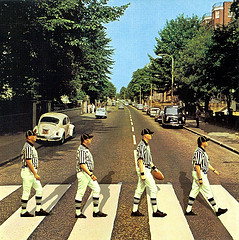

The Twitterverse and blogosphere exploded after NFL replacement referees blew a call on Monday Night Football, costing the Green Bay Packers a victory. Even President Obama piped up on Tuesday, encouraging a swift end to the labor dispute between the NFL and its regular referees. Michael Hiltzik of the Los Angeles Times agrees that we should all be paying attention to the unfolding drama, but argues that we might be missing the point:

Most news coverage of this labor dispute focuses on the ineptitude of the fill-in referees; this week there will be a lot of hand-wringing over the flagrantly bad call that turned a Green Bay interception into a game-winning Seattle touchdown, as if by alchemy. Occasionally you’ll read that the disagreement has something to do with retirement pay. But it’s really about much more.

It’s about employers’ assault on the very concept of retirement security. It’s about employers’ willingness to resort to strong-arm tactics with workers, because they believe that in today’s environment unions can be pushed around (they’re not wrong). You ignore this labor dispute at your peril, because the same treatment is waiting for you.

One issue at the heart of the conflict is the NFL’s goal to end the referees’ pension plan and move to a 401(k)-style plan, which Hiltzik notes is not unique among U.S. employers.

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell has argued that defined-benefit plans are a thing of the past — even he doesn’t have one, he told an interviewer recently, as though financially he’s in the same boat as any other league employee.

This is as pure an expression as you’ll find of the race to the bottom in corporate treatment of employees. Industry’s shift from defined-benefit retirement plans to 401(k) plans has helped to destroy retirement security for millions of Americans by shifting pension risk from employer to employee, exposing the latter to financial market meltdowns like those that occurred in 2000 and 2008.

It’s true that employers coast-to-coast have tried to put a bullet in the heart of the defined-benefit plan. The union representing 45,000 Verizon workers gave up on such coverage for new employees to settle a 15-month contract dispute.

But why anyone should sympathize with the desire of the NFL, one of the most successful business enterprises in history, to do so, much less admire its efforts, isn’t so clear. If you have one of these disappearing retirement plans today, don’t be surprised to hear your employer lament, “even the NFL can’t afford them” tomorrow.

Another common trend is an increase in the use of lockouts as a means of resolving labor disputes.

Lockouts have become more widespread generally: A recent survey by Bloomberg BNA found that as a percentage of U.S. work stoppages, lockouts had increased to 8.07% last year, the highest ratio on record, from less than 3% in 1991. In other words, work stoppages of all kinds have declined by 75% in that period — but more of them are initiated by employers.

The reasons are obvious. “Lockouts put pressure on the employees because nobody can collect a paycheck,” said William B. Gould IV, a former attorney for the National Labor Relations Board and a professor emeritus at Stanford Law School. “In a lot of major disputes, particularly in sports, it’s the weapon du jour.” Think about that the next time someone tells you that unions have too much power.

While the spotlight is sure to remain on the ire of fans and players alike toward the botched calls by replacement refs, America’s Game may be showing us more about business as usual in the United States than we would like to see.

It’s been said that football simply replicates the rough and tumble of the real world, and in this case, sadly, the observation is too true.