This article is reprinted, with author and publication permission, from September/October 2022 issue of The Criminologist.

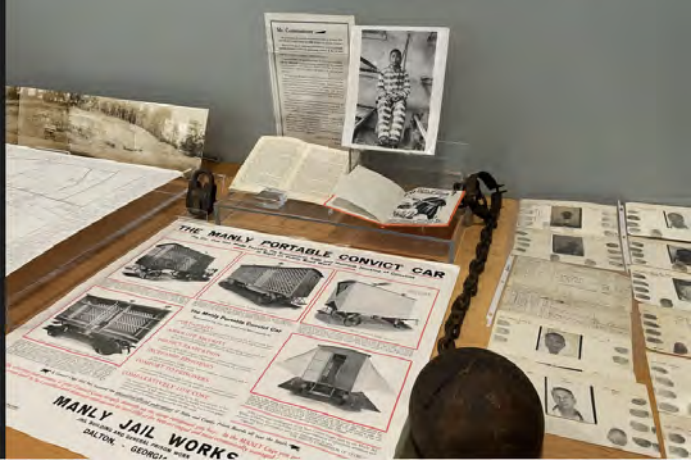

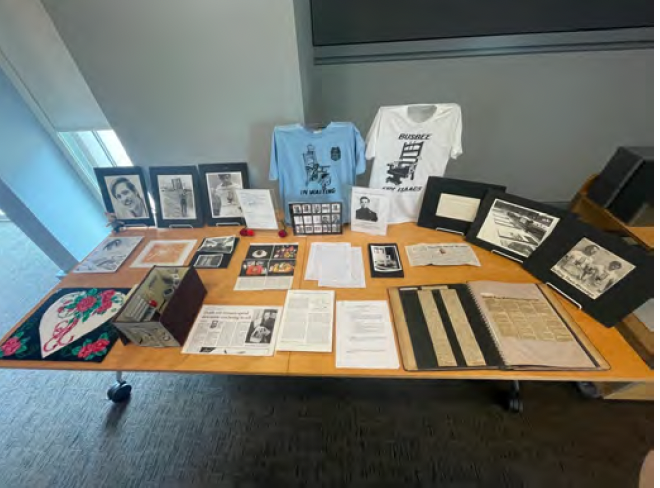

I wasn’t sure anyone would show up. My students had worked for six weeks to prepare a pop-up exhibit event showcasing their archival research projects on Georgia’s carceral history. In groups of four or five, my 44 students in Criminal Punishment & Society at the University of Georgia (UGA) prepared eight exhibits that told multi-layered stories of incarceration, convict leasing, probation/parole, fines and fees, boot camps, and life on death row spanning the late 19th to the early 21st centuries. The students worked in collaboration with university archivists to cull through multiple collections housed at the UGA Special Collections Library. They located and interpreted archival documents and objects, including media, and carefully crafted overview and caption texts to help visitors engage with big questions about how and why people have been punished by Georgia’s carceral state. During our final exam period for spring semester 2022 we set up our tables, put out our signage in the hallway of the UGA Special Collections Library, and crossed our fingers that at least some of the friends, colleagues, and community members we’d invited would come.

And they did. About 30 minutes into our event I scanned the room and smiled. I saw my students interacting enthusiastically with diverse members of our university and local communities. Guests included faculty and students, of course, but also the former head of our local public defender’s office, our county’s current district attorney, a former probation officer from New York, a friend of mine who spend 25 years locked up in Georgia prisons, and many others, including local activists involved in bail reform efforts and death penalty abolition. One attendee was delighted to see that an exhibit featured a letter he’d written decades ago as part of criminal justice reform efforts in southwest Georgia. My students left their final exam period feeling accomplished and wowed by the conversations they’d had about their work and guests’ real-world experience with their topics. All told, it was one of the most fulfilling teaching experiences of my career. In this article, I describe and reflect on my initial experiences implementing archives-based learning in undergraduate courses focused on criminal justice topics.

What is archives-based learning?

I designed this course after participating in UGA’s Special Collections Library Faculty Fellows Program that provides instructors with supported exploration of archives-based learning as a high impact learning practice. As a fellow, I collaborated with UGA archivists with the aim of including an archives-focused approach to the pedagogy and course design of a new or existing course. The program builds on the work of TeachArchives.org, a resource born of a three-year partnership between archivists and faculty in Brooklyn, New York to pioneer an approach to teaching in the archives. There are many models for incorporating archival materials into the classroom, including one-time encounters and semester-long engagement. Teaching with the archives includes directed, hands-on activities based on specific learning objectives, thoughtful selection of documents/objects, and small group activities. It is considered a high-impact educational practice because it teaches research skills, creates a common intellectual experience, and requires collaboration.

