This is part of a series of posts highlighting the Theorizing the Web conference, April 14th, 2012 at the University of Maryland (inside the D.C. beltway). It was originally posted on 4.6.12 and was updated to include video on 6.22.12. See the conference website for additional information.

The issue of self documentation is increasingly fertile ground for theorizing the intersection of the digital and the material, illustrating how our identities are increasingly mediated by new technologies and “digital” forms of sociality. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest (as relatively new forms of sociality) produce requisite changes in our self concepts. In the digital era, identity becomes a project of coordinating, collecting, and curating; self presentation becomes a project of self documentation.

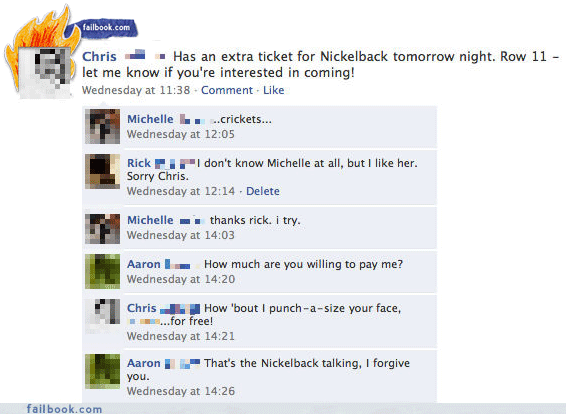

Each of these authors acknowledges the paradigmatic changes new technology (especially social networking sites like Facebook) has introduced into our self concepts. For example, Aimée Morrison looks at how norms are created, encouraged, and enforced in the digital realm of Facebook. The Facebook status update field has gone through several permutations, reflecting changing expectations and norms regarding self presentation and self documentation on this popular social networking site. Somewhat differently, Rob Horning addresses issues of power and control in the promulgation of new forms of sociality. More specifically, Horning discusses Facebook’s role in socializing users into the “digital self,” or the self as curated project. Self documentation is integral to the rise of the digital self and the destruction of the inner/private self. In addition, Jordan Frith reflects on how social media incorporates emerging GPS technology into location based social networks (LBSN) like Foursquare. Drawing from qualitative interviews with over 35 Foursquare users, Frith analyzes the impact of this LBSN on both self-presentation and self-documentation practices.

Finally, social media and the ability to self-document also changes our conception of time. As Nathan has argued, “Social media increasingly force us to view our present as always a potential documented past” (Jurgenson, 2011). In this vein, Sam Ladner addresses the proliferation of digital calendaring (MS Outlook, Google Calendar) and resultant changes such technology engenders to our conceptions and use of time. Digital calendars create new affordances but also new risks in time management.

[Paper titles and abstracts after the jump.]

Rob Horning (@marginalutility) – “Facebook as the ‘Projective City'”

In a short paper, I compare Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s recent letter to investors that accompanied its IPO to Boltanski and Chiapello’s description of “”the projective city”” in The New Spirit of Capitalism to demonstrate how social media companies are helping naturalize the so-called post-Fordist network society. They have broadened the reach of the ideology that privileges flexibility over security and renders social life as a series of entrepreneurial risks rather than a respite from work-related depletion. Facebook has exported management techniques developed for corporate streamlining and now explicitly seeks to implement them on the whole of its nearly billion users.

In a short paper, I compare Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s recent letter to investors that accompanied its IPO to Boltanski and Chiapello’s description of “”the projective city”” in The New Spirit of Capitalism to demonstrate how social media companies are helping naturalize the so-called post-Fordist network society. They have broadened the reach of the ideology that privileges flexibility over security and renders social life as a series of entrepreneurial risks rather than a respite from work-related depletion. Facebook has exported management techniques developed for corporate streamlining and now explicitly seeks to implement them on the whole of its nearly billion users.

Facebook prompts us to reconceive sociality in terms of provisional projects and our place in society as a tactical point on an ever-shifting “social graph,” while reshaping the values that support our perception of what defines and justifies effort in nonprofessional relationships. The social media space becomes an arena for project-making, and involvement with projects come to dictate the status of any given relationship. These projects, as Boltanski and Chiapello argue, form the basis for elaborating the network to ever greater degrees, providing social-media companies with powerful incentives to try to remake friendship in the project mold. Thus in Facebook’s public rhetoric and in the architecture of its service, activity for activity’s sake is seen as a behavioral norm and novelty is held to be intrinsically satisfying; these come at the expense of older ideals of intimacy and privacy.

