The humanities are in retreat. For years science and technology have been running roughshod over the arts in the nation’s colleges and universities, a thrashing turning now into rout.

This is hardly news. For years a consistent string of news articles and commentaries have documented the humanities’ decline. An especially robust burst of coverage greeted the release last summer of “The Heart of the Matter,” an earnest series of recommendations and equally earnest short film produced under the auspices of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Backed by a prestige-dripping commission of actors, journalists, musicians, directors, academics, jurists, executives and politicians, “The Heart of the Matter” sounded what the New York Times called a “rallying cry against the entrenched idea that the humanities and social sciences are luxuries that employment-minded students can ill afford.” In our race for results, the commission urged, the quest for meaning must never be abandoned.

Alas, the sad truth is that earnestness at this point doesn’t begin to cut it. Celebrity endorsements won’t reverse the trend, either. We may as well come clean and accept that the fact that the humanities have been losing this fight for centuries, and a reversal of their fortunes isn’t likely anytime soon.

The reason, I think, is fairly simple. Relative to the tangible solidities produced by science, technology, and capital, the gifts the humanities offer are ephemeral, and thus easily dismissed. “The basis of all authority,” said Alfred North Whitehead, “is the supremacy of fact over thought.”

This is not to say the humanities won’t retain a place at the table. They will, insofar as they can make themselves useful. But like Oliver Twist, the paucity of their portion will always leave them begging for more. All the more reason, then, to celebrate those who have managed to land a blow or two against the empire.

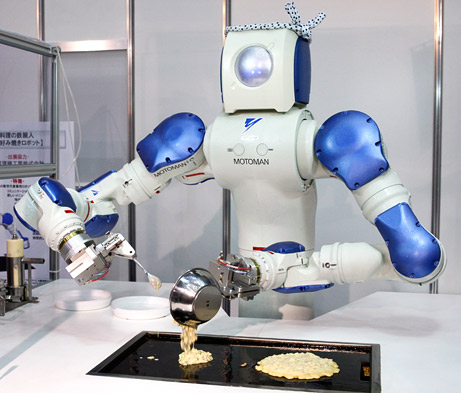

One of the early aggressors against whom the seekers of Higher Truth had to defend themselves was Francis Bacon. His introduction of the scientific method was accompanied by an unending string of attacks on the philosophers of ancient Greece for their worthless navel-gazing. Like children, he said, “they are prone to talking, and incapable of generation, their wisdom being loquacious and unproductive of effects.” The “real and legitimate goal of the sciences,” Bacon added, “is the endowment of human life with new inventions and riches.”

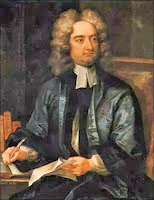

Legions of scientific wannabes followed Bacon’s lead to become dedicated experimental tinkerers in whatever the Enlightenment’s version of garages might have been. Meanwhile Jonathan Swift stood to one side and argued, with droll, often scatological amusement, that the emperor had no clothes.

Those who read Gulliver’s Travels in the days before literature classes were eliminated may recall Gulliver’s visits to the Academies of Balnibarbi (parodies of Salomon’s House, the utopian research center envisioned in Bacon’s New Atlantis), where scientists labored to produce sunshine from cucumbers and to reverse the process of digestion by turning human excrement into food. Embraced in greeting by the filth-encrusted investigator conducting the latter experiment, Gulliver remarked parenthetically that this had been “a Compliment I could well have excused.”

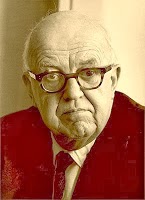

A more recent battle in what might be called the Arena of Empiricism unfolded in 1959, when C.P. Snow presented his famous lecture, “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.”

The cultures to which the title referred were those of literary intellectuals on the one hand and of scientists on the other. While it’s true Snow criticized the scientists for knowing little more of literature than Dickens, by far the bulk of his disdain was reserved for the intellectuals. Sounding a lot like Bacon, Snow said the scientists had “the future in their bones,” while the ranks of literature were filled with “natural Luddites” who “wished the future did not exist.”

Again, a partisan of the humanities launched a spirited counterattack, this one fueled not by satire but by undiluted rage.

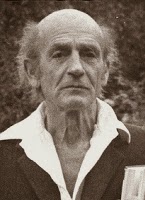

Manning the barricades was F. R. Leavis, a longtime professor of literature at Downing College, Cambridge. Leavis was well known in English intellectual circles as a staunch defender of the unsurpassed sublimity of the great authors, whom he saw as holding up an increasingly vital standard of excellence in the face of an onrushing tide of modern mediocrity. Snow’s lecture represented to Leavis the perfect embodiment of that mediocrity, and thus a clarion call to repel the barbarians at the gate.

From his opening paragraph Leavis’s attack was relentless. Snow’s lecture demonstrated “an utter lack of intellectual distinction and an embarrassing vulgarity of style,” its logic proceeding “with so extreme a naïveté of unconsciousness and irresponsibility that to call it a movement of thought is to flatter it.”

Snow, Leavis said, made the classic mistake of those who saw salvation in industrial progress: he equated wealth with well being. The results of such a belief were on display for all to see in modern America: “the energy, the triumphant technology, the productivity, the high standard of living and the life impoverishment—the human emptiness; emptiness and boredom craving alcohol—of one kind or another.”

The uncompromising spleen of Leavis’s tirade certainly outdid the conciliatory platitudes of the “The Heart of the Matter,” but to no greater effect. Neither fire and brimstone nor earnest entreaty will rescue the humanities from their fate. Meaning will remain the underdog in a world that increasingly demands the goods to which it has increasingly grown accustomed.

Defeatist? To the contrary, all the more reason to carry on the fight, boldly and without apology. I keep a quote from Jonathan Swift taped over my desk:

“When you think of the world give it one lash the more at my request. The chief end I propose in all my labors is to vex the world rather than divert it.”

Doug Hill’s book, Not So Fast: Thinking Twice About Technology, has just been published on Amazon Kindle and other outlets. He blogs at The Question Concerning Technology and can be followed on Twitter at @DougHill25.