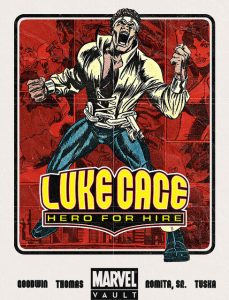

Marvel’s new series focusing on superhero Luke Cage debuted on Netflix in late September to critical acclaim. The show boasts a 95% rating on RottenTomatoes and was called “one of the most socially relevant and smartest shows on the small screen you will see this year,” by Deadline.com’s Dominic Patten. Aside from its artistic merits, commentaries also praise the prominence of Luke Cage as a “bulletproof black man in a hoodie,” with the show’s star Michael Colter telling The Huffington Post: “It’s a nod to Trayvon, no question … Trayvon Martin and people like him. People like Jordan Davis, a kid who was shot because of the perception that he was a danger. When you’re a black man in a hoodie all of a sudden you’re a criminal.”

Comic books and comic book culture have slowly become more diverse as companies like Marvel have begun prioritizing the inclusion of racial minorities in their stories. Kamala Khan, a Muslim teen, has replaced the white hero Carol Danvers as Ms. Marvel. The hero replacing Iron Man is a black teen named Riri Williams. And Miles Morales, a black Hispanic teen, replaced the white Peter Parker as Spider-Man. Yet despite its recent progressive slant, Marvel and other comic companies have had issues with racial stereotyping, particularly with their black heroes. Marc Singer describes how the medium of comics relies on racialized representations, with appearance being a major way to distinguish characters from one another.

- Marc Singer. 2002. “Black Skins” and White Masks: Comic Books and the Secret of Race.” African American Review 36(1), 107-119.

- Adilifu Nama. 2011. Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Super Heroes. University of Texas Press.

- Herman Gray. 2013. “Subject(ed) to Recognition.” American Quarterly (65:4), 771-798.

This is also heavily tied up in the portrayal of superheroes as super-masculine. When the racial aspect of this dynamic is uncovered, we see a complicated history. Rob Lendrum traces these heroes to the “blaxploitation” era of film/media in the 1970s, arguing that many superheroes were influenced by this culture, including Luke Cage. Jeffrey A. Brown sees these images as one-note and compares them to the black-owned works of Milestone Media Inc. comics.

- Jeffrey A. Brown. 1999. “Comic Book Masculinity and the New Black Superhero.” African American Review 33(1), 25-42.

- Rob Lendrum. 2005. “The Super Black Macho, One Baaad Mutha: Black Superhero Masculinity in 1970s Mainstream Comic Books.” Extrapolation 46(3), 360-372.