At the same time, identity becomes an explicit product of one’s position and activity in a network rather than a quality of the self that one seeks to express within the network. This affords companies like Facebook a proprietary interest of sorts in its users’ identities. Their work to continue to affirm their identity and presence in Facebook becomes the company’s data product. Thus Facebook has incentive to give ideological support to a post hoc conception of identity, a “data self” that emerges after one generates a sufficient quantity of recordable and processable information and is recognized as the truth about oneself, as opposed to previous conceptions that emphasized the possibility of uncovering a unique pre-existing self through various acts of self-actualization. By helping society discard the notion of the inner self that can be discovered once the more basic needs of security are met, Facebook is creating social conditions under which a precarious self — burdened with social risk, uncertain prospects and lacking in ontological security — becomes more tenable and tolerable for subjects.

Sam Ladner (@sladner) – “Digital Time: The Technological Transformation of the Calendar”

We stand at the cusp of a major shift in how we organize and understand time. Technological change profoundly affects time reckoning (Heidegger, 1954) and new ways to reckon time are often harbingers of new ways to order social life (Thompson, 1967). This paper will explore how contemporary web-based technologies affect calendaring and time reckoning in general. Like many other social phenomena, time reckoning is rapidly becoming a “digital” phenomenon. Time is a very fundamental “typification” of social life (Berger & Luckman, 1966, p. 27), yet we have very little theoretical work on the socio-cultural significance of calendaring (Postill, 2002). Millions of people use Microsoft Outlook and Google Calendar (Google Inc, 2010). These very common web-based tools represent time in significantly different ways than traditional analogue calendars in that they make appointments digital. Digital artifacts can be ordered, and re-ordered at will, and easily “mashed up” with other artifacts. In this paper, I trace three significant trends in calendaring.

We stand at the cusp of a major shift in how we organize and understand time. Technological change profoundly affects time reckoning (Heidegger, 1954) and new ways to reckon time are often harbingers of new ways to order social life (Thompson, 1967). This paper will explore how contemporary web-based technologies affect calendaring and time reckoning in general. Like many other social phenomena, time reckoning is rapidly becoming a “digital” phenomenon. Time is a very fundamental “typification” of social life (Berger & Luckman, 1966, p. 27), yet we have very little theoretical work on the socio-cultural significance of calendaring (Postill, 2002). Millions of people use Microsoft Outlook and Google Calendar (Google Inc, 2010). These very common web-based tools represent time in significantly different ways than traditional analogue calendars in that they make appointments digital. Digital artifacts can be ordered, and re-ordered at will, and easily “mashed up” with other artifacts. In this paper, I trace three significant trends in calendaring.

First, I will outline how the calendar, like the clock before it, has become increasingly a “personal” artifact. This shift has brought with it significant contestation and a transformed the personal calendar into a symbol of “upward mobility.” Second, I sketch out the three ways in which the digital calendars differ from analogue ones: their apparent “bottomlessness,” their networked nature, and the ease with which they are altered. And finally, I will show how the digitization and personalization of calendaring are intersecting in the rise of personal mobile calendars on smartphones. I will then discuss the implications of these mobile, personal, digital calendars. How might they change temporal experience? What potential changes to social organization could they create?

Aimée Morrison (@digiwonk) – “The Affordance of Facebook: Autobiography and the Changing Status Update Field”

Fundamentally, social network sites invoke, compel, and shape (and are in turn themselves reshaped by) autobiographical discourse from individual users. Employing the theory of “affordance” drawn from visual perception studies (Gibson; Norman; Hutchby; Graves), as well as that of “coaxing,” drawn from auto/biography studies (Smith and Watson Getting a Life; Smith and Watson Reading; Poletti) this paper investigates how users figure out what to do, and how to do it, when confronted with the interface of one particular social network site, Facebook.

Fundamentally, social network sites invoke, compel, and shape (and are in turn themselves reshaped by) autobiographical discourse from individual users. Employing the theory of “affordance” drawn from visual perception studies (Gibson; Norman; Hutchby; Graves), as well as that of “coaxing,” drawn from auto/biography studies (Smith and Watson Getting a Life; Smith and Watson Reading; Poletti) this paper investigates how users figure out what to do, and how to do it, when confronted with the interface of one particular social network site, Facebook.

Much of the scholarly investigation into “”social network sites”” (boyd and Eliison) has, understandably enough, focused on the social and the network aspects: that is, how do people interact with one another in these spaces, and how is the boundary or membership of the networks and its social norms determined and policed (see Papacharissi, ed. 2011 for a collection of essays on this topic; Baym 2010 for an extended example)? But how do individual users know what to do, how to interact, what to say, when confronted with the site? The shifting affordance of the status update feature, I suggest, coaxes and coaches users in what kinds of actions are expected of them, in what kind of length, and using what kinds of extra, multimedia materials.

