and Billy Bush on the now infamous Access Hollywood tour bus, Trump presumes he is entitled to the bodies of women and (not surprisingly) admits committing sexual assault against women because, according to him, he has the right. He depicts women as collections of body parts and disregards their desires, needs, expressed preferences, and their consent. After the video was aired more women have come forward and accused Trump of sexual harassment and assault. Missed in discussions of this interaction is how that dialogue actually contradicts, and thus reveals, the myth of Trump’s protector hegemonic masculinity. The interaction on the bus demonstrates that Trump is not a “protector” at all; he is a “predator.”

Trump’s many masculinities represent a collection of contradictions. Trump’s heroic protector hegemonic masculinity should have been effectively unmasked, revealing a toxic predatory heteromasculinity. Discussions of this controversy, however, failed to articulate any sign of injury to his campaign because Trump was able to connect with a dominant discourse of masculinity often relied upon to explain all manner of men’s (mis)behavior — it was “locker room talk,” we were told. And the sad fact is, the news cycle moved on.

We argue that Trump has managed such contradictions by mobilizing, in certain contexts, what has elsewhere (and above) been identified as a “dominating masculinity” (see here, here and here) — involving commanding and controlling specific interactions and exercising power and control over people and events. This dominating masculinity has thus far centered on six critical features:

- Trump operates in ways that cultivate domination over others he works with, in particular rewarding people based on their loyalty to him.

- Trump’s dominating masculinity serves the interests of corporations by cutting regulations, lowering corporate taxes, increasing military spending, and engaging in other neoliberal practices, such as attempting to strip away healthcare from 24 million people, defunding public schools, and making massive cuts to social programs that serve poor and working-class people, people of color, and the elderly.

- Trump has relied on his dominating masculinity to serve his particular needs as president, such as refusing to release his tax returns and ruling through a functioning kleptocracy (using the office to serve his family’s economic interests).

- This masculinity is exemplified through the formulation of a dominating militaristic foreign policy (for example, U.S. airstrikes of civilians in Yemen, Iraq and Syria have increased dramatically under Trump; the MOAB bombing of Afghanistan; threats to North Korea) rather than engaging in serious forms of diplomacy. Trump has formed a global ultraconservative “axis of evil”— whose defining characteristics are kleptocracy and dominating masculinity — with the likes of Putin (Russia), el-Sisi (Egypt), Erdogan (Turkey), Salman (Saudi Arabia), Duterte (Philippines) among others.

- So too has this dominating masculinity had additional effects “at home” as Trump prioritizes domestically the repressive arm of the state through white supremacist policies such as rounding-up and deporting immigrants and refugees as well as his anti-Muslim rhetoric and attempted Muslim ban.

- Trump’s dominating masculinity attempts to control public discourse through his constant tweets that are aimed at discrediting and subordinating those who disagree with his policies.

Trump’s masculinity is fluid, contradictory, situational, and it demonstrates the diverse and crisscrossing pillars of support that uphold inequalities worldwide. From different types of hegemonic masculinities, to a toxic predatory heteromasculinity, to his dominating masculinity, Trump’s chameleonic display is part of the contemporary landscape of gender, class, race, age and sexuality relations and inequalities. Trump does not construct a consistent form of masculinity. Rather, he oscillates — at least from the evidence we have available to us. And in each case, his oscillations attempt to overcome the specter of femininity — the fear of being the unmasculine man — through the construction of particularized masculinities.

It is through these varying practices that Trump’s masculinity is effective in bolstering specific forms and systems of inequality that have been targeted and publicly challenged in recent history. Durable forms of social inequality achieve resilience by becoming flexible. By virtue of their fluidity of expression and structure, they work to establish new pillars of ideological support, upholding social inequalities as “others” are challenged. As C. J. Pascoe has argued, a dominating masculinity is not unique to Trump or only his supporters; Trump’s opponents rely on it as well (see also sociologist Kristen Barber’s analysis of anti-Trump masculinity tactics). And it is for these reasons that recognizing Trump’s fluidity of masculinity is more than mere academic observation; it is among the chief mechanisms through which contemporary forms of inequality — from the local to the global — are justified and persist today.

