If you were a little girl at some point in the last century, the odds are good that you played with paper dolls. They’ve been around for a long time—from 9th Century Japanese origami figurines and pre-Christian Balinese puppets to the more familiar 18th Century European varieties that feature a paper cut out of a female figure and various clothing items and accessories to place upon the body. This type of paper doll has remained popular throughout the 20th and 21st Centuries. In some ways, paper dolls democratized play for girls from families of little means; they’re cheap, and while doll play had been reserved for upper class children for centuries, once paper dolls could be mass produced they became widely available. In other ways, they stifle girls’ play by reinforcing limited tropes of femininity.

1950s Paper Doll, image credit Joe Haupt

Today there are also digital versions of paper doll games, geared toward both children and adults. They follow the same form as traditional paper dolls—a baseline figurine and a variety of clothing and accessories to place on the doll. Digital versions have many more options, and offer a variety of scenes or prompts that guide the player’s choices. For the last six weeks I’ve been playing one of these games, an app called Covet Fashion in which players enter challenges and style a look based on a scenario—fairy godmother, ice princess, brunch with the girls, that sort of thing. Users vote on looks, and high scores earn prizes like high quality designer replica handbags, dresses, shoes, and currency (diamonds) to spend in the game. It is, like most apps these days, a free game that allows in-app purchases, which inevitably means that players who spend money in the game receive higher scores, enter more challenges, and have more options for clothing and accessories.