My approach to archives-based learning in two courses

So far, I’ve implemented archives-based learning in two of my courses: Juvenile Delinquency and Criminal Punishment and Society. Both are upper-division undergraduate elective courses, largely comprised of sociology and criminal justice majors. In Juvenile Delinquency, we visited the Special Collections Library twice during the semester, once near the beginning of the term and once later on. In the first encounter, students were assigned to groups and examined sets of archival documents and media clips that relate to the early juvenile court in Georgia from 1908 to the 1950s. Example documents included one of 100 original copies of a 1908 bill to establish juvenile courts in Georgia and a 1939 report describing subsequent reforms. I drew media clips largely from newsreel footage from the 1950s, including judges discussing juvenile court practices, youth sharing their experiences in juvenile training schools, and parents encouraging more community involvement in preventing delinquency. For the second visit, I curated several sets of documents and media clips from the “get tough” era of the 1980s and 1990s. Topics included boot camps touted by Georgia Governor Zell Miller in the 1990s, a movement to raise the age for the death penalty in Georgia to 18, and the 1998 settlement agreement between the state of Georgia and the Department of Justice to address suboptimal conditions in Georgia’s Youth Development Centers. Example media clips for the second visit included a segment of a documentary on boot camps and a two-part investigation by an Atlanta news station about Youth Development Centers. To assess students’ learning, I assigned reflection essays following each encounter that prompted students to articulate connections between the archival materials they worked with and course content (e.g., readings, class discussions, etc.). For Criminal Punishment and Society I used a much more intensive model. For the final six weeks of the semester, I moved all class meetings to the UGA Special Collections Library. I curated eight sets of archival documents, objects, and media clips that related to Georgia’s carceral history from the late 19th to early 21st century. Students were assigned to groups of four or five to work together on creating a pop-up exhibit. Unlike the two-encounter model I used for Juvenile Delinquency, students were required to search for additional archival materials beyond those that I provided. Students were guided by archivists in searching the archives as well writing captions and overview text for their exhibits. To chronicle and reflect on their learning throughout the project, students were responsible for writing blog posts describing their work as it unfolded over the six weeks. Their efforts culminated in the popup exhibit event that I described in the introduction to this article. Regardless of the model, implementing archives-based learning requires a great deal of preparatory work. From my experience, the process of locating, evaluating, and selecting archival materials for each course required many hours in the archives reading room. I enjoyed the research process a great deal, yet in both cases it took more time that I had anticipated. Of course, now that I’ve done this work once it will be far easier to implement future iterations of these courses with little additional time on the front-end. It’s also important to prepare students for encountering difficult language and topics in archival materials, especially in courses related to crime and criminal justice. For example, students in my courses regularly grappled with offensive language pertaining to race and sexual identity. I not only gave “trigger warnings,” but also provided space for students to take breaks or to discuss their reactions to offensive material in class, individually with me or one of the archivists, and in their writing, depending on how they felt most comfortable.

Impact on student learning and community engagement

Themes from my students’ reflection essays in both courses mirror findings from evaluations of the TeachingArchives.org project: working hands-on with the archives can be “revelatory,” working in small groups generates camaraderie, and intensive interaction with archival materials makes course content more relevant. Students in my courses remarked on how the visceral experience of touching archival objects and documents, as well as hearing and seeing first-hand accounts in archival media clips, brought course concepts to life for them in powerful ways. Students expressed that working with primary sources allowed them to apply course material to the real life events and people that generated the documents, objects, and clips they handled. Students also indicated that engaging with archival materials helped them understand and contemplate the historical context of our present moment more fully, especially in comprehending how policies related to criminal punishment and juvenile justice are developed, implemented, critiqued, and experienced by real people over time. Most notably, students in my Criminal Punishment and Society course indicated that working so intensively in small groups to create their exhibits helped them appreciate the value of group work for the first time. More than one student remarked that this course was the best group project experience they have had in college. Multiple students expressed that they made real friendships in their groups; for some this was the first time they had made friends through a college course. Many students stated that the small group work helped them consider others’ points of view on the same material and appreciate the benefits of learning with and from their peers.

Closing thoughts

My experiences in implementing archives-based learning have been fulfilling and I highly recommend this approach. It is timeintensive on the front-end, but there are a variety of formats that can fit just about any course, from one-time events to full semester engagement. TeachArchives.org is a wonderful resource with example exercises that can be adapted. Students have overwhelmingly endorsed it as a highly impactful learning experience. And, as our public pop-up exhibit event showed, archives-based learning can engage the broader campus and community in vital conversations about our shared past, present, and possibilities for change.

About the Author

Sarah Shannon’s research focuses on systems of criminal punishment and their effects on social life. Her interdisciplinary research has been published in top journals in several fields including sociology, criminology, public health, social work, and geography.

Sarah is also an award-winning teacher, having received recognition for excellence in undergraduate instruction, research mentoring, creative teaching, and service-learning. She proudly facilitates UGA’s first-ever Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program course in partnership with the Clarke County Jail.

As a publicly engaged scholar, Sarah’s research has been cited in several high profile media outlets including The New York Times, The Economist, and the Washington Post. Prior to her graduate work, Sarah worked in the non-profit sector. As a result, she cares about doing research that matters for academics, policy makers, and ordinary citizens.