The journal,

The journal,

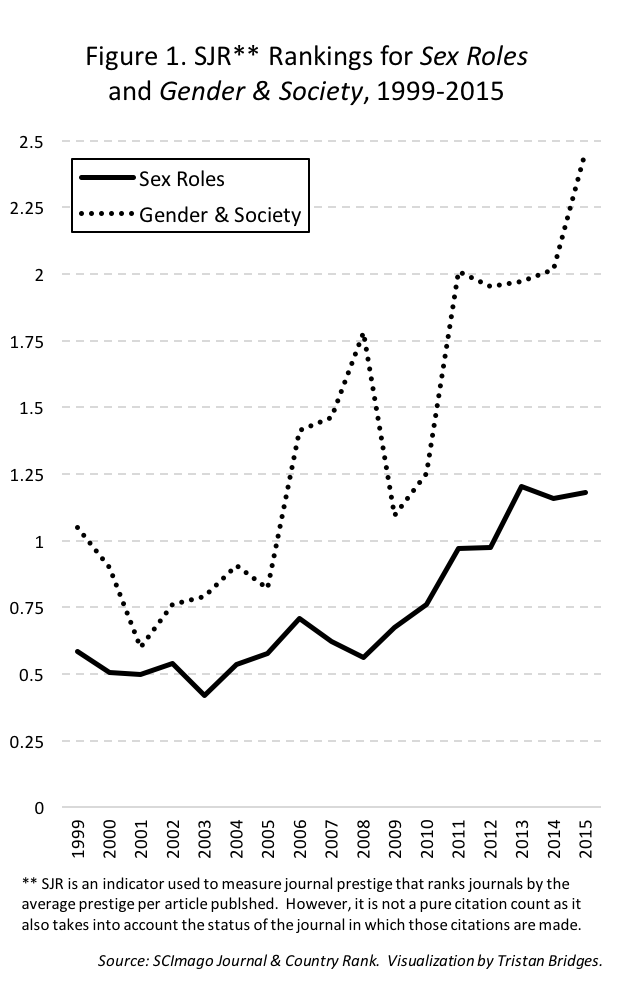

Acker’s short 6-page article was published in the same journal that had published Raewyn Connell’s article,

Acker’s short 6-page article was published in the same journal that had published Raewyn Connell’s article,

