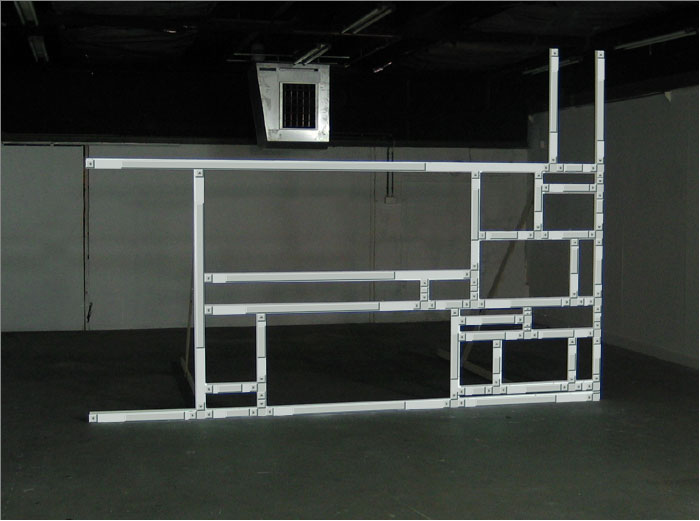

Jan Robert Leegte‘s scrollbars in physical space are another example of augmented reality art. More info and images here.

Jan Robert Leegte‘s scrollbars in physical space are another example of augmented reality art. More info and images here.

I’m a fan of artists using Google Earth or Street View images, such as Jon Rafman’s compelling Street View images or Google’s Street Art View. Here, check out Clement Valla’s “Postcards from Google Earth, Bridges” project. Google Earth renders bridges quite imperfectly, and when these images are shown together, they remind us that Google’s project is not a pure and perfect digital simulation of our world, but, instead, the creation of something new. Something that can be judged aesthetically on its own standards even if they are created as, to quote the artist, “the result of algorithmic processes and not of human aesthetic decision making.”

I’m a fan of artists using Google Earth or Street View images, such as Jon Rafman’s compelling Street View images or Google’s Street Art View. Here, check out Clement Valla’s “Postcards from Google Earth, Bridges” project. Google Earth renders bridges quite imperfectly, and when these images are shown together, they remind us that Google’s project is not a pure and perfect digital simulation of our world, but, instead, the creation of something new. Something that can be judged aesthetically on its own standards even if they are created as, to quote the artist, “the result of algorithmic processes and not of human aesthetic decision making.”

As readers of this blog know well, this new creation born out of the intersection of the physical and digital is what we refer to as “augmented reality.” Sometimes augmented reality is the reality we always find ourselves in: physical, but always and increasingly influenced by digitality. Sometimes this augmented reality is a collection of imperfectly rendered bridges. For me, Valla’s art provocatively reinforces this important theoretical conceptualization.

More augmented reality art: Augmented Ecologies; Siavosh Zabeti’s Facebook book; Michael Tompert’s photography of destroyed Apple products; Aram Bartholl’s embedding USB sticks into public spaces. And all of Valla’s “Postcards from Google Earth, Bridges” are found here.

This book brings together a selection of key tweets in a compelling, fast-paced narrative, allowing the story of the uprising to be told directly by the people in Cairo’s Tahrir Square.

The prosumer is one who produces what they consume and visa versa. Tweets from Tahrir places traditional consumers of content, the many faces in the crowd, as also content producers. What utility does having these tweets in book form have?

Jeff Jarvis wrote a critique of having multiple identities on social media (find the post on his blog – though, I found it via Owni.eu). While acknowledging that anonymity has enabled WikiLeaks or protestors of repressive regimes, he finds little utility for not being honest on social media about yourself. Jarvis argues against having multiple identities, e.g., one Twitter account for work and another for friends or a real Facebook for one group and a fakebook (a Facebook profile with a false name) for another.

