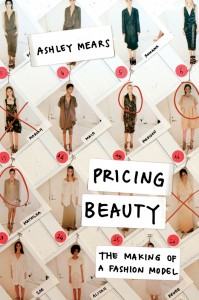

If you’ d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent New York Times’ T Magazine Blog interview with Mears got into what the world of fashion looks like through the eyes of and insider and the eyes of a sociologist.

d spent some time in the New York fashion scene and looked closely among the high heels, you might have spotted one model taking scrupulous field notes as seriously as she took the runway. Ashley Mears, assistant professor of sociology at Boston University and author of the book Pricing Beauty, immersed herself into the world of modeling by actually becoming a model. A recent New York Times’ T Magazine Blog interview with Mears got into what the world of fashion looks like through the eyes of and insider and the eyes of a sociologist.

Mears didn’t specifically set out to study fashion models, she claims: “Rather, I study questions of how cultural value gets translated into economic values.” In fact, she had only some limited teenaged experience in the field, and so it was a surprise when a “career” in modeling more or less fell into her lap—she was approached as she puzzled over her dissertation topic at a Starbucks.

From her life backstage, Mears was able to draw several conclusions on a lingering disconnect between traditional beauty and the type of look often revered on the catwalk. First and foremost, she says, fashion makes a distinction between mass appeal and cultural prestige:

The commercial end… [does the] kinds of jobs that are intended to sell things, to move merchandise. They have to resonate with a mass audience. The editorial end is the elite end, it’s by far the more prestigious end … And they look really strange. They don’t resonate with a mass audience, and that’s the point. They’re not intended to. That’s kind of a general principle that we take from the art world. The more people a specific piece of art is intended to make sense to, the less valuable on the whole it is.

And why do the elite modeling specifications require an extraordinarily tall, extraordinarily thin, white woman? For Mears, it all stems from class:

If you look at a historical trajectory of what, in Western society, elite culture values, it’s this prized aesthetic for women with extremely thin, taut, controlled bodies. A corpulent body, a body with rolls and with flesh, is a body that signals looseness, sexual availability, and is antithetical to a kind of “elite” body. You can see this in strip clubs as well. There’s some ethnographic work that shows that strip clubs that cater to higher-class audiences have thinner women, and whiter women. You see it reproduce in all kinds of different settings.

Whether in boxing clubs or factories or catwalks, sociologists have a rich history of this kind of embedded ethnography. To read more about Mears’s research, visit her Boston University website here or pick up a copy of her book.

Comments