Green grass with morning dew clinging and glowing in the sunlight. Image by Nandhu Kumar from Pexels is licensed under Pexels license.

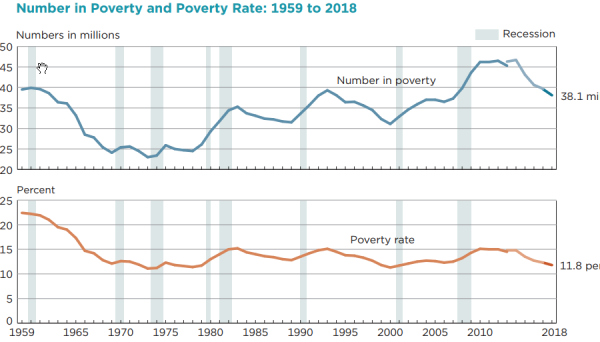

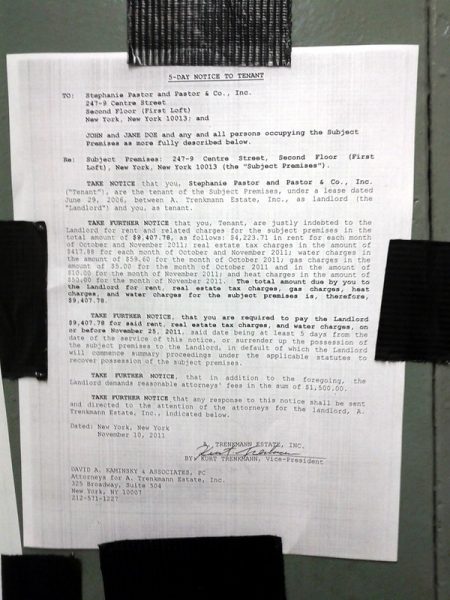

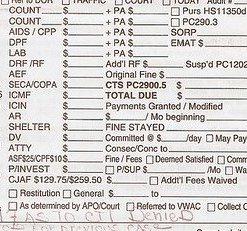

When a crime is committed, the harm done to victims and communities can rarely be healed by writing a check or locking someone up. Yet the U.S. criminal justice system’s approach relies heavily on fines and incarceration to punish those who have harmed others. These sanctions fall heaviest on those with the least ability to pay, particularly minoritized groups, leading to a domino effect of harm on individuals, families, and communities. Researchers have long criticized these responses as ineffective at best and, at worst, contributing to greater harm and recidivism. As a result, there have been calls for new approaches to justice.

- Karin D. Martin, Bryan L. Sykes, Sarah Shannon, Frank Edwards, and Alexes Harris. 2004. “Monetary Sanctions: Legal Financial Obligations in US Systems of Justice.” Annual Review of Criminology 1: 471-495.

- Veronica L. Horowitz, Ryan P. Larson, Robert Stewart & Christopher Uggen. 2024. “Fines, Fees, and Families: Monetary Sanctions As Stigmatized Intergenerational Exchange.” The Sociological Quarterly: 1-20.

- Charles Loeffler & Daniel Nagin. 2022. The Impact of Incarceration on Recidivism. Annual Review of Criminology, 5, 133-152.

What is Restorative Justice?

Restorative Justice (RJ) is an approach that operates alongside or in lieu of traditional criminal justice, as in school, workplace, and other settings as well. It encompasses a variety of practices, often derived from Indigenous cultural traditions, such as the “circle process” and “victim-offender conferencing.” Unlike the standard U.S. system, which views crime as a violation of the law against the government, RJ focuses on the harm caused to relationships. It does this by 1) empowering those harmed and the community to decide how to address the harm and 2) encouraging those responsible to face the affected individuals and take direct accountability, when appropriate.

RJ, in its reactive form, a trained facilitator organizes structured meetings between those involved in an incident to address and resolve the harm caused. Proactively, RJ can involve gatherings where people socialize and strengthen relationships – in the absence of a specific incident. Generally, RJ is used reactively and during these meetings three key questions are discussed: 1) What happened? 2) What have the impacts been? and 3) What can be done to make things better?