Since Facebook’s founding in 2004, the interface between service and users has changed many times: early versions of the site mainly prompted users to comment on other people’s walls (dialogue, public speech), with static profiles displayed; later versions of the status update shaped and invited particular kinds of disclosures. For example, an early interface featured a very small textbox and the prompt: “Aimée Morrison is:” inviting some kind of ontological statements—happy? Hungry? Over time, the visible text box grew longer (inviting longer format statements) and shifted the prompt—What are you doing? What’s on your mind? And now, most simply, “Share.” As the status update interface and its user base matured, the interface became more sophisticated in its options: media buttons inviting web links, audio files, video clips, and even quizzes now sit atop (take priority over?) the blank box that awaits your text.

Where most scholarship deals with Facebook in the aggregate and in the mass, this paper argues for an examination of the more intimate relationship between individual user and software interface. The close reading methodology of the literary study of autobiography meshes well with affordance-studies attention to means by which an individual perceiving subject makes sense of the possibilities of action in a given setting.

Such work is easily generalizable to other online contexts, and suggests, in Hutchby’s words a “”third path”” whereby a preponderance of investigation into macro-level activity online can be balanced against a minute attention to individual sites of interaction between users and interfaces.

Jordan Frith (@jhfrith) – “The Check-In as Marker and Mnemonic Device: Theorizing how Foursquare use Impacts Self-Presentation and Self-Documentation”

Two of the most important development in the communication technoscape over the last decade have been the adoption of Social Networking Sites (SNS) and the adoption of Internet-enabled mobile phones. SNS provide new ways for people to present themselves to others and document their lives, and smartphones enable people to stay constantly connected to the Internet and their social networks through mobile SNS applications. Smartphones also aid in the development of new forms of SNS, notably through the sharing of location information that takes advantage of the GPS and wireless triangulation capabilities built into these devices. These newer forms of SNS are called location-based social networks (LBSNs), and their popularity has increased over the last two years. Foursquare, the most popular LBSN, currently has over 12 million users.

Two of the most important development in the communication technoscape over the last decade have been the adoption of Social Networking Sites (SNS) and the adoption of Internet-enabled mobile phones. SNS provide new ways for people to present themselves to others and document their lives, and smartphones enable people to stay constantly connected to the Internet and their social networks through mobile SNS applications. Smartphones also aid in the development of new forms of SNS, notably through the sharing of location information that takes advantage of the GPS and wireless triangulation capabilities built into these devices. These newer forms of SNS are called location-based social networks (LBSNs), and their popularity has increased over the last two years. Foursquare, the most popular LBSN, currently has over 12 million users.

Drawing from data derived from 36 interviews and 9 months of ethnographic research with Foursquare users, this presentation theorizes how Foursquare usage impacts both self-presentation and self-documentation. On Facebook, people shape their presentation of self through the friends in their network, their status updates, their likes and dislikes, and the images they share. On Foursquare, they do so mostly through their mobility. By choosing to check-in to some places and share their location with friends, they are “writing themselves into being” (boyd, 2006) through their physical mobility. Drawing from my data, many Foursquare users, put a great deal of thought into how they present themselves through Foursquare, using a number of different approaches to highlight certain parts of themselves through their decisions about where to check-in. With the increasing growth of location-based services, it is important to understand how physical mobility can play an integral role in how people present themselves to others through mobile applications.

Equally interesting, my data reveals that many of my participants use Foursquare as a sort of “life logging” tool that documents their experiences. They are often selective about the places they check-into, not because of concern over how they present themselves to others, but because of concerns about how they present their present self to their future self. For example, the service “Foursquare and Seven Years Ago” sends people an email each day telling them where they checked-in on that day last year. This service works as a mnemonic device, linking memory to one’s past location, reminding users of the experiences they enjoyed. Because of Foursquare’s role as a mnemonic device, people selectively choose where to check-in based on where they want to remember in order to not “pollute” their data set.

This presentation will examine these areas and use my data to theorize how self-presentation and self-documentation occur through Foursquare use. Considering the growing popularity of Foursquare and similar services, researchers must begin to think through the new affordances of the mobile Internet and this presentation will be a step in that direction.

Bishop’s (2010:20) “taxonomy” of the dead” is a useful for articulating the different conceptualizations of the zombie as it has appeared in film. In my opinion, however, the zombie can be reduced to three main types: the somnambulist (ie: mind control slave-zombie), the cannibalistic corpse (ie: undead eaters), and the infected living (eg: the “rage virus” of 28 Days Later).

Bishop’s (2010:20) “taxonomy” of the dead” is a useful for articulating the different conceptualizations of the zombie as it has appeared in film. In my opinion, however, the zombie can be reduced to three main types: the somnambulist (ie: mind control slave-zombie), the cannibalistic corpse (ie: undead eaters), and the infected living (eg: the “rage virus” of 28 Days Later).