Jeff Jarvis wrote a critique of having multiple identities on social media (find the post on his blog – though, I found it via Owni.eu). While acknowledging that anonymity has enabled WikiLeaks or protestors of repressive regimes, he finds little utility for not being honest on social media about yourself. Jarvis argues against having multiple identities, e.g., one Twitter account for work and another for friends or a real Facebook for one group and a fakebook (a Facebook profile with a false name) for another.

Jarvis argues that the problems associated with presenting yourself in front of multiple groups of people (say, your mother, boss, best friend, recent fling, etc) will fade away under a state of “mutually assured humiliation.” Since we will all have the embarrassment of presenting a self to multiple groups, we all will forgive each other so that others will return the same favor to us. “The best solution”, Jarvis argues, “is to be yourself. If that makes you uneasy, talk to your shrink.” This is reminiscent of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg who stated “having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity,” or current Google CEO Eric Schmidt who said that “if you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.”

The obvious problem with this line of thinking is that the problems associated with displaying a single self in front of multiple populations is not “mutually” the same for all. Just as WikiLeaks or protestors often use anonymity to counter repressive and/or powerful regimes, we know that anonymity is also used by the most vulnerable and least powerful on the personal level as well. Jarvis misses the important variables of power and inequalities in his analysis.

Having a stigmatized and not always accepted identity can bring much conflict and pain if one displays the same to everyone. Fellow Cyborgology editor PJ Rey makes this point powerfully when he asks, “Have We Built a Society without Closets?” Take, for example, a gay teenager who cannot display their “real” self without fear of being financially and emotionally undermined by their parents. Or the woman who wrote an open letter to Google after the introduction of their Buzz service made her most frequent email contacts publically known which jeopardized her physical safety because of an abusive ex.

It is easy to argue for people to be “real” when their “real” identity is widely accepted. As danah boyd stated, “Zuckerberg and gang may think that they know what’s best for society, for individuals, but I violently disagree. I think that they know what’s best for the privileged class.” It is easy to argue that the stigmas associated with presenting yourself to different populations will erode, but the important question is eroding for whom? Stigma will not erode for everyone the same, a point I previously made about “Facebook skeletons,” arguing that embarrassing bits of your social media presence are forgiven faster for men than women.

This issue will be the topic of two of my forthcoming posts here on Cyborgology. One on inauthenticity and the Fakebook and another on this reoccurring privileging of some “real” or true authentic self. I found this same issue when critiquing cyborg-anthropologist Amber Case and again here in the line of thinking Zuckerberg, Schmidt and Jarvis promote that serves to take down the door to closets so important for both self-protection as well as identity play. Stay tuned for a Foucauldian critique that acknowledges the highly limiting nature of this obsession of some fictional “true” self at the expense of identity play both on and offline. The norm that needs changing is not for people to stop playing with identity, as Jarvis argues, but for that playfulness to be better accepted and promoted.

The Cyborgology editors are throwing a conference on April 9th called Theorizing the Web. Leading up to the event, we will occasionally highlight some of the events taking place. I will be presiding over a paper session simply titled “Cyborgology” and present the four abstracts below. As readers of this blog already know, we view cyborgology as the intersection of technology and society. We define technology more broadly than just electronics, but also to things like architecture, language, even social norms. And the four papers on the Cyborgology panel offer a broad scope of what cyborgology is and how it can be used.

The Cyborgology editors are throwing a conference on April 9th called Theorizing the Web. Leading up to the event, we will occasionally highlight some of the events taking place. I will be presiding over a paper session simply titled “Cyborgology” and present the four abstracts below. As readers of this blog already know, we view cyborgology as the intersection of technology and society. We define technology more broadly than just electronics, but also to things like architecture, language, even social norms. And the four papers on the Cyborgology panel offer a broad scope of what cyborgology is and how it can be used.

