In the United States, the media often portrays marginalized groups through tropes and stereotypes, but these depictions rarely represent the diversity inherent in any group. A recent article in Slate demonstrates that queer parents are no exception. The author draws on sociological work to examine how the gay-parenting community may reinforce this uniform image of gay parents in their social circles.

Sociologist Suzanna Walters argues that the gay community has limited its own image, members, and freedom in exchange for social acceptance. In her book, she explains,

“Media evinces a form of homophobia…focusing on acceptance of gay parents as heterosexual clones,” — in particular, the “ideal heterosexual”(white, upper-middle class, etc.). Parents who didn’t fit a certain mold were sidelined to present a comforting image to straight society.”

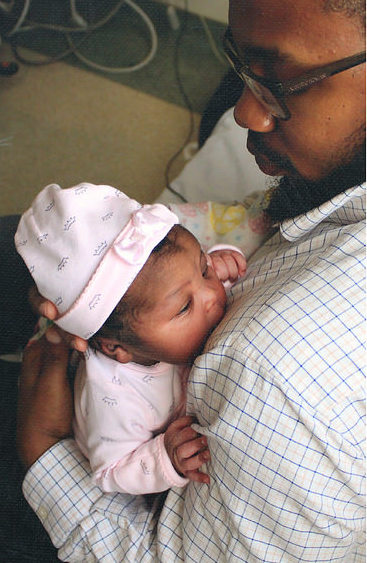

Megan Carroll noticed a similar pattern after attending gay parent groups in Texas, California, and Utah. Carroll noticed that fathers of color were severely underrepresented in these groups, and many parents of color told Carroll they felt “isolated” and without a space to “help their children connect to their race as well as their father’s sexuality.”

Gay dads with kids from previous heterosexual marriages faced a similar feeling of “otherness.” Gay dads by divorce were perceived as “relics of a bygone era,” while adoption or surrogacy were viewed as modern forms of parenting. Even groups that advertised themselves as being inclusive often fell short, including a group in Texas. Carroll remembers,

“when you showed up in person, the community was very insular towards adoption and surrogacy dads.”

Parenting groups and resources are an important tool for any caregiver, and as Carroll’s work outlines, parenting communities need to consider how to make these spaces more inclusive for all types of parents. She concludes,

“Segregation of gay fathers by pathway to parenthood is not an accident…It’s very much rooted in these networks fostered within the gay parenting community. If we’re not creating resources specifically for gay fathers from different backgrounds…it’s very unlikely they’re going to benefit from the resources already in place.”