How are borders made? State borders are the product of political conflict, nationalist discourse, unequal economic systems, and, as this essay shows, significant public financial investment. Public policy and political narratives naturalize state borders, often hiding how their origins are arbitrary and violent. State borders often mark space following war and conflict, but they also perform additional social functions like maintaining distinct political systems and differentiating between insiders and outsiders. Borders also construct economic difference by maintaining unequal trade relations, national currencies, and disparate value regimes across states and regional zones.

States create borders by dedicating public funds to construct and uphold them. In the post-9/11 United States, state officials juxtaposed the discourse of anti-terrorism with that of border regulation, contributing to the securitization of the US-Mexico border. President George W. Bush’s administration founded the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) through the Homeland Security Act of 2002. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) are two key agencies under DHS, responsible for apprehending, detaining, and deporting immigrants. CBP touts itself as “one of the world’s largest law enforcement organizations” (CBP, 2020) and states that its primary mission is “to detect and prevent the illegal entry of individuals into the United States” and “maintain borders that work” (CBP, 2021). ICE states that its “mission is to protect America from the cross-border crime and illegal immigration that threaten national security and public safety” (ICE, 2022).

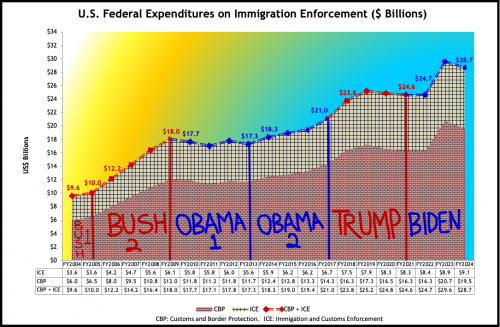

The chart above illustrates trends in federal spending on immigration enforcement and border security in the image of a fenced border wall (these figures are not adjusted for inflation). The brick wall represents the annual budget of CBP. The fence above the brick wall represents the annual budget of ICE. Graffitied sections of the wall represent the six presidential terms since 2002, namely, Bush 1, Bush 2, Obama 1, Obama 2, Trump, and Biden. The red and blue barbed wire represents the sum of annual budgets for CBP and ICE. Red sections of the barbed wire indicate budgets approved by Republican presidents, while blue sections indicate budgets approved by Democratic presidents. Numeric labels above the barbed wire represent the combined budget for CBP and ICE at the beginning and end of each presidential term.

Democratic and Republican presidents have expressed rhetorical differences in immigration policy, with Democrats articulating a more pro-immigrant stance compared to their Republican counterparts. The chart above gives the lie to the political performativity of partisan differences on immigration policy. In practice, Democratic presidents appear no less enthusiastic than their Republican counterparts in funding the border policing. In a period of 21 years, Democratic and Republican governments have spent a staggering total of $409.4 billion of public funds on immigration enforcement. $178.9 billion has been spent by Republican Presidents, averaging to $17.9 billion annually. $230.5 billion has been spent by Democratic Presidents, averaging to $21.0 billion annually. In total, $275 billion has been spent on CBP and $134.4 has been spent on ICE. Overall, federal expenditures on immigration enforcement have nearly tripled from $9.6 billion (FY2004) to $28.7 billion (FY2024) in unadjusted dollars. Adjusting for inflation to 2024 dollars still suggests an increase from about $17.5 billion to $28.7 billion.

When it comes to immigration, Republicans put their money where their mouth is, while Democrats do not. What explains this? The contrast between the partisan difference in immigration rhetoric and partisan consensus on immigration policy is rooted in the fundamental contradictions of bourgeois liberal democracy. While elected representatives are supposed to represent the will of the working people, in actuality they represent the interests of the ruling economic, political, and racial elite. Substantive progress towards de-carcerating the United States and de-securitizing the US-Mexico border might have been possible if progressives exercised greater power in Congress and if, in turn, Congress exercised greater power over the budget and immigration enforcement. In the current context, however, this is unlikely. In October 2023, President Joe Biden’s administration waived no fewer than 26 federal regulations to construct a border wall between the US and Mexico in Texas (Gonzalez, 2023), seemingly mimicking his Republican predecessor Donald Trump in advance of the 2024 presidential election. In the gaping void left by the abandonment of any commitment to a progressive ideological agenda in the Democratic Party, anti-immigrant violence fills the void.

Sources and Additional Reading

- Ackleson, J. (2005). Constructing security on the US–Mexico border. Political Geography, 24(2), 165-184.

- CBP 2020. Customs and Border Protection. 2020. “About CBP.” Washington, DC: Customs and Border Protection. Retrieved November 17, 2021 (https://www.cbp.gov/about)

- CBP 2021. Customs and Border Protection. 2021. “Border Patrol Overview.” Washington, DC: Customs and Border Protection. Retrieved November 17, 2021. (https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/along-us-borders/overview)

- Gonzalez, V. (2023, October 6). The Biden Administration says it is using executive power to allow border wall construction in Texas. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/border-wall-biden-immigration-texas-rio-grande-147d7ab497e6991e9ea929242f21ceb2

- ICE 2022. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. 2022. “Keeping America Safe.” Washington, DC: Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Retrieved November 17, 2021. (https://www.ice.gov/#)

- Reinke de Buitrago, S. (2017). The meaning of borders for national identity and state authority. Border politics: defining spaces of governance and forms of transgressions, 143-158.

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Budget in Brief Reports, FY2006 to FY2024, inclusive.

Dr. Ghazah Abbasi is a Postdoctoral Associate in Public Engagement at the Cornell Brooks School of Public Policy

Recently Nadya Tolokonnikova was

Recently Nadya Tolokonnikova was