Many parents worry that college will introduce their kids to a realm of unmediated romps between the sheets, but for all the very public discussions about “hooking up,” the trend of unceremonious sex didn’t start with this generation. Despite common portrayals of unchecked, excessive sexuality on university campuses, the Millennial generation isn’t having more casual sex than the Baby Boomers did in their time. In an online article for Cosmopolitan Magazine, Charlotte Lieberman turns to sociology to explain why modern college romance (or the lack thereof) is “so screwed up.”

Lieberman draws from Michael Kimmel’s Guyland, which argues that our society rewards those who follow the “rules” of masculinity and show “no fears, no doubts, and no vulnerabilities.” This type of emotional detachment has become a common defense mechanism in the dating world, says Lieberman, as women are often applauded for taking on attitudes typical of men.

Most of my peers would say ‘You go, girl’ to a young woman who is career-focused, athletically competitive, or interested in casual sex.

Some feminists have viewed casual sex as an example of women’s liberation, as the freedom to break gender norms and act more masculine. However, according to sociologist Lisa Wade, this “freedom” doesn’t go both ways.

[No one says] “You go, boy!” when a guy feels liberated enough to learn to knit, decide to be a stay-at-home dad, or learn ballet.

According to both Kimmel and Wade, our culture celebrates “thick skin” and emotional detachment in sexuality, rather than the transgression of gender norms. Hookup culture has created a dating field with a “whoever-cares-less-wins” attitude.

With emoticons and emojis replacing emotions, another complication of modern-day dating, according to Lieberman, is modern-day technology. Text messaging has become a main form of communication, and Millennials have developed self-screening skills that model Kimmel’s rules of emotional distance.

[When responding to a guy’s text,] it can’t be 10 minutes on the dot, because then it is obvious you were waiting. It should be longer than 15 minutes to show you’re not desperate but within the 45-minute window if you are trying to lay groundwork for that evening.

What is “screwed up” about dating, according to Lieberman and sociologists, is not that this generation has become emotionally desensitized by casual sex, but that Millennials are looking for love in the midst of a culture that views emotional apathy as empowering and possesses the digital means to censor any emotions they may experience.

![]()

![]()

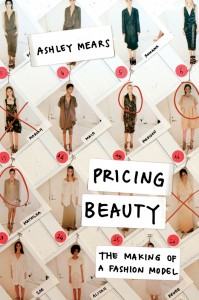

d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent

d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent