Will Davies, a politics professor and economic sociologist at Goldsmiths, University of London, summarized his thoughts on Brexit for the Political Economy and Research Centre, arguing that the split wasn’t one of left and right, young and old, racist or not racist, but center and the periphery. You can read it in full there, or scroll down for my summary.

Will Davies, a politics professor and economic sociologist at Goldsmiths, University of London, summarized his thoughts on Brexit for the Political Economy and Research Centre, arguing that the split wasn’t one of left and right, young and old, racist or not racist, but center and the periphery. You can read it in full there, or scroll down for my summary.

——————————–

Many of the strongest advocates for Leave, many have noted, were actually among the beneficiaries of the UK’s relationship with the EU. Small towns and rural areas receive quite a bit of financial support. Those regions that voted for Leave in the greatest numbers, then, will also suffer some of the worst consequences of the Leave. What motivated to them to vote for a change that will in all likelihood make their lives worse?

Davies argues that the economic support they received from their relationship with the EU was paired with a culturally invisibility or active denigration by those in the center. Those in the periphery lived in a “shadow welfare state” alongside “a political culture which heaped scorn on dependency.”

Davies uses philosopher Nancy Fraser’s complementary ideas of recognition and redistribution: people need economic security (redistribution), but they need dignity, too (recognition). Malrecognition can be so psychically painful that even those who knew they would suffer economically may have been motivated to vote Leave. “Knowing that your business, farm, family or region is dependent on the beneficence of wealthy liberals,” writes Davies, “is unlikely to be a recipe for satisfaction.”

It was in this context that the political campaign for Leave penned the slogan: “Take back control.” In sociology we call this framing, a way of directing people to think about a situation not just as a problem, but a particular kind of problem. “Take back control” invokes the indignity of oppression. Davies explains:

It worked on every level between the macroeconomic and the psychoanalytic. Think of what it means on an individual level to rediscover control. To be a person without control (for instance to suffer incontinence or a facial tick) is to be the butt of cruel jokes, to be potentially embarrassed in public. It potentially reduces one’s independence. What was so clever about the language of the Leave campaign was that it spoke directly to this feeling of inadequacy and embarrassment, then promised to eradicate it. The promise had nothing to do with economics or policy, but everything to do with the psychological allure of autonomy and self-respect.

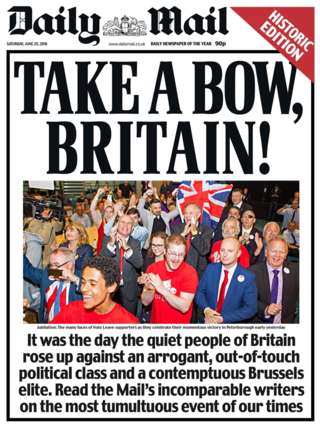

Consider the cover of the Daily Mail praising the decision and calling politicians “out-of-touch” and the EU “elite” and “contemptuous”:

From this point of view, Davies thinks that the reward wasn’t the Leave, but the vote itself, a veritable middle finger to the UK center and the EU “eurocrats.” They know their lives won’t get better after a Brexit, but they don’t see their lives getting any better under any circumstances, so they’ll take the opportunity to pop a symbolic middle finger. That’s all they think they have.

And that’s where Davies thinks the victory of the Leave vote parallels strongly with Donald Trump’s rise in the US:

Amongst people who have utterly given up on the future, political movements don’t need to promise any desirable and realistic change. If anything, they are more comforting and trustworthy if predicated on the notion that the future is beyond rescue, for that chimes more closely with people’s private experiences.

Some people believe that voting for Trump might in fact make things worse, but the pleasure of doing so — of popping a middle finger to the Republican party and political elites more generally — would be satisfaction enough. In this sense, they may be quite a lot like the Leavers. For the disenfranchised, a vote against pragmatism and solidarity may be the only satisfaction that this election, or others, is likely to get them.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 28

Noe Vencia — June 26, 2016

Thanks for bringing such a good article, Enjoyed both the summary and the original one.

The "popping a middle finger" theory is to really consider its relevance, specially on how easy is to do it in a EU vote, that it is seem as a distant matter. I highly doubt 52% are really about to ditch Labour and Tories to give the same message; too close to risk giving a simple message.

However, I still think the "finger" is of a lesser factor than the anti-immigrant one, both in UK and US. Talking on immigrants, I wonder why some countries have anti-immigrant parties (UK, France, Netherlands, Slovenia, Hungary, Poland...) while others has not (Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Greece, Denmark, Iceland...) Note that some of this last list have high unemployment while other have high levels of immigration!)

On Our Radar: Feminist News Roundup | Nudie News — June 27, 2016

[…] On the sociology of Brexit. [Sociological […]

Vivek Ydv — May 16, 2018

I am so glade to share this mahjongg titans free game, it is the most popular and addictive online played game. you don't miss this free opportunity and enjoy without download.

Mitchelll — December 4, 2018

plz send me lots of emails

famitofu — January 8, 2019

Broken smile, tired eyes. I can feel your longing heart

Call my name, basketball games from afar. I will bring a smile back !

Rayan — March 12, 2019

Many reasons; essay writer service has a single wide features spectrum and public sector unions exert enormous influence over news media.

Kris Santa Cruz — April 8, 2019

You can read about William Davies on wiki

factocert1 — October 2, 2019

This blog is so nice to me. I will continue to come here again and again. Visit my link as well. Good luck

mod apk — October 22, 2020

specially on how easy is to do it in a EU vote, that it is seem as a distant matter.

spotify premium apk — October 22, 2020

Take back control.” In sociology we call this framing, a way of directing people to think about a situation not just as a problem spotify apk premium, but a particular kind of problem

Johnson — November 27, 2020

yes

minilanomo — August 1, 2022

It sounds like he killed a tiger. However, that is not the case. He went to the Ussuri Reserve, which is where they are attempting to maintain a tiger population. The beast can be seen geometry dash dozing off in the well-known photograph. If it turned out that Putin had actually killed the animal in question, the Russian people would be furious.

Paula Marshall — September 27, 2022

Nice and interesting post. Thank You! For sharing such a great article. If you can't access your account and imagine you forgot your password and you don't know what to do then I know one blog about the poppy playtime and get back to your account.

pha medpros — October 20, 2022

While most of your day will be spent exploring, our cruises also offer plenty of time to relax in our historic private villas and boutique luxury hotels. Our blend of elegance and authenticity creates a wellness travel experience that is equal parts indulgence and cultural immersion.

ees login — October 25, 2022

Problem 5. If you have encountered any CAC enabled websites that have been working, recently stop working, please try adjusting your DNS. Some people are receiving an error message similar to this: "The DNS server might be having problems. Error Code: INET_E_RESOURCE_NOT_FOUND"

blooket join — October 29, 2022

Welcome to the world of Blooket! Learning is awesome, and that's why we built a tool to give it the excitement it deserves.

Employee KYC Update — November 23, 2022

EPF account link is a mandatory requirement for all EPF account holders.The account is merged with the Aadhaar card, PAN card, bank account, and other legal documents. The EPFO, the employee governing body, Employee KYC Update provides employees access to the UAN EPFO website portal. This helps employees update their KYC information and check other EPF related details. Updating KYC offers various benefits from low TDS on withdrawal, easy and fast way to operate your account, and keeps your banking details secure.

sara jane — June 26, 2023

Thank you for producing such a fascinating essay on this subject. This has sparked a lot of thought in me, and I'm looking forward to reading more.

gacha life game

Kristi Mendoza — September 29, 2023

Ufone is a subsidiary of Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited (PTCL) and is part of the Etisalat Group, a multinational telecommunications conglomerate based in the United Arab Emirates.

source: Ufone Balance Check Karne Ka Tarika

WritePapers — August 30, 2024

If you're unsure about how to create a discussion board post or need some tips to improve your skills, this article is a must-read. It breaks down everything you need to know and offers practical advice. Check it out here: https://writepapers.com/blog/what-is-a-discussion-board-post. It's been really helpful for me!

Will K. Dawson — September 3, 2024

I really like Your website and article you given is amazing. I have leart alot from it. Meanwhile i want to introduce my self as well I have a website that provides cotton products in bulk.

Will K. Dawson — September 3, 2024

"I really like Your website and article you given is amazing. I have leart alot from it. Meanwhile i want to introduce my self as well I have a website that provides cotton products in bulk.

"

Will K. Dawson — September 9, 2024

Die niederländische Website ist wirklich großartig! Es bietet ein nahtloses Benutzererlebnis mit einem klaren, intuitiven Design. Der Inhalt ist reichhaltig, informativ und gut organisiert, sodass Sie leicht navigieren und genau das finden können, wonach Sie suchen. Ein Muss für jeden, der sich für niederländische Kultur, Produkte oder Dienstleistungen interessiert! Besuchen Sie.

Will K. Dawson — September 9, 2024

"Die niederländische Website ist wirklich großartig! Es bietet ein nahtloses Benutzererlebnis mit einem klaren, intuitiven Design. Der Inhalt ist reichhaltig, informativ und gut organisiert, sodass Sie leicht navigieren und genau das finden können, wonach Sie suchen. Ein Muss für jeden, der sich für niederländische Kultur, Produkte oder Dienstleistungen interessiert! Besuchen Sie https://deutschtime.de

"

Will K. Dawson — September 9, 2024

"Die niederländische Website ist wirklich großartig! Es bietet ein nahtloses Benutzererlebnis mit einem klaren, intuitiven Design. Der Inhalt ist reichhaltig, informativ und gut organisiert, sodass Sie leicht navigieren und genau das finden können, wonach Sie suchen. Ein Muss für jeden, der sich für niederländische Kultur, Produkte oder Dienstleistungen interessiert! Besuchen Sie https://deutschtime.de

limcypackaging — September 9, 2024

The sociology of Brexit reveals motivations like nationalism, economic concerns, and a desire for sovereignty. Many "Leave" voters were driven by feelings of lost control over immigration, dissatisfaction with the EU’s bureaucracy, and socio-economic inequalities. Cultural identity and anti-globalization sentiments also fueled the Brexit decision.

limcypackaging — September 12, 2024

The motivation behind the "Leave" vote in Brexit was driven by factors like nationalism, anti-immigration sentiments, economic concerns, and skepticism of the European Union's influence. Many voters felt that leaving the EU would restore UK sovereignty, control over borders, and better opportunities for local industries and workers.

Monica Wlemay — October 23, 2024

Dein Blog ist wirklich interessant! Schaut doch mal auf https://rykerwebb.de/, da gibt es auch spannende Inhalte.