Cross-posted at Jezebel.

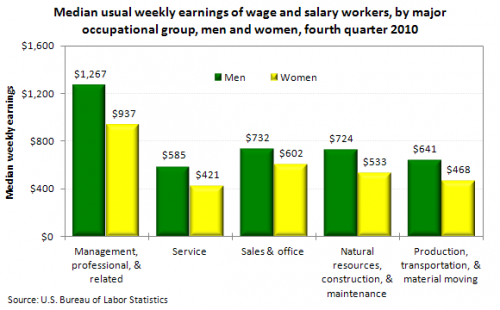

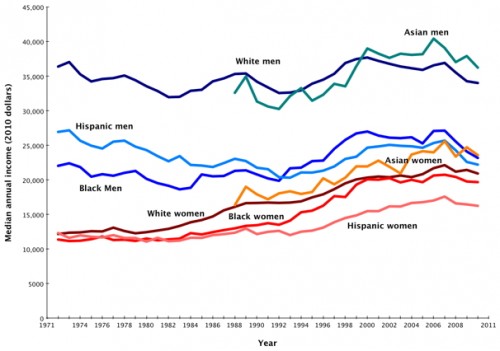

Kelsey C. sent in a graph from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that highlights the gender wage gap. Among full-time workers during the last three months of 2010, men made more per week than women in each of these occupational categories:

In terms of dollars, the gap is largest for the highest-paid workers — $330 — and smallest for those in sales/office, at $130. By percent, it’s worst for service (women make 72% as much as men in that sector) and again smallest for sales/office (women make 82% as much as men in that area).

And if we extrapolate this out, it adds up to a significant difference in annual earnings. If these income levels persisted for, say, 50 weeks, men in management would make $16,500 more than women; in sales, they’d make $6,500 more.

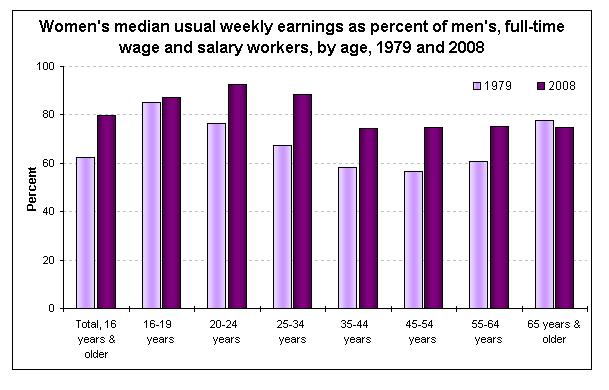

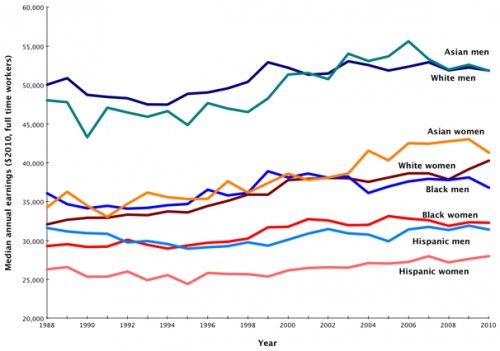

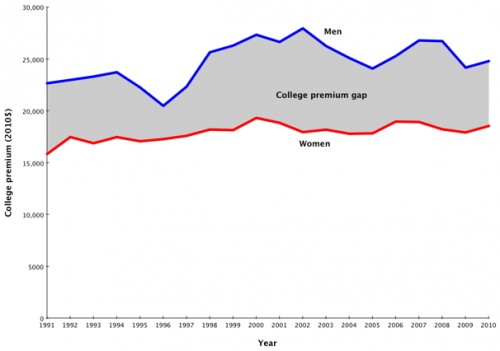

This is the only image the BLS provides, but if you’re interested in the topic, the full report has wages broken down by age and race/ethnicity (and sex within those categories) as well.