First, we have David Banks’ paper titled, “Practical Cyborg Theory: Discovering a Metric for the Emancipatory Potential of Technology.” David discusses what theoretical cyborgology is and what it can do. Bonnie Stewart offers a discussion of the social-media-using-cyborg as a sort-of “branded” self in her paper, “The Branded Self: Cyborg Subjectivity in Social Media.” Bonnie pays special attention to, in true cyborgology fashion, the way in which digital and physical selves interact and blur together. Next, Michael Schandorf argues that Twitter norms are akin to the non-speech gestures we make while talking (e.g., like moving our hands). What makes his paper, titled, “Mediated Gesture of The Distributed Body,” so appropriate for the Cyborgology panel is Michael’s focus on the physically and socially embodied nature of digital communication. Even digital communication does not exist alone in cyberspace but in an “augmented reality” at the intersection of atoms and bits. Last, Stephanie Laudone’s paper, “Digital Constructions of Sexuality,” empirically describes how sexuality is both affirmed and regulated on Facebook. This, again, highlights the embodied nature of Facebook while looking at how digital space operates differently than physical space.

Find the four abstracts below. Together, they will make for an exciting panel. We invite everyone to join us at the conference in College Park, MD (just outside of Washington, D.C.) on April 9th. And let’s start the discussion before the conference in the comments section below. Thanks!

David Banks (@DA_Banks), “Practical Cyborg Theory: Discovering a Metric for the Emancipatory Potential of Technology”

The cyborg, an entity that is part organism and part machine, is an increasingly important topic in the social sciences. The word gained traction as a metaphor, when Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” gained popularity in the late 80s. The manifesto challenged several contradictions between what feminists said about how women are treated by society, and what it meant to be a woman. For example, women are often considered more naturalistic, or “closer to the Earth,” while men enjoyed a more privileged position as producers of culture and the curators of civilization’s life-sustaining technology. Haraway’s manifesto rejects this idea, and instead tells us that we are all part nature and part culture. To live in a world of cyborgs, meant to live in a post-gender age in which humanity transcended the nature/culture divide and all individuals were users of technology as well as living organisms within nature.

The nature/culture divide is so pervasive that you probably think about it every day and not even notice. If I say, “organic food” you might think about apples from a bucolic orchard that have been handpicked by a farmer whose family has tilled the land for generations. The apple is part of a sort of unfettered nature, where technology has not altered the apple in any way. Contrast that apple with a conventional one, grown in a huge farm owned by agribusiness. It has been genetically altered in some industrial lab, and then sprayed with chemical insecticides. To think about both of these hypothetical apples in cyborg terms- means to acknowledge that the organic apple is the result of hundreds of years of selective breeding by humans, and that the conventional apple is still the fruit of a plant. The nature seems outside of the human, whereas the cultural is seen as an intervention by humans to alter the natural state of things.

We are all cyborgs in this way. Whether we are altering our bodies with makeup, wearing the symbols of our cultural heritage, or using an iPhone, we are simultaneously natural and cultural. Once we recognize this, it is difficult to make the distinction between what is “nature” and what is “culture.”

But is any of this useful? What does the cyborg self do for us? I think it can do a lot. In the apple example, it can help us talk about our food supply. What had seemed like an irreconcilable debate between those that prefer unfettered nature, and those that demand the convenience and reliability that technology can provide, suddenly becomes a spectrum of possibilities. Considering a completely different kind of apple for a moment: How does the iPhone augment the human body? To what extent is the user empowered by its ability to retrieve information? How are they constrained by restrictive use policies and content curation? The cyborg perspective helps us answer these questions without getting caught up in traditional distinctions of the “natural” and the “artificial.” Our cyborg selves are doing the same things we’ve always done. We search for good food, shelter, and companionship- but instead of smoke signals, its SMS messages; instead of pamphlets its Facebook groups. The cyborg can help us focus on the content of the problem, and see the technology for what it is: the other half that has always been there.

Bonnie Stewart (@bonstewart), “The Branded Self: Cyborg Subjectivity in Social Media”

My work takes up the question of who we are when we’re online. Participatory, reputation-focused online platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and blogs allow people to perform their learning, their sociality and interests, their narrative histories and their minutiae in newly public, connected ways. The premise of my research is that these ongoing interactive performances open up new conceptions of self and subjectivity, and create new horizons and challenges within the field of education.