My take on “Queen of the Evening Star.” Score: 3.25 out of 5

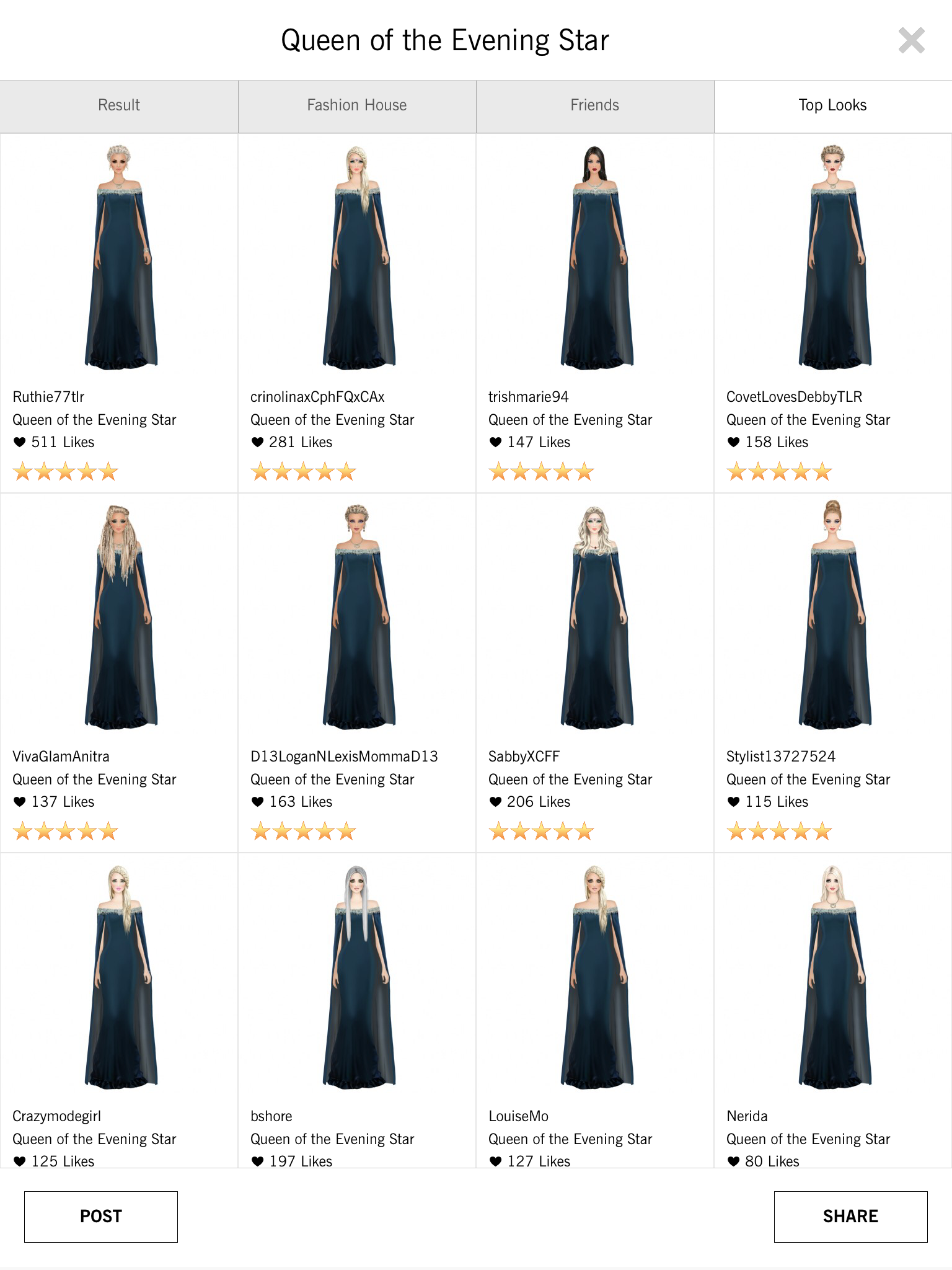

Top looks for “Queen of the Evening Star.” Note that the dress these models are wearing costs $3,400 in-game. Which is a lot. The dress I wore for the challenge is $495.

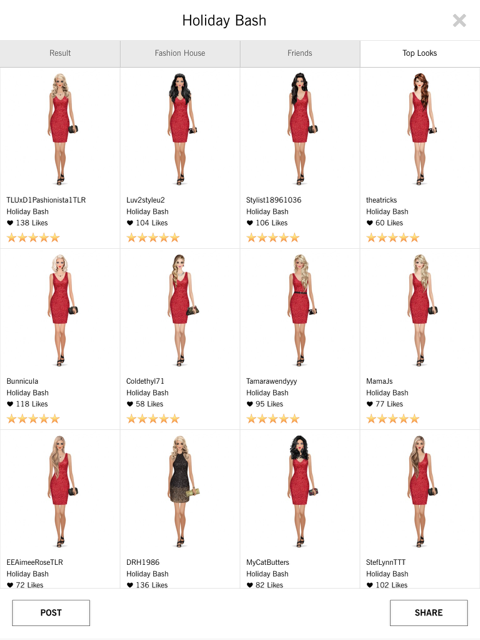

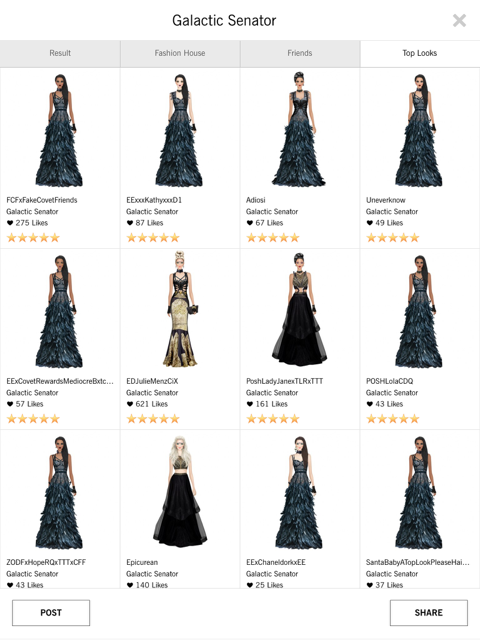

One of the first things I noticed about Covet is how white it is. Almost everyone is white. The models that pose for the challenge photo covers, the looks users create, and above all, the “top” looks that receive the most votes and likes, are by and large white. In the six weeks that I’ve been playing the game, I have checked the “top looks” for all 38 challenges I’ve entered. Out of hundreds of top looks, only one challenge featured a notable measure of diversity, with several darker models. This was also one of the few challenges for which the cover photo model was black. Of all the challenges I entered, I was unable to find a single black model who made it into the top looks.

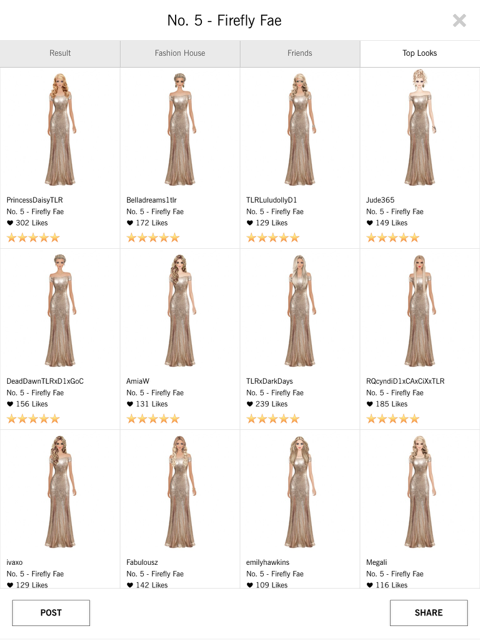

Top looks for three different challenges. Galactic Senator was more diverse than any other I encountered.