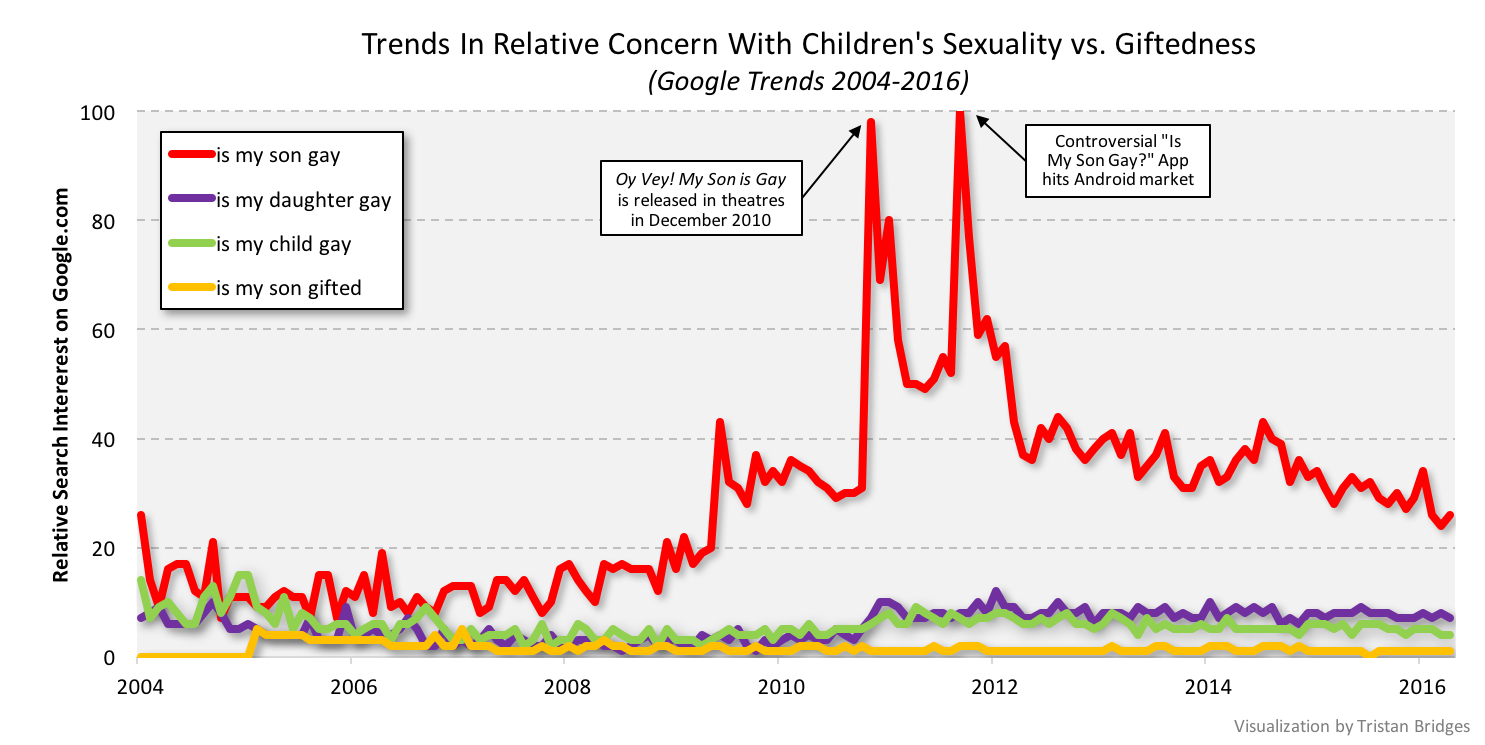

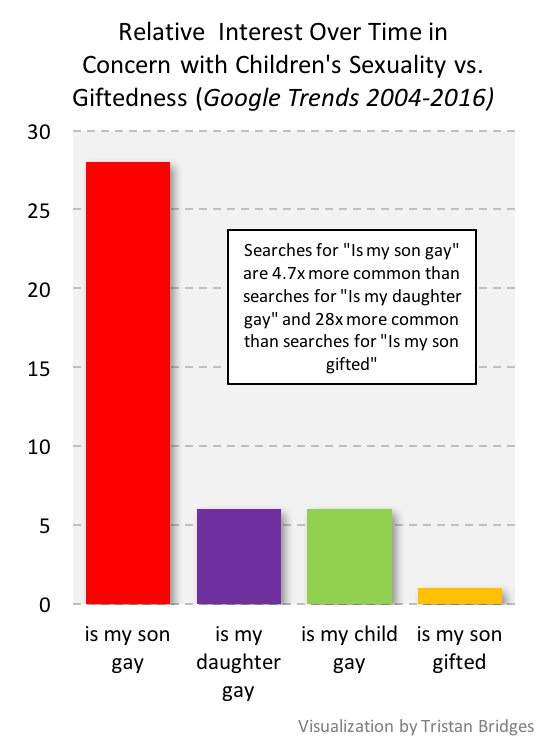

Indeed, over the period of time illustrated here, people were 28x more likely to search for “is my son gay” than they were for “is my son gifted.” And searches for “is my son gay” were 4.7x more common than searches for “is my daughter gay.”

Indeed, over the period of time illustrated here, people were 28x more likely to search for “is my son gay” than they were for “is my son gifted.” And searches for “is my son gay” were 4.7x more common than searches for “is my daughter gay.” As the week advanced, and fathers’ day draws closer, I have already noticed the reordering of the news, a staged dismissal so common in media outlets. Those queer and Brown must continue to raise this as an issue, to not let the comfort of your organized, White hetero-lives go back to normal. You never left that comfort, you just thought about “those” killed. But it was “Latino night” at a gay club. I do not have that luxury. I carry its weight with me. Now the lives of those who are queer and Latina/o have changed – fueled with surveillance and concerns, never taking a temporary safe space for granted. Queer-Orlando-América is thus a “here and now” that has changed the contours of what “queer” and “America” were and are. Queer has now become less White – in your imaginary (we were always here). América now has an accent (it always had it – you just failed to notice). Violence in Orlando did this. It broke your understanding of a norm and showed you there is much more than the straight and narrow, or the Black and White “America” that is segmented into neatly organized compartments. In that, Orlando queers much more than those LGBT Latinas/os at the club. Orlando is the rupture that bridges a queer Brown United States with a Latin America that was always already “inside” the US – one that never left, one which was invaded and conquered. Think Aztlán. Think Borinquen. Think The Mission in San Francisco. Or Jackson Heights, in NYC. Or the DC metro area’s Latino neighborhoods. That is not going away. It is multiplying.

As the week advanced, and fathers’ day draws closer, I have already noticed the reordering of the news, a staged dismissal so common in media outlets. Those queer and Brown must continue to raise this as an issue, to not let the comfort of your organized, White hetero-lives go back to normal. You never left that comfort, you just thought about “those” killed. But it was “Latino night” at a gay club. I do not have that luxury. I carry its weight with me. Now the lives of those who are queer and Latina/o have changed – fueled with surveillance and concerns, never taking a temporary safe space for granted. Queer-Orlando-América is thus a “here and now” that has changed the contours of what “queer” and “America” were and are. Queer has now become less White – in your imaginary (we were always here). América now has an accent (it always had it – you just failed to notice). Violence in Orlando did this. It broke your understanding of a norm and showed you there is much more than the straight and narrow, or the Black and White “America” that is segmented into neatly organized compartments. In that, Orlando queers much more than those LGBT Latinas/os at the club. Orlando is the rupture that bridges a queer Brown United States with a Latin America that was always already “inside” the US – one that never left, one which was invaded and conquered. Think Aztlán. Think Borinquen. Think The Mission in San Francisco. Or Jackson Heights, in NYC. Or the DC metro area’s Latino neighborhoods. That is not going away. It is multiplying.