Donna Haraway called her original A Manifesto for Cyborgs (1991) an “ironic political myth”. In the late 20th century, she named the cyborg as our ontology, a representation of our societal and cultural politics. In reviving her cyborg for the era of social media, I explore its mythic potential for the relational and participatory knowledge-making sphere of social media, where new stories of self are told and reflected. With a deep bow to Haraway, my exploration of the branded cyborg subject aims to be an ironic educational myth for the 21st century.

I think of all of us using social media as branded selves, cyborgs whose online and offline lives blur. We are cyborgs because we are hybrids; because our “real lives” play out in part in cyberspace. We are branded because the cyberspace environment operates by branding – and socializing – all who enter: social, financial, and cultural capital are as central to the circulation of power and knowledge online today as the technologies and the human networks which form its infrastructure. The identities through which we connect with others and engage in the shared creation/consumption cycle that marks the social media economy are branded identities, even if we never monetize our brands.

Informal polls of cyborg subjects who live large portions of their lives online suggest that they generally consider their digital identities simply as extensions of themselves rather than as anything separate and distinct. I utilize Judith Butler’s notion of performativity to examine the constitution of subjectivities both online and off: those of us who become cyborg are always already subjects, yet the life that our stories and selves take on in cyberspace impacts our everyday lives in turn. Thus there is no dualistic divide between digital self and embodied self.

Nonetheless, the digital performance of identity warrants specific focus. The conventions and operations surrounding online interactions are not the same as in so-called “real life,” even when cyborg subjects try to conduct ourselves similarly across environments. The speed of connections, the different structures governing hierarchical relations, and the different conventions and etiquettes of online and offline life alter the subject positions that the environments create and privilege. The discursive field of social media – which my work posits as the site or stage on which the cyborg self performs and circulates – deviates from that of the broader culture. Some things are more speakable online than in real life, and the ways in which people interact and build knowledge within networks differs. My work treats our digital identities as offshoots of previously existing subjectivities, learning and engaging in augmented digital environments but always in a recursive relationship with our embodied selves.

Michael Schandorf (@mschandorf), “Mediated Gesture of the Distributed Body”

The predominant use of social media for “keeping in touch,” for what scholars call “phatic” communication, rather than for substantive dialogue and information exchange has been noted by a number of commentators, academic and otherwise. Using the specific example of microblogging (Twitter), I argue that the forms and conventions of social media communication are highly analogous to co-speech gesture – spontaneous movements of the hands that we all make while talking. Such gestures, and nonverbal communication generally, are the fundamental forms of phatic communication, expressing emotion and indicating and performing social bonds. Furthermore, co-speech gestures are highly integrated with the production of language: language and gesture are co-produced, involve contiguous and over-lapping areas of the brain, and together provide a basis for both intra-personal communication and social cognition. Communication is cognition; thought is both a physical and a social process. By making an analogy between gesture and social media forms, I argue, we can ground the study of digital technologies in the body rather than getting lost in the abstractions of the technologies themselves. Brian Rotman’s (2008) Becoming Beside Ourselves: The Alphabet, Ghosts, and Distributed Human Being makes a similar argument, positing a third modality of self arising from our digital technologies, much like the “linear” or “typographic” or “scriptive” modern self is argued to have arisen from the invention of writing (e.g. Marshal McLuhan): alongside the oral and the scriptive/typographic comes the “parallel and distributed,” the “networked self.” As Timothy Lenoir writes in his forward to Becoming Beside Ourselves, “Not only is thinking always social, culturally situated, and technologically mediated, but individual cognition requires symbiosis with cognitive collectivities and external [cultural] memory systems to happen in the first place” (p. xxvii). The point is not to further emphasize what is new and different about digital technologies and social media, but instead to reinforce the physically embodied and social preconditions of human communication and cognition, even in cyberspaces.