After a few days of playing the game, I decided to crunch the numbers. I wanted to see how well black models fared against white models. I collected two types of quantitative data for this analysis. First, I documented my scores on each look I submitted, alternating between black models and white models. There are five skin tones to choose from, and I stuck with the 2nd lightest and the very darkest, as they best reflected what I consider to be normative conceptions of white and black skin. I then averaged the scores for all of my looks, my black looks, and my white looks.

The second type of data collection examined voting. Each time a light skinned model was paired against a dark skinned model I noted the winner, which the game reveals after you vote. For this analysis I did not distinguish among the three light skin shades or the two dark skin shades—voting occurs too quickly, and it was difficult to distinguish among the five shades. Where there was a significant visible difference between them, I recorded the winner. Ties were omitted for the sake of simplicity in data collection and analysis.

Voting for the best golden rare mermaid.

Here are the results. The average score for my 38 challenges was 3.55. This is where I’ll note that I am apparently not great at fashion and should stick to my day job. For the 19 looks that featured white models, scores averaged 3.75. Black models averaged 3.36. When it came to head-to-head voting, I documented a total of 86 votes. White models won 55 times, and black models 31 times. That’s a 64% win rate for white models—nearly double the rate of black models. Paired with that fact that the top looks for each challenge were almost exclusively white, the conclusion of this data analysis is pretty straightforward. If you want to do well, win more prizes, and level up faster, go with white models.

These results resonate with at least three social forces that work to uphold racism and hegemony: racism in the fashion industry, implicit bias, and voting. Racism in the fashion industry is well documented. Minority (especially black) models are dramatically underrepresented, and designers even more so—just 2.7% of major international fashion designers are black. Prominent black models like Iman, Naomi Campbell, and Nykhor Paul have been outspoken about racism in the fashion world; nonetheless, little has changed over the last few decades. There were more prominent black fashion designers in the 1970s than there are today. In some cases, the percentage of white models at high-profile fashion events is growing.

With regards to the results of my analysis above, implicit bias likely plays an important role. Implicit bias is the sum of unconscious value judgments we make about certain populations. These may be associated with gender, sexual preference, body size, and of course race. Everyone has some degree of implicit bias—it’s a means of simplifying the world around us, allowing us to quickly evaluate people based on physical traits according to deeply engrained stereotypes. Implicit bias isn’t just limited to dominant groups: both black and white people tend to have implicit bias favoring white people, though the degree to which bias exists is stronger within the dominant group. And implicit bias may have dire consequences. For example, black boys as young as ten are perceived as older and less innocent than white boys of the same age, a factor which undoubtedly contributes to trends like the higher explusion rates for black students and, of course, increased likelihood for police violence and arrest.

Both factors are at play in Covet’s racist ranking outcomes, and when combined with the user voting system the results are compounded. As David Banks has noted, sites that rely on voting to produce content “will remain structurally incapable of producing non-hegemonic content because the ‘crowd’ is still subject to structural oppression.” In other words, the majority population tends to vote for things that reflect dominant discourses. As a result, whether we’re talking about a fashion app or the much more significant structures of governmental representation, minority populations do not hold as much sway over voting outcomes.

To covet is to yearn for something, to have a profound desire for some object. In the Bible it’s a sin, but under capitalism it is a key driver of consumerism and neoliberal identity maintenance. What do Covet users covet? Maybe it’s digital handbags or mini skirts, more diamonds to buy them with, and the awesome level 17 updo that seems to win every formal gown challenge. Maybe it’s recognition that you have style, that you’re fashionable, that given an enormous closet and enough diamonds you can craft a look that, if only in a digital world, other people recognize as desirable. But in order to obtain that which you covet, you must conform to the demands of white femininity perpetuated by so many industries, fashion included.

Comments 1

Nisha — January 13, 2016

Wow! All I can say is great post. It's was very well thought out and put together. I have been playing since 2013 and have also come to the idea of racism within the game. I rebelled and decided to only use darkest models for almost 2 whole seasons as well as change my username to reflect. Yes if you want a better chance of winning the game silently suggest you go white