For instance, imagine a parent allowed their child to wait at the bus stop near their home. A neighbor’s German Shepherd, often left unsupervised, starts frequenting the area and one day bites the child. This incident sparks conflict between the dog’s owner and the concerned parent. A typical response might involve fining the dog owner and requiring them to keep the dog confined, which could escalate tensions in the neighborhood between dog lovers and concerned parents.

In contrast, a Restorative Justice (RJ) process would bring together the dog owner, the child and their parents, and other concerned neighbors to address the situation. Through open discussions, questions and different perspectives would be explored, allowing all parties to express their concerns and needs. This could lead to creative solutions, such as the dog owner agreeing to better supervision or installing a secure fence, while the community works together to ensure the safety of children at the bus stop by taking turns waiting with the children. Ultimately, this approach could not only resolve the issue but also foster a stronger sense of trust and cooperation within the neighborhood.

- Daniel Van Ness, Karen Heetderks, Jonathan Derby, & Lynette Parker. 2022. Restoring justice: An introduction to restorative justice. Routledge.

- Howard Zehr. The Little Book of Restorative Justice. 2015. Simon and Schuster.

- Mark Umbreit. Victim Meets Offender: The Impact of Restorative Justice and Mediation. 2023. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Edward Charles Valandra, ed. Colorizing restorative justice: Voicing our realities. Living Justice Press, 2020.

Does Restorative Justice Work?

For over 40 years, research assessing the effectiveness of RJ has consistently shown it to be a relatively better solution for a range of minor-to-serious crimes. First, people who participate in RJ instead of the traditional process (fines and jail) had significantly lower rates of repeating harm. Second, people who were harmed felt RJ was more inclusive to them than the traditional process, and those involved in more serious-incidents experienced lower rates of PTSD symptoms. Third and lastly, RJ was significantly cheaper than the court process and empowering to communities. Overall, RJ is a well-established, evidence-based practice that is growing a viable response to both property and violent crimes.

- James Bonta, Rebecca Jesseman, Tanya Rugge, Robert Cormier. 2005. Restorative Justice and Recidivism. In Handbook of Restorative Justice, pages 108-120. Routledge.

- Heather Strang, Lawrence W Sherman, Evan Mayo-Wilson, Daniel Woods, and Barak Ariel. 2013. Restorative Justice Conferencing (RJC) Using Face-to-Face Meetings of Offenders and Victims: Effects on Offender Recidivism and Victim Satisfaction. A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 9(1), 1-59.

- Lawrence W Sherman, Heather Strang, Evan Mayo-Wilson, Daniel Woods, and Barak Ariel. 2015. Are restorative justice conferences effective in reducing repeat offending? Findings from a Campbell systematic review. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 31, 1-24.

Restorative Justice is Growing.

There has been significant growth and adoption of RJ around the world, with the United States, Canada, The United Kingdom, Taiwan, Japan, Tanzania, Rwanda, South Africa, and over 80 other countries having formalized laws surrounding the use of RJ for crime. Notably, New Zealand has been a consistent pioneer in incorporating RJ, particularly in its youth justice system, which has influenced practices globally. In North America, RJ programs have gained traction in many states and provinces, often supported by legislative frameworks that encourage their use.

As RJ continues to gain recognition and support globally, it offers a promising alternative to traditional justice systems, emphasizing healing, accountability, and community cohesion over punishment through fines and incarceration. In doing so, the global RJ movement may ultimately encourage a shift towards more humane and effective ways of addressing harm and achieving true justice.

- Julena Jumbe Gabagambi. 2018. A comparative analysis of restorative justice practices in Africa. Hauser Global Law School Program.

- Daniel W. Van Ness. “An overview of restorative justice around the world.” (2016).

- Brunilda Pali & Giuseppe Maglione. Discursive representations of restorative justice in international policies.” European Journal of Criminology 20.2 (2023): 507-527.