Stephanie Laudone, “Digital Constructions of Sexuality”

The social networking site, Facebook, operates a space where users can construct digital expressions of sexuality and in doing so, can reclaim and reaffirm their sexuality and sexual identities. At the same time, Facebook and the Facebook community often work together to publically regulate expressions and constructions of sexuality. This work draws on a sample of adult community members and parents, ages 35 to 50, drawn from a racially diverse, middle class neighborhood in a northeastern U.S. city, as well as content analyses of participants’ Facebook profiles and netnographic observations of Facebook.

These data show that participants who are mothers often use Facebook as a way to explore and reconnect with sexuality and sexual identities that have been suppressed since becoming parents. For some mothers, Facebook reconnects them with a sense of sexuality that they felt more connected with before becoming parents. In some ways, Facebook is a place where participants can feel sexually attractive again through the support of their Facebook community and friends.

While Facebook offers a seemingly free space for women to explore and reclaim their sexualities, it is also a space where sexuality is regulated and controlled. Users create normative conceptions of sexuality through their profiles, as well as interactions with others. Participants discussed the regulation of sexuality within their romantic relationships and between partners on Facebook. Sexuality and relationships are not only monitored by the partners in the relationship, but also by others within their Facebook networks.

Thus, while Facebook offers a place for users to reaffirm and validate their sexual identities and sexuality, it is also a space where users regulate sexuality, their own and others. Facebook and the Facebook community together create a discourse on what sexualities can be expressed and how sexualities can be expressed, resulting in a sort of public regulation of sexuality. Facebook is different from other media representations of sexuality, because instead of just receiving these images, the entire community can participate in this regulation of sexuality on Facebook. Thus while for some, Facebook is a space to reaffirm and recreate sexual selves, it is also a space that regulates which of those sexual selves can be reaffirmed and recreated, and how.

Zygmunt Bauman (pictured above) provides a famous liquidity metaphor that I find infinitely useful for thinking about the Internet. My previous post on Wikileaks and our Liquid Modernity outlins how the Internet and digitality are making information more fluid, nimble and difficult to contain. Using the liquidity metaphor, I argue that WikiLeaks is an example of increasingly liquid and leak-able information.

Zygmunt Bauman (pictured above) provides a famous liquidity metaphor that I find infinitely useful for thinking about the Internet. My previous post on Wikileaks and our Liquid Modernity outlins how the Internet and digitality are making information more fluid, nimble and difficult to contain. Using the liquidity metaphor, I argue that WikiLeaks is an example of increasingly liquid and leak-able information.

I further argue that “heavy” structures need to become more porous; that is, allow for some amount of liquidity in order to withstand the torrent of contemporary fluidity. Julian Assange argued that his WikiLeaks project will cause governments to become more secretive, or, using Bauman’s metaphor, those structures become more solid and thus become washed away by seeming out of date to current, more liquid, realities. I believe we saw a scenario just like this play out in Egypt.

