Toilets are rife with politics. The things we do immediately before and after using the toilet are subject to all sorts of social and cultural power structures. Even getting a toilet in the first place can be swept up in the larger political debates about development and infrastructure investment. Everything from global finance to local political corruption can determine whether or not any given person on this planet gets to relieve themselves with comfort and dignity. It is a sad but true fact that an estimated 2.5 billion people do not have regular access to a toilet. Enter “The Nano Membrane Toilet” an invention from Cranfield University which uses state-of-the-art nano technology to make a toilet that does not require plumbing. Instead it needs batteries, regular servicing of complex and proprietary parts, and safe, dry removal of wax-coated solid waste. The decision to help fix this enormous problem is laudable but the Nano Membrane Toilet side-steps the real social and economic problems that keep people in unsanitary conditions. It might even create new, unintended sanitation problems. more...

Archive: 2016

The students in my Cultural Studies of New Media course are currently in the process of giving midterm presentations. The assignment was to keep a technology journal for a week, interview a peer, and interview an older adult. Students were to record their own and others’ experiences with new and social media. Students then collaborated in small groups to pull out themes from their interviews and journals and created presentations addressing the role of new and social media in everyday life.

Across presentations, I’m noticing a fascinating trend in the ways that students and their interviewees talk about the relationship between themselves and their digital stuff– especially mobile phones. They talk about technologies that are “there for you,” and alternatively, recount those moments when the technology “lets you down.” Students recount jubilation and exasperation as they and their interviewees connect, search, lurk, post, and click.

Listening to students, I am reminded that the contemporary human relationship to hardware and software is a decidedly affective one. The way we talk about our devices drips with emotion—lust, frustration, hatred, and love. This strong emotional tenor toward technological objects brings me back to a classic Louis C.K. bit, in which the comedian describes expressions of vitriol toward mobile devices in the wake of communication delays. For Louis, the comedic value is found in the absurdity of such visceral animosity toward a communication medium, coupled with a lack of appreciation for the highly advanced technology that the medium employs. more...

From the beginning of his entrance into the race, we’ve been clamoring to categorize Trump, to understand where he fits into the political and cultural landscape. First, he was a flash in the pan, an inevitable “also ran” with whom voters would quickly lose interest. He’s an “outsider,” despite his bragging about pulling the strings of politics through political donations for decades. He’s a fascist, hell-bent on whipping up national fervor to undermine democratic institutions and further bolster white supremacist power. And, of course, he’s a troll just trying to get voters riled up.

At Nancy Reagan’s funeral presidential candidate Hillary Clinton told MSNBC that the Reagans “started a national conversation about AIDS.” The response to that obviously false statement was swift and loud. Even Chad Griffin, the president of the Human Rights Campaign (which endorsed Clinton), tweeted “Nancy Reagan was, sadly, no hero in the fight against HIV/AIDS.” Clinton’s apology was posted to Medium the very next day. Picking a platform for a message goes a long way in picking the demographics of your message’s audience. The decision to use Medium for her apology was pitch perfect: older (and statistically more conservative) voters who watch cable news will see her praising the Reagans while younger voters who might turn to Medium to read the definitive take down of Clinton will find her own apology next to their favorite authors. More than just an apology though, the post goes on to give a small history of AIDS-related activism before going on to describe the present challenges facing those infected with HIV. More than an apology Clinton’s Medium post is an example of what I’m calling the “Explainer Candidate.” more...

CW: Cissexism, genital mutilation, penis shaming

“You know what they say about men with small hands?”

—Marco Rubio

Shame and genitals go together like peanut butter and jelly. The story of Adam and Eve tells us just how enduring this shame is. With knowledge came shame, and their nakedness and the differences of their genitals started a downward spiral of fear—fear of our own genitals, and fear of others. From mutilation of the labia and clitoris, to castration, to the disturbing obsession with the state of transgender and nonbinary people’s genitals, we have been conditioned to judge, manipulate, and even destroy these most sensitive body parts. And I really, really wish we would stop doing that. more...

Horse-race style political opinion polling is an integral a part of western democratic elections, with a history dating back to the 1800’s. Political opinion polling originally took hold in the first quarter of the 19th century, when a Pennsylvania straw poll predicted Andrew Jackson’s victory over John Quincey Adams in the bid for President of the United States. The weekly magazine Literary Digest then began conducting national opinion polls in the early 1900s, followed finally by the representative sampling introduced the George Gallup in 1936. Gallup’s polling method is the foundation of political opinion polls to this day (even though the Gallup poll itself recently retired from presidential election predictions).

