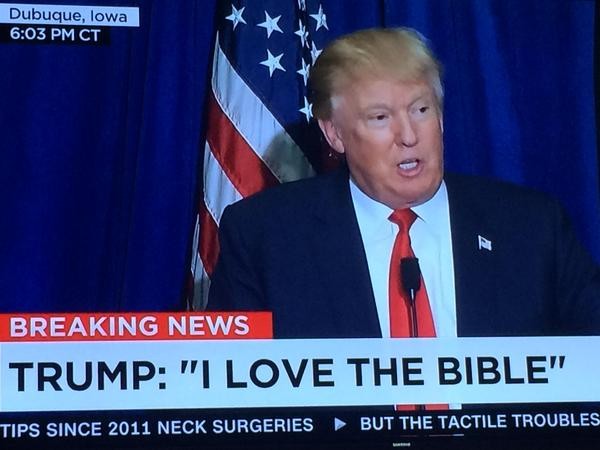

At this week’s Republican National Convention, Donald Trump will accept the party’s nomination for president. Social scientists explain Trump’s primary success by looking at his supporters, especially at their racial biases and class grievances. The nomination is still surprising, though, because Trump has managed to win reluctant support from party leaders, influence the GOP platform, and gain traction among Evangelical Christians (despite not seeming all that pious himself). Sociological research on political parties and organizing show how an unlikely leader can win institutional favor even when they seem to clash with the individuals who run the show.

How is Trump winning over party elites? We often think about political parties as groups of savvy leaders who design the system to keep themselves in office (and challengers out). A longstanding sociological take, however, shows how parties represent deep divisions in the public along race, class, and ideology. This means that emerging public interest groups can and do swing party politics, such as the Democrats’ shift toward a civil rights agenda or the rise of the Tea Party coalition among Republicans.

- Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan. 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York/London: Free Press/Collier-MacMillan

- Jeff Manza and Clem Brooks. 1999. Social Cleavages and Political Change: Voter Alignments and US Party Coalitions. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Stephanie L. Mudge and Anthony S. Chen. 2014. “Political Parties and the Sociological Imagination: Past, Present, and Future Directions,” Annual Review of Sociology 40(1):305–30

And how did a man quoting “Two Corinthians” win over leaders in the Religious Right? This group’s political influence doesn’t just come from the pulpit. Instead, shared beliefs allow lay leaders to build networks among influential people in government, business, and entertainment. Much of their success comes from “unobtrusive organizing”—the way the networks, in turn, work within existing power structures to acquire political influence. Thus, the Religious Right can fall in line with a candidate who does not seem to fit their public agenda if it means even more power and access behind the scenes.

- Michael Lindsay. 2008. Faith in the Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jaime Kucinskas. 2014. “,The Unobtrusive Tactics of Religious Movements,” Sociology of Religion 75(4):537–50.

- Lydia Bean. 2014. The Politics of Evangelical Identity: Local Churches and Partisan Divides in the United States and Canada. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.