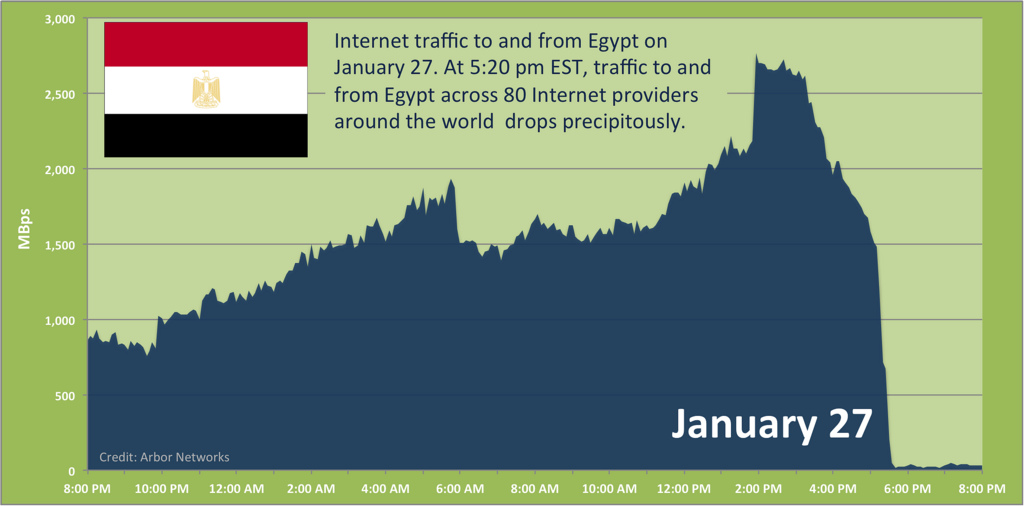

Armed with those great tools of liquid information, Egyptian protesters organized themselves, in part, using social media. And, as the chart above demonstrates, the spout of liquid information was literally shut off. While the fact that Egypt was even able to turn off the Internet signals the limits of liquidity, the aftershock resonates clearly: erecting barriers and becoming more solid (less-porous) served to make a government already in a legitimation crisis seem even more antiquated and repressive.

Too solid, the structure of the Egyptian government was even less prepared to withstand the rising tide of a liquid generation. Shutting down the Internet did not slow protests, but enflamed them. Unable to bend, the structure was largely washed away.

Governments across the globe are being faced with a decision: to further solidify or become more porous. On one hand, a government that cannot provide flowing digital information in today’s liquid world looks immediately repressive. On the other, allowing the free flow of information might foster dissent (for instance, China has a powerful “solid” “Golden Shield” around web traffic that allows it to more tightly control information – more on China and this issue here). This dilemma (more specifically, “the dictator’s dilemma”) is summed in this New York Times quote from a senior state department official,

Some may take measures to tighten communications networks,” said the official, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Others may conclude that these things are woven so deeply into the culture and commerce of their country that they interfere at their peril. Regardless, it is certainly being widely discussed in the Middle East and North Africa.

As the Jasmine Revolution continues to march on, this dilemma of liquidity continuously plays out (Libya, for example, removed itself from the Internet). The theoretical lens of liquidity helps illustrate why becoming tighter, more repressive and draconian (and thus more solid) makes for increasingly vulnerability to the rising torrent of liquidity.

The Cyborgology editors, again, appear on WYPR (Baltimore’s NPR affiliate). Listen to the audio here. We discuss “cyber-support”, something we have touched on before.

The Cyborgology editors, again, appear on WYPR (Baltimore’s NPR affiliate). Listen to the audio here. We discuss “cyber-support”, something we have touched on before.

Social media sites like Facebook and Formspring have created new forums for bullying—you may have heard the word “cyberbullying” thrown around.

But social media also provides an opportunity for marginalized groups to gather for support—and occasionally to fight back. Our social media gurus Nathan Jurgenson and P.J. Rey call this “cybersupport.” You can see it at sites like Harassmap, the“3,000 Campaign” against sexual assault, and iHollaback.

Today Nathan and P.J. join Sheilah to talk about this type of networking and the effects it can have—intended and unintended—in physical space.

Nathan Jurgenson and P.J. Rey are Ph.D. candidates in sociology at the University of Maryland, and they blog at Cyborgology.

Also, there will be a panel on so-called cyber-support at the Theorizing the Web conference we are throwing on April 9th.

Twitter users, likely from outside of China itself, are calling for people to “stroll” in Chinese public areas. The strolling protestors are not to carry signs or yell slogans, but instead to blend in with regular foot traffic. Chinese officials will not be able to identify protestors who themselves can safely blend in anonymity. [Edit for clarity: the idea is that foot traffic will increase in the announced area, but officials won’t know which are the protesters.]

Twitter users, likely from outside of China itself, are calling for people to “stroll” in Chinese public areas. The strolling protestors are not to carry signs or yell slogans, but instead to blend in with regular foot traffic. Chinese officials will not be able to identify protestors who themselves can safely blend in anonymity. [Edit for clarity: the idea is that foot traffic will increase in the announced area, but officials won’t know which are the protesters.]