While polling has been around a long time, new technological developments let pollsters gather data more frequently, analyze and broadcast it more quickly, and project the data to wider audiences. Through these developments, polling data have moved to the center of election coverage. Major news outlets report on the polls as a compulsory part of political segments, candidates cite poll numbers in their speeches and interviews, and tickers scroll poll numbers across both social media feeds and the bottom of television screens. So central has polling become that in-the-moment polling data superimpose candidates as they participate in televised debates, creating media events in which performance and analysis converge in real time. So integral has polling become to the election process that it may be difficult to imagine what coverage would look in the absence of these widely projected metrics. more...

I’ve dedicated a few essays to interrogating encryption and automation as a replacement for human judgement, politics, and inter-personal trust. Central to that argument is the observation that the replacement of institutions with technologies like blockchains are a rehashing of the arguments that set up those failing institutions in the first place. (You can read the full argument here and here.)

I’ve dedicated a few essays to interrogating encryption and automation as a replacement for human judgement, politics, and inter-personal trust. Central to that argument is the observation that the replacement of institutions with technologies like blockchains are a rehashing of the arguments that set up those failing institutions in the first place. (You can read the full argument here and here.)

This is important because the problems with have with our present institutions –how they are exploitable, alienating, or otherwise broken– may very well be exacerbated by these technologies, not solved by them. To drive this point home I have pulled a few excerpts from Max Weber’s writing on bureaucracy but I have replaced a few nouns (in bold) so that his references to human organizations are replaced by algorithms, blockchains, and other technologies. With just these few noun changes a 19th century German sociologist of modern statecraft turns into the next great TED talk:

An algorithm offers above all the optimum possibility for carrying through the principle of specializing administrative functions according to purely objective considerations. Individual tasks are allocated to heuristicfunctions who have specialized training and who by constant practice learn more and more. The ‘objective’ discharge of business primarily means a discharge of business according to calculable rules and ‘without regard for persons.’

Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of the files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs– these are raised to the optimum point with blockchain technology.

The tendency toward secrecy in certain development communities follows their material nature: everywhere that the power interests of the domination structure toward the outside are at stake, whether it is an economic competition of a private enterprise, or a foreign, potentially hostile polity, we find secrecy.

The absolute monarch is powerless opposite the superior knowledge of the crowd–in a certain sense more powerless than any other political head.

And here are the originals:

Bureaucratization offers above all the optimum possibility for carrying through the principle of specializing administrative functions according to purely objective considerations. Individual performances are allocated to functionaries who have specialized training and who by constant practice learn more and more. The ‘objective’ discharge of business primarily means a discharge of business according to calculable rules and ‘without regard for persons.’

Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of the files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs– these are raised to the optimum point in the strictly bureaucratic administration, and especially in its monocratic form.

The tendency toward secrecy in certain administrative fields follows their material nature: everywhere that the power interests of the domination structure toward the outside are at stake, whether it is an economic competition of a private enterprise, or a foreign, potentially hostile polity, we find secrecy.

The absolute monarch is powerless opposite the superior knowledge of the bureaucratic expert–in a certain sense more powerless than any other political head.

Facebook Reactions don’t grant expressive freedom, they tighten the platform’s affective control.

Facebook Reactions don’t grant expressive freedom, they tighten the platform’s affective control.

The range of human emotion is both vast and deep. We are tortured, elated, and ambivalent; we are bored and antsy and enthralled; we project and introspect and seek solace and seek solitude. Emotions are heavy, except when they’re light. So complex is human affect that artists and poets make careers attempting to capture the allusive sentiments that drive us, incapacitate us, bring us together, and tear us apart. Popular communication media are charged with the overwhelming task of facilitating the expression of human emotion, by humans who are so often unsure how they should—or even do—feel. For a long time, Facebook handled this with a “Like” button.

Last week, the Facebook team finally expanded the available emotional repertoire available to users. “Reactions,” as Facebook calls them, include not only “Like,” but also “Love,” “Haha,” “Wow,” “Sad,” and “Angry.” The “Like” option is still signified by a version of the iconic blue thumbs-up, while the other Reactions are signified by yellow emoji faces.

Ostensibly, Facebook’s Reactions give users the opportunity to more adequately respond to others, given the desire to do so with only the effort of a single click. The available Reaction categories are derived from the most common one-word comments people left on their friends’ posts, combined with sentiments users commonly expressed through “stickers.” At a glance, this looks like greater expressive capacity for users, rooted in the sentimental expressions of users themselves. And this is exactly how Facebook bills the change—it captures the range of users’ emotions and gives those emotions back to users as expressive tools.

However, the notion of greater expressive capacity through the Facebook platform is not only illusory, but masks the way that Reactions actually strengthen Facebook’s affective control. more...

In December 2015, the Democratic Party’s data infrastructure became the subject of fierce controversy. When it was publicly revealed that staffers of Bernie Sanders’s presidential bid breached rival Hillary Clinton’s voter data stored in NGP VAN’s VoteBuilder, this infrastructure, normally hidden from view, suddenly became a contested matter of concern. As the Democratic Party closed access to VoteBuilder for a period of time for the Sanders campaign, the candidate’s supporters, competitors to NGP VAN, and journalists publicly debated why the party had such control over voter data and, ultimately, the dangers that such centralization might pose for the party and the democratic process. I have spent the past decade studying platforms such as VoteBuilder. While the incident with Sanders raised a number of important issues, the Democratic Party’s data infrastructure, developed in the wake of the 2004 presidential election cycle, is a key reason for its well-documented technological advantages over its Republican rival that persisted at least through the 2014 midterm elections.

Before I go any further it is worth providing some background context from news reports on the Sanders data breach, with the caveat that I have no direct knowledge of and have not conducted original research on the incident. From journalistic reports, the basic facts behind the Sanders data breach of NGP VAN’s firewalls between campaigns seem clear enough. By exploiting a vulnerability in the NGP VAN system, staffers on the Sanders campaign pulled multiple lists of voters from the Clinton campaign’s voter data. According to news articles, this included data on things such as strong Clinton supporters in Iowa and New Hampshire, 24 lists in all. The DNC responded by temporarily suspending the Sanders campaign’s access to VoteBuilder, in effect preventing staffers from using their voter data less than two months out from the Iowa caucuses. more...

Donald Trump’s Twitter account is a huge part of his presidential campaign (Huge). The media quotes from it, his opponents try to score political points by making fun of it, and his fans / supporters constantly engage with its content. @realDonaldTrump is just that: a string of pronouncements that feel very (perhaps even a little too) real. As Britney Summit-Gil wrote back in December: “the beauty of Trump’s tweetability is that his fans don’t really care if he’s manicured or carefully crafted—it’s what they love about him. His tweets read just like his speeches sound. They’re off the cuff, natural, and engaging.”

I want to take a minute to dive into the powerful linguistic work that hides behind Trump’s natural and off the cuff style. Consider the following pair of tweets:

The students in my Cultural Studies of New Media course are currently in the process of giving midterm presentations. The assignment was to keep a technology journal for a week, interview a peer, and interview an older adult. Students were to record their own and others’ experiences with new and social media. Students then collaborated in small groups to pull out themes from their interviews and journals and created presentations addressing the role of new and social media in everyday life.

Across presentations, I’m noticing a fascinating trend in the ways that students and their interviewees talk about the relationship between themselves and their digital stuff– especially mobile phones. They talk about technologies that are “there for you,” and alternatively, recount those moments when the technology “lets you down.” Students recount jubilation and exasperation as they and their interviewees connect, search, lurk, post, and click.

Listening to students, I am reminded that the contemporary human relationship to hardware and software is a decidedly affective one. The way we talk about our devices drips with emotion—lust, frustration, hatred, and love. This strong emotional tenor toward technological objects brings me back to a classic Louis C.K. bit, in which the comedian describes expressions of vitriol toward mobile devices in the wake of communication delays. For Louis, the comedic value is found in the absurdity of such visceral animosity toward a communication medium, coupled with a lack of appreciation for the highly advanced technology that the medium employs. more...

From the beginning of his entrance into the race, we’ve been clamoring to categorize Trump, to understand where he fits into the political and cultural landscape. First, he was a flash in the pan, an inevitable “also ran” with whom voters would quickly lose interest. He’s an “outsider,” despite his bragging about pulling the strings of politics through political donations for decades. He’s a fascist, hell-bent on whipping up national fervor to undermine democratic institutions and further bolster white supremacist power. And, of course, he’s a troll just trying to get voters riled up.

At Nancy Reagan’s funeral presidential candidate Hillary Clinton told MSNBC that the Reagans “started a national conversation about AIDS.” The response to that obviously false statement was swift and loud. Even Chad Griffin, the president of the Human Rights Campaign (which endorsed Clinton), tweeted “Nancy Reagan was, sadly, no hero in the fight against HIV/AIDS.” Clinton’s apology was posted to Medium the very next day. Picking a platform for a message goes a long way in picking the demographics of your message’s audience. The decision to use Medium for her apology was pitch perfect: older (and statistically more conservative) voters who watch cable news will see her praising the Reagans while younger voters who might turn to Medium to read the definitive take down of Clinton will find her own apology next to their favorite authors. More than just an apology though, the post goes on to give a small history of AIDS-related activism before going on to describe the present challenges facing those infected with HIV. More than an apology Clinton’s Medium post is an example of what I’m calling the “Explainer Candidate.” more...