This tactic is reminiscent of those French Situationist strategies of May ’68 to create chaos and disorder (note that strolling is akin to, but not exactly the same as, DeBord’s practice of “the derive“). The calls to “stroll” have had impact in China with the government shutting down public spaces and popular hangouts. Even a busy McDonald’s was closed. These gatherings announced over Twitter have been highly attended by many officials, police and media, but, importantly, not by many protestors themselves.

This is slacktivism at its best. If this slacker activism is often defined by both a grounding in digitality and a lack of real on-the-ground effort, then a Twitter protest-without-protesters is slacktivism par excellence. This latest slacktivist technique has been highly effective at creating a deep psychological worry for a Chinese government unsure where a protest might happen and unable to identify which individuals are actually protesting.

This is one prong of the larger “Jasmine Revolution” hinted at in China, that, like those occurring in the Arab world, are often organized and implemented using social media tools. And, as I previously wrote, these tactics are not “Facebook” or “Twitter Revolutions,” but represent a larger augmented revolution, one that takes into account both how to effectively use digitality (here, the expert use of Twitter) in conjunction with utilizing physical space (the tactic of blending and strolling).

This is one prong of the larger “Jasmine Revolution” hinted at in China, that, like those occurring in the Arab world, are often organized and implemented using social media tools. And, as I previously wrote, these tactics are not “Facebook” or “Twitter Revolutions,” but represent a larger augmented revolution, one that takes into account both how to effectively use digitality (here, the expert use of Twitter) in conjunction with utilizing physical space (the tactic of blending and strolling).

Foucault was right that power is enacted most perfectly when it needs not be enacted at all -e.g., that the power of the panopticon was that the guards need not actually be in the tower (interestingly, Talcott Parsons argued the same, but viewed this as utopian opposed to Foucault’s dystopian take). In this latest Chinese example, resistance to power -protest- is being enacted without being enacted at all. Perhaps the most perfect protest is one that entices fear in a regime without there actually being a protest or protesters in the first place. Or is the non-protest precisely the type officials should fear the least?

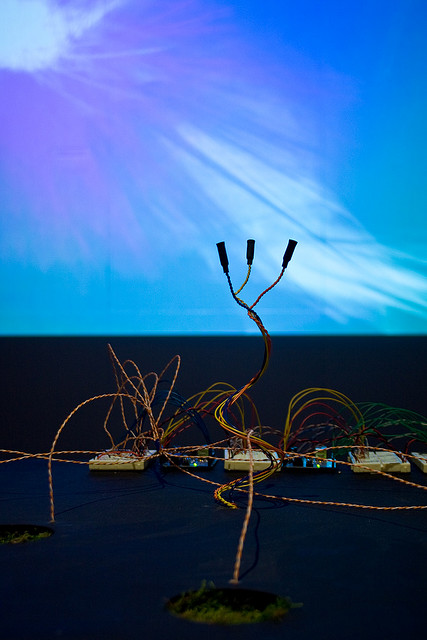

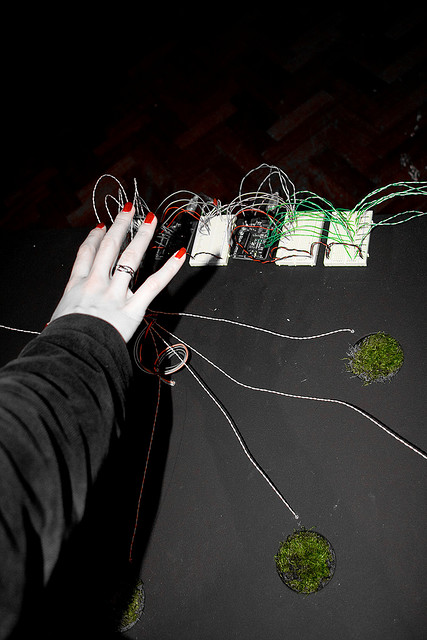

The integration of biological and technological systems in the design of an interactive human interface is explored through an installation where plants rigged up with sensors provide a kinesthetic user experience based on movement, touch, sound and light. Human interaction with the system affects an algorithmic projection and soundscape.