CW: Cissexism, genital mutilation, penis shaming

“You know what they say about men with small hands?”

—Marco Rubio

Shame and genitals go together like peanut butter and jelly. The story of Adam and Eve tells us just how enduring this shame is. With knowledge came shame, and their nakedness and the differences of their genitals started a downward spiral of fear—fear of our own genitals, and fear of others. From mutilation of the labia and clitoris, to castration, to the disturbing obsession with the state of transgender and nonbinary people’s genitals, we have been conditioned to judge, manipulate, and even destroy these most sensitive body parts. And I really, really wish we would stop doing that. more...

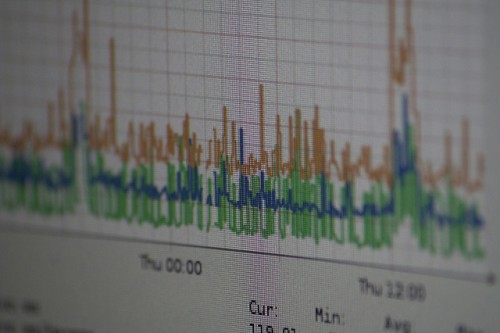

Horse-race style political opinion polling is an integral a part of western democratic elections, with a history dating back to the 1800’s. Political opinion polling originally took hold in the first quarter of the 19th century, when a Pennsylvania straw poll predicted Andrew Jackson’s victory over John Quincey Adams in the bid for President of the United States. The weekly magazine Literary Digest then began conducting national opinion polls in the early 1900s, followed finally by the representative sampling introduced the George Gallup in 1936. Gallup’s polling method is the foundation of political opinion polls to this day (even though the Gallup poll itself recently retired from presidential election predictions).

While polling has been around a long time, new technological developments let pollsters gather data more frequently, analyze and broadcast it more quickly, and project the data to wider audiences. Through these developments, polling data have moved to the center of election coverage. Major news outlets report on the polls as a compulsory part of political segments, candidates cite poll numbers in their speeches and interviews, and tickers scroll poll numbers across both social media feeds and the bottom of television screens. So central has polling become that in-the-moment polling data superimpose candidates as they participate in televised debates, creating media events in which performance and analysis converge in real time. So integral has polling become to the election process that it may be difficult to imagine what coverage would look in the absence of these widely projected metrics. more...

I’ve dedicated a few essays to interrogating encryption and automation as a replacement for human judgement, politics, and inter-personal trust. Central to that argument is the observation that the replacement of institutions with technologies like blockchains are a rehashing of the arguments that set up those failing institutions in the first place. (You can read the full argument here and here.)

I’ve dedicated a few essays to interrogating encryption and automation as a replacement for human judgement, politics, and inter-personal trust. Central to that argument is the observation that the replacement of institutions with technologies like blockchains are a rehashing of the arguments that set up those failing institutions in the first place. (You can read the full argument here and here.)

This is important because the problems with have with our present institutions –how they are exploitable, alienating, or otherwise broken– may very well be exacerbated by these technologies, not solved by them. To drive this point home I have pulled a few excerpts from Max Weber’s writing on bureaucracy but I have replaced a few nouns (in bold) so that his references to human organizations are replaced by algorithms, blockchains, and other technologies. With just these few noun changes a 19th century German sociologist of modern statecraft turns into the next great TED talk:

An algorithm offers above all the optimum possibility for carrying through the principle of specializing administrative functions according to purely objective considerations. Individual tasks are allocated to heuristicfunctions who have specialized training and who by constant practice learn more and more. The ‘objective’ discharge of business primarily means a discharge of business according to calculable rules and ‘without regard for persons.’

Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of the files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs– these are raised to the optimum point with blockchain technology.

The tendency toward secrecy in certain development communities follows their material nature: everywhere that the power interests of the domination structure toward the outside are at stake, whether it is an economic competition of a private enterprise, or a foreign, potentially hostile polity, we find secrecy.

The absolute monarch is powerless opposite the superior knowledge of the crowd–in a certain sense more powerless than any other political head.

And here are the originals:

Bureaucratization offers above all the optimum possibility for carrying through the principle of specializing administrative functions according to purely objective considerations. Individual performances are allocated to functionaries who have specialized training and who by constant practice learn more and more. The ‘objective’ discharge of business primarily means a discharge of business according to calculable rules and ‘without regard for persons.’

Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of the files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs– these are raised to the optimum point in the strictly bureaucratic administration, and especially in its monocratic form.

The tendency toward secrecy in certain administrative fields follows their material nature: everywhere that the power interests of the domination structure toward the outside are at stake, whether it is an economic competition of a private enterprise, or a foreign, potentially hostile polity, we find secrecy.

The absolute monarch is powerless opposite the superior knowledge of the bureaucratic expert–in a certain sense more powerless than any other political head.

Facebook Reactions don’t grant expressive freedom, they tighten the platform’s affective control.

Facebook Reactions don’t grant expressive freedom, they tighten the platform’s affective control.

The range of human emotion is both vast and deep. We are tortured, elated, and ambivalent; we are bored and antsy and enthralled; we project and introspect and seek solace and seek solitude. Emotions are heavy, except when they’re light. So complex is human affect that artists and poets make careers attempting to capture the allusive sentiments that drive us, incapacitate us, bring us together, and tear us apart. Popular communication media are charged with the overwhelming task of facilitating the expression of human emotion, by humans who are so often unsure how they should—or even do—feel. For a long time, Facebook handled this with a “Like” button.

Last week, the Facebook team finally expanded the available emotional repertoire available to users. “Reactions,” as Facebook calls them, include not only “Like,” but also “Love,” “Haha,” “Wow,” “Sad,” and “Angry.” The “Like” option is still signified by a version of the iconic blue thumbs-up, while the other Reactions are signified by yellow emoji faces.

Ostensibly, Facebook’s Reactions give users the opportunity to more adequately respond to others, given the desire to do so with only the effort of a single click. The available Reaction categories are derived from the most common one-word comments people left on their friends’ posts, combined with sentiments users commonly expressed through “stickers.” At a glance, this looks like greater expressive capacity for users, rooted in the sentimental expressions of users themselves. And this is exactly how Facebook bills the change—it captures the range of users’ emotions and gives those emotions back to users as expressive tools.

However, the notion of greater expressive capacity through the Facebook platform is not only illusory, but masks the way that Reactions actually strengthen Facebook’s affective control. more...

In December 2015, the Democratic Party’s data infrastructure became the subject of fierce controversy. When it was publicly revealed that staffers of Bernie Sanders’s presidential bid breached rival Hillary Clinton’s voter data stored in NGP VAN’s VoteBuilder, this infrastructure, normally hidden from view, suddenly became a contested matter of concern. As the Democratic Party closed access to VoteBuilder for a period of time for the Sanders campaign, the candidate’s supporters, competitors to NGP VAN, and journalists publicly debated why the party had such control over voter data and, ultimately, the dangers that such centralization might pose for the party and the democratic process. I have spent the past decade studying platforms such as VoteBuilder. While the incident with Sanders raised a number of important issues, the Democratic Party’s data infrastructure, developed in the wake of the 2004 presidential election cycle, is a key reason for its well-documented technological advantages over its Republican rival that persisted at least through the 2014 midterm elections.

Before I go any further it is worth providing some background context from news reports on the Sanders data breach, with the caveat that I have no direct knowledge of and have not conducted original research on the incident. From journalistic reports, the basic facts behind the Sanders data breach of NGP VAN’s firewalls between campaigns seem clear enough. By exploiting a vulnerability in the NGP VAN system, staffers on the Sanders campaign pulled multiple lists of voters from the Clinton campaign’s voter data. According to news articles, this included data on things such as strong Clinton supporters in Iowa and New Hampshire, 24 lists in all. The DNC responded by temporarily suspending the Sanders campaign’s access to VoteBuilder, in effect preventing staffers from using their voter data less than two months out from the Iowa caucuses. more...

Donald Trump’s Twitter account is a huge part of his presidential campaign (Huge). The media quotes from it, his opponents try to score political points by making fun of it, and his fans / supporters constantly engage with its content. @realDonaldTrump is just that: a string of pronouncements that feel very (perhaps even a little too) real. As Britney Summit-Gil wrote back in December: “the beauty of Trump’s tweetability is that his fans don’t really care if he’s manicured or carefully crafted—it’s what they love about him. His tweets read just like his speeches sound. They’re off the cuff, natural, and engaging.”

I want to take a minute to dive into the powerful linguistic work that hides behind Trump’s natural and off the cuff style. Consider